Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Following a series of mishaps, northwest Saskatchewan community leaders want the province to revert to the region's original policy for COVID-19 security checkpoints.

The Northwest Communities Incident Command Centre is responsible for co-ordinating the COVID-19 response and co-operation between communities. The command centre includes representatives from the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan, First Nations and municipal governments.

Leaders say they were not consulted by the province in the process of implementing Saskatchewan's health order for the Northern Administration District.

“There’s only one incident command in the northwest region. The province has to work with us. The incident command has to be supported and respected, and we’re not getting that from the province,” incident commander Rick Laliberte told National Observer on Wednesday.

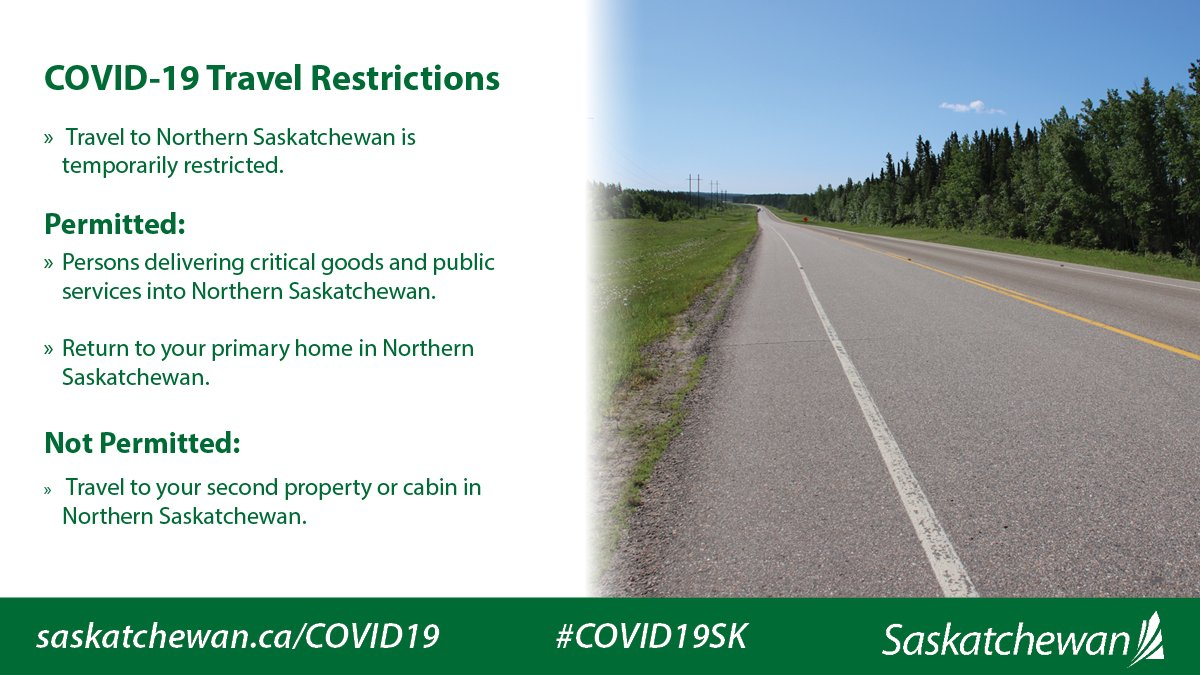

He wants the province to revert to its April 30 health order, which barred southerners, such as cabin owners, from traveling north, but not the other way around. That suited northerners just fine.

Laliberte said the confusion and conflict arising from the behaviour of out-of-town peace officers manning the checkpoints on behalf of the province has made it difficult for his team to focus on the task of containing the virus.

“They did the travel restrictions — which was fine — to support us. That's the April 30 health order. Then they changed that health order and they twisted it. The original health order said you could go out for essentials, food and medicine. The health order that’s in place now says that you can go out for medicine, but you have to get food from a neighbouring community,” Laliberte said.

“That totally counters what our strategy was. We were trying to lock down each community so that we don’t have inter-community travel.”

He said it’s preferable for people to buy groceries in Saskatoon or Prince Albert than in a neighbouring community because it reduces the risk of cross-contamination between northern communities.

