Thank you for helping us meet our fundraising goal!

Researchers from across Canada will collaborate on a vast clinical trial to study whether the plasma of recovered patients can be used to treat COVID-19.

The study, the largest to date ever done on the subject, will include about 50 Canadian institutions, including 15 in Quebec.

"It's a therapy to treat the illness," said one of the lead researchers, Dr. Philippe Begin of Montreal's CHU Ste-Justine hospital.

"We're talking about passive immunizations, while with a vaccine we're talking about active immunization."

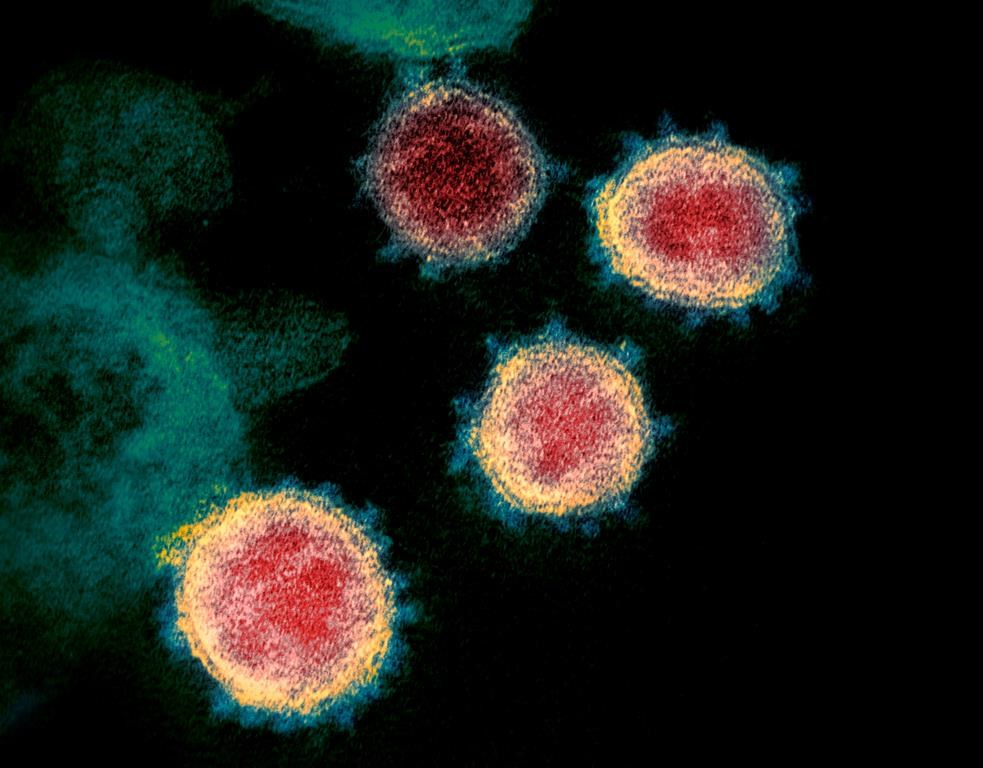

Passive immunization consists of transfusing plasma from patients who have recovered from COVID-19 — called convalescent plasma — to patients in the early stages of the illness in order to provide protective antibodies and hopefully limit the severity of symptoms.

Plasma is the liquid portion of the blood that contains the antibodies that protect against illness.

Begin cited the proverb, "Give a man a fish and feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and feed him for a lifetime." Teaching someone to fish, he said, would be the equivalent of a vaccine that prompts the body to make its own antibodies.

But with no vaccine available, convalescent plasma is the best alternative.

"But now we don't have time, because we don't yet know how to fish, so we can't really teach it," he said. "So the idea is that we just give the antibodies created by someone else."

The approach was used before the development of vaccines to combat epidemics, and it's not the first time the idea of using convalescent plasma has been raised in the fight against COVID-19. But thus far, the evidence in favour remains largely anecdotal and of poor scientific quality.

The study will include researchers from the Universite de Montreal, the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal, Hema-Quebec, McMaster University, and Sunnybrook and SickKids hospitals in Toronto, among others.

Begin admitted researchers are running "a little blind" when it comes to the use of plasma.

"We don't have a ton of studies that tell us, it takes this kind of antibody, or this amount of plasma," he said.

The best way to get answers is to assemble as much data as possible, as quickly as possible, he said.

"We want to go fast, and the best way to go fast is have several of us following the same protocol to put all the data together," he said.

"We have colleagues in other countries who are interested and with whom we share our protocols."

Plasma will be collected about a month after a patient recovers, when antibody levels are at their highest. COVID-19 was first reported in Quebec in late February, and the number of potential donors in the province remains low, although it's growing.

Therefore, the researchers have decided the convalescent plasma will be reserved for those who are suffering from the illness, although it's not out of the question that it could be offered later to at-risk groups, such as health-care workers, as a preventive measure.

The study is expected to last about three months and involve more than 1,000 patients.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 9, 2020

Comments

I hope they're doing basic genetic testing of both controls and treated patients, for the ACE- Del allele in the ACE gene locations that are relevant to inflammatory reactions. Otherwise there is a good possibility that results will be inconclusive, with some getting better and some getting worse.

Why not look into hydroxychloroquine?