Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Jacqueline Wilcox was five weeks from finishing her final-year clinical placement at Toronto General Hospital when she was told not to return after emergency restrictions were imposed to control the COVID-19 pandemic in mid-March.

A couple of weeks later, she was back working at the hospital, but much had changed.

“There’s always something to be done,” the 27-year-old respiratory therapy student said. “We’re managing more patients that are more acute and an illness that no one has ever dealt with before.”

While Wilcox previously rotated through stints monitoring and treating patients’ cardiopulmonary needs in wards, clinics and operating rooms as well as its intensive care units (ICU), she now works mostly overnight shifts in the ICU dedicated to COVID-19 patients.

Wilcox said that means she is helping do a lot of proning, or turning a patient over so they are face down, which has been found to improve the supply of oxygen in some COVID-19 patients.

“That’s something I had never done in my placement,” she said.

“The first couple of times I did it by myself were pretty high-stress,” she added. “It’s not very complicated, you’re just turning them over, but in terms of protecting the airway, that’s your responsibility and if there is a ventilator disconnect, that’s a situation where everybody in the room would be at risk of being exposed to the virus.”

She also said a lot more patients are coming to the unit in need of ECMO (or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), a process which removes blood from a patient who is not responding to ventilation to oxygenate it before returning it to the patient, while other tasks she had been trained to do were not happening.

“There will be a second learning curve once things go back to normal because we’re not doing a lot of procedures we would normally be doing,” she said, such as assisting surgeons in the insertion of tracheostomy tubes or taking part in bronchoscopy procedures, which have been de-prioritized.

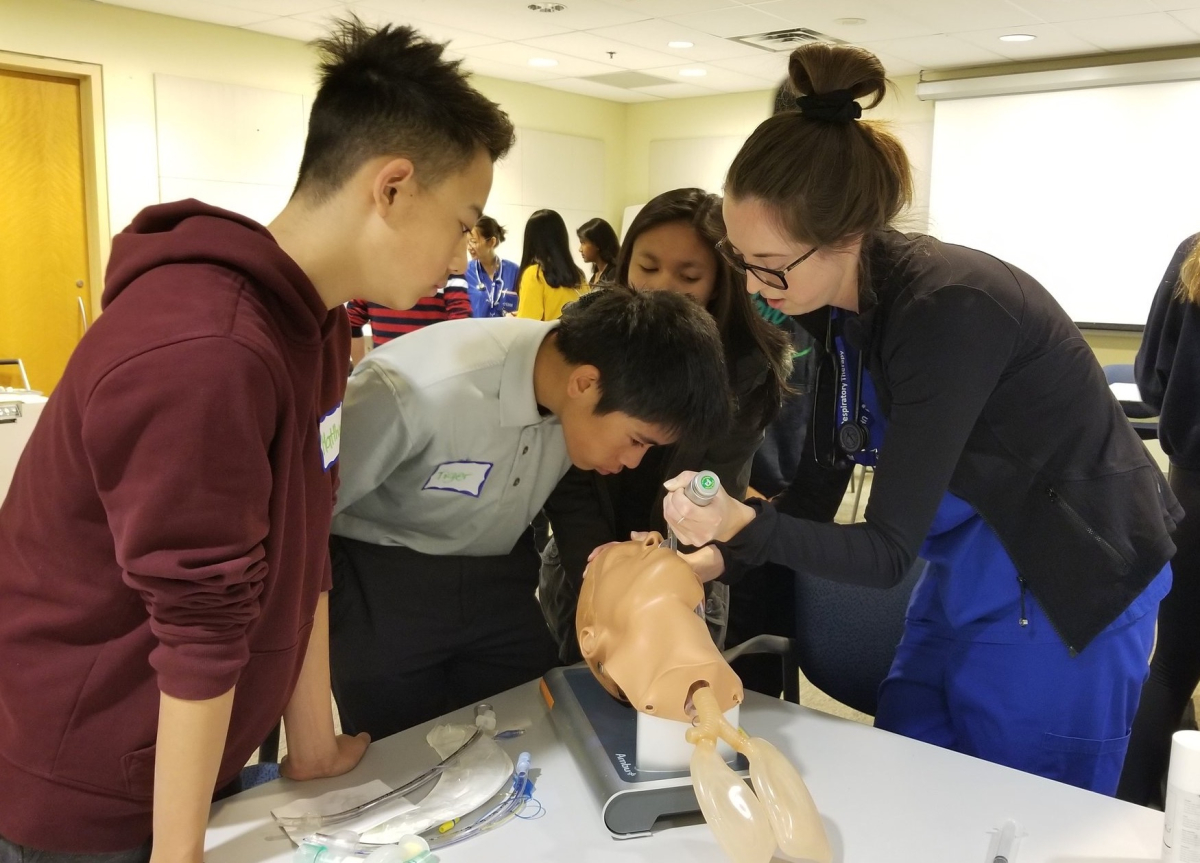

Wilcox is one of 30 students of the Michener Institute’s three-year diploma course in respiratory therapy, most of whom have been hired by its affiliated hospitals and put to work fighting COVID-19.

“We realized it would be very problematic for institutions if that class was not able to graduate,” said Dr. Brian Hodges, who is both UHN’s chief medical officer and its executive vice-president of education. “Intensive care units rely very heavily on respiratory therapists.”

So Hodges sought and received approvals from Ontario’s Ministry of Health and the College of Respiratory Therapists of Ontario that regulates RTs work to condense their final weeks of schooling.

“We explained that we wanted to not reduce anything in their qualifications, make sure that they had met all the competencies required and to allow them, despite the fact that COVID was hitting us, to complete the training and go quickly into the workforce,” he said.

“Fortunately, we don’t leave all of the clinical training to the very end,” he added.

Hodges said earlier this week that UHN was treating 80 COVID-19 patients on several wards.

‘Exciting, but surreal’

Jaspreet Singh got her call up to work in the intensive care unit at Toronto Western Hospital, another UHN site.

“It was exciting, but also surreal,” said Singh, another final-year respiratory therapy student. “We went from ending clinical early to becoming a front-line worker within days. As a new grad, you’re usually thinking about getting a job and passing the licensing exam, but instead we’re thinking about precautions in a pandemic.”

Wilcox said the board exam required for the students to be fully licensed was to take place in July, but has been pushed back at least until August.

A challenge for next year’s grads

Michener hasn’t halted its educational programming, instead switching mostly to virtual delivery, including for the 70 written exams across its programs that were due to take place recently.

But in-person interviews for next year’s intake of students have become video connections, while the school is also working on providing clinical skills training virtually.

That won’t be enough for those going into their final year, however, for whom the pandemic is creating another challenge: Students are unable to graduate without taking part in clinical placements, which are currently on hold until at least July 6.

“A real challenge for us is to create a full curriculum for all these health professionals next year, not knowing if the hospitals will allow students back in again or not,” Hodges said, noting that some 6,000 students are usually placed at UHN hospitals every year.

“Going into the fall, we're going to have to think about what can we open up in a safe way to allow for clinical experience,” he said, suggesting that parts of hospitals that are COVID-free could be opened.

Perhaps of some relief to those students, the provincial government on Thursday released a framework for hospitals to resume scheduled surgeries and procedures.

Alastair Sharp/Local Journalism Initiative/Canada's National Observer

Comments