Also, many needed items are not always available for purchase in the far north.

Communities had a protocol in place whereby leaders would write permission letters for people needing to get essentials, which he said worked well.

“They were writing contracts, waivers, for each member to leave with an agreement that when you come back, these are the protocols. Now we’re dealing with the province’s little twist,” he said.

Since May 8, Laliberte said, reports of issues at northern COVID-19 security checkpoints have flooded in from residents.

In one case, a medical taxi from Turner Lake went south with patients who bought groceries. Checkpoint authorities threatened them with a fine.

In another incident, Canoe Lake Cree First Nation Chief Francis Iron said he was denied access through a checkpoint on his way to Flying Dust First Nation.

“Our First Nation primary cheque signatory lives in Flying Dust and our families on social assistance and the First Nation payroll depend on those cheques and we need to pay our bills. These officers also have no regard of what an essential service for northerners is,” Iron said in a joint press release with the Meadow Lake Tribal Council, Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations and Métis Nation-Saskatchewan.

“He had to go sign social assistance cheques for people’s essential needs so they can purchase (items) and support themselves. The resource people wouldn’t let him through,” Laliberte said.

He said many checkpoint patrol officers are not from the area, don’t know the people, and generally come off as rude or being in a bad mood.

“We were willing to do the security checkpoints — we just didn’t have the authority. That’s what we’re being told. Unless you’re a peace officer — then you can block the roads for the health order. We were there as information checkpoints and that’s what we’re still doing. We still have the same authority. We asked for more authority, but they didn’t give it to us. Instead, they gave us people with authority and people with guns. People are upset at the checkpoints,” Laliberte said.

"We had the community containment under control. That’s a primary focus in our pandemic plan, and we had the regional perimeter to try to contain the oilsands infections. We’re informing the residents, we’re co-ordinating, we're managing the food delivery from the south, we’re disinfecting, we’re telling the people who are delivering how to conduct themselves with protocols."

He said that Saskatchewan Public Safety Agency officers and the provincial government aren't taking local residents or emergency response leaders seriously.

They’re treating us like kids, like we don’t know what we’re doing. We know exactly what we’re doing. We've been engaged since March 30. They’re the late people (who) came to join us. Their tactics are very colonial."

Laliberte sent a letter on March 8 to Dr. Saqib Shahab, Saskatchewan’s Chief Medical Health Officer, calling for clarity.

“This situation is unprecedented, and we appreciate the frustration and uncertainty you are facing. To leave us out — and not benefit from the knowledge we have, and the networks we understand — means you are facing even more uncertainty and frustration. We wish this to end,” Laliberte wrote.

The letter also cited confusion at Saskatchewan Public Safety Agency roadblock points and a “high level of variability” of “often incorrect” information shared at roadblock points.

Deputy Health Minister Max Hendricks responded on behalf of Shahab.

Hendricks said the Ministry of Health agrees that a successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic requires the collective efforts of all individuals and agencies.

“The Ministry of Health and Saskatchewan Health Authority will continue to work with all partners, including northern communities and First Nations and Métis governments, to protect all citizens from this global pandemic,” he said.

Hendricks said that while most of Saskatchewan is moving ahead with phases of reopening, the approach to reopening any community with an outbreak “must be considered carefully” and based on factors such as a downward trend in cases for two consistent weeks, adequate testing and contact tracing, and low risk of community transmission.

“We are by no means over this threat, but it is encouraging to see how quickly our collective efforts have had a meaningful and positive impact, as demonstrated by the recent epidemiological data showing a steady decline in new infections,” he said.

The Ministry of Government Relations and the Saskatchewan Public Safety Agency are expected to address the issues raised under their jurisdiction in separate letters to the Treaty Ten Pandemic Council.

For Laliberte, it’s about collaborating effectively, so that the needs of northwest residents are addressed.

“Here’s the important part. The process of us coming together is just as important as the plan. They have to be part of the process. They have to plug into us as decision makers,” he said.

“The north is united. We’ve seen these tactics done before by governments to break up community alliances up here, and that’s what’s happening in the midst of COVID-19. We want to work collectively, and they want to work apart.”

Michael Bramadat-Willcock/Local Journalism Initiative/Canada's National Observer

Comments