Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

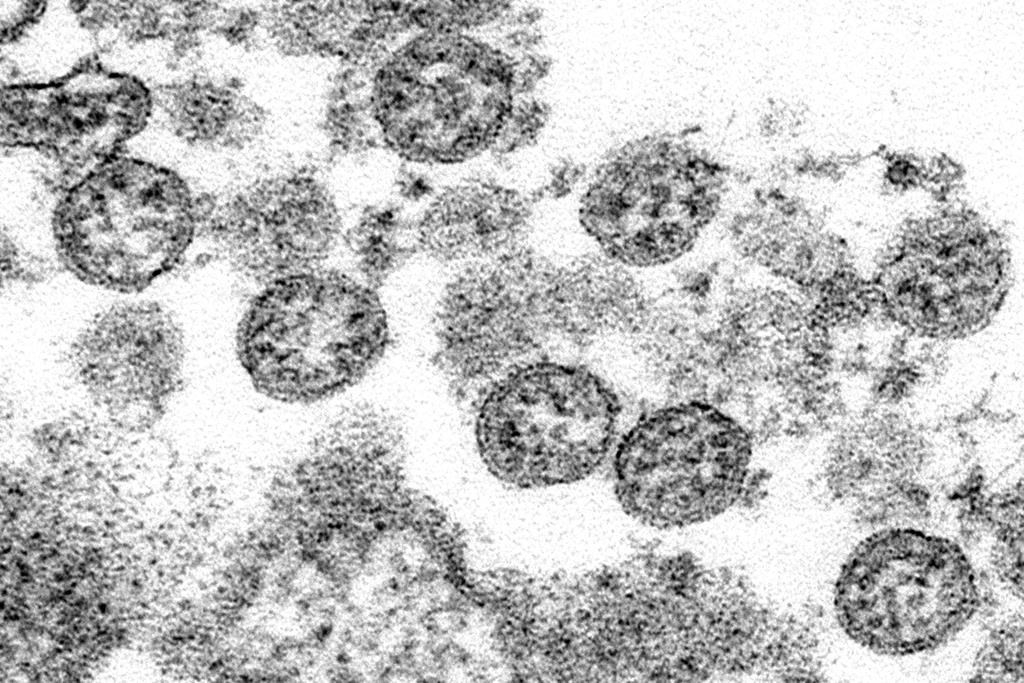

Montreal researchers have begun recruiting participants to test potential COVID-19 vaccines, a key step in the eventual production of a vaccine.

The Vaccine Study Centre at the McGill University Health Centre on Friday emailed out a request for research participants who wanted to be a part of future COVID-19 studies.

“These are difficult times and many of us who are not on the front lines feel that we could do more and want to help … being a participant in important clinical research for COVID-19 is one of them,” the email reads. “By signing up to receive information on future COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials, you are helping our MUHC researchers find a solution to stopping this deadly virus.”

The researchers encouraged recipients to share the email, hoping to gather a significant pool of potential candidates. They’re preparing for clinical studies, which will probably begin in late June or early July, according to Dr. Brian Ward, director of the centre.

Researchers are racing to produce a viable COVID-19 vaccine and many of them will be ready to test their candidate vaccines on humans in the summer, Ward said. The MUHC’s vaccine centre will be among those that will coordinate the testing of the vaccines.

The initial studies will only require several dozen people and can be completed in a few weeks, Ward said.

It will start with a phone call. A recruiter will screen willing participants to see if they meet the inclusion criteria. If they do, they will be invited to do some blood tests — to make sure they have no diseases they’re unaware of.

“Basically, you just need to be normal healthy to participate in these early studies,” Ward said.

Researchers will first test to see how much of the vaccine to give as a dose while monitoring the selected participants’ health and understanding if it prompts the desired immune system reaction. Full-scale testing of the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing COVID-19 will take more people and more time.

Similar trials have already taken place elsewhere. Ward is aware of six companies that are currently performing human trials of a COVID-19 vaccine. One American firm, Moderna, began trials in mid-march and has already reported promising results, but the company says that a vaccine suitable for the general public is still many months away.

By the summer, Ward expects about a dozen more players will be ready to test their candidate vaccines in humans. One such company, Medicago, is based in Quebec. In addition to his duties at the MUHC, Ward is the chief medical officer at Medicago. He described the small company as a “minnow” in the global pharmaceutical ocean, but he was optimistic about the early progress they have made toward a vaccine.

Evidence suggests humans gain no lasting immunity after they’ve been infected by any of the common coronaviruses that circulated before SARS-cov-2, Ward said, so a vaccine will probably be critical if society is to overcome the new virus.

But the existence of vaccines that work against COVID-19 will probably lead to division, Ward added, because even if the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies can produce hundreds of millions of doses, the supply will be insufficient to inoculate the world.

First responders and health-care workers are the obvious choices to be the first to receive a vaccine, Ward said, but once they receive it there will be contention as to who gets it next. The richest people, and the richest societies, will likely win that fight, Ward said, even though those who are poorest tend to be more gravely affected.

“In the United States, it’s really clear that it’s blacks and Hispanics who are getting creamed by this virus,” Ward said. “That’s because they don’t have the liberty to work from home. Is it going to be the African-American bus driver who gets the first dose of vaccine or is it going to be Donald Trump’s businessman buddy?”

Matthew Lapierre, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Gazette

Comments