Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Last week, deep within the bowels of the Federal Plaza, in a COVID-ravaged NYC, I stood in a half-empty hall, preparing to swear my oath of citizenship to the United States.

There were a few dozen of us, racially and religiously diverse immigrants, standing together yet apart, warily masked and socially distanced—the huddled masses yearning to breathe free, as we were once described in Emma Lazarus’ moving poem, affixed to the base of the Statue of Liberty. In front of us was a maroon dais, some empty chairs, a forlorn lectern, an artificial palm, and the Stars and Stripes flag, hanging limp and a little dusty.

We’d all been waiting to do this for months. Our ceremony had been abruptly ‘descheduled’ back in March after the USCIS offices, and just about everything else in NYC, closed down in a spastic and belated response to the killer pandemic.

The oath ceremony would be the last step before being granted citizenship, a goal I had been pursuing since getting a green card a few years back, just after the federal election of 2016. It’s no secret America has been spiralling into an abyss since then, and at times I felt like I was booking passage on the Titanic or jumping headlong into a garbage fire. Even at that time, the Lexington Avenue doctor I visited to get my required syphilis and TB screening expressed his incredulity.

“Why would you want to come here, when we’re all trying to figure how to get out?” he asked.

I wasn’t sure if he was joking. Now I think he probably wasn’t.

Born in Canada of German-citizen parents, I was already a bi-national. I’d come to the U.S. with my American-born wife, who had accepted an academic post here, and was living and working in NYC as a so-called ‘permanent resident.’

Yet ‘permanent,’ I was to find out, isn’t quite what it claims and, as with all green card holders, if ever I wanted to leave the U.S. for an extended period, I wouldn’t be automatically readmitted. Absence implies doubt, and America demands fealty. Also, permanent residents do not have the right to vote, and given that the ship of state is on fire and there will be a federal election in November, it seemed especially important to be casting my ballot. With a fascist in the Oval Office, many of my American loved ones were in the thick of the resistance, yet I felt myself keeping an ironic distance, hiding behind my non-citizenship. It was gradually dawning on me there was too much at stake to be stuck on the sidelines. So many of the people I cared about most in the world were here, and I needed to really be with them.

Earlier in the day, as I lined up outside the Federal Plaza building along with my fellow citizens-to-be, the air thick and the steel wool sky tormented by thunderstorms, and I reflected once again on what I was about to do. I thought about how broken and disorganized everything is here in America, so grimy, so corrupted — yet filled with the hope I saw in the faces of those waiting around me, standing there, in anticipation of this life-changing event. They were dressed in their Sunday best, nervously checking their phones and shuffling their feet, ducking from time to time beneath the insubstantial overhang of the adjoining building in a futile attempt to dodge the fat raindrops that still intermittently pelted down.

The lack of basic shelter from the elements for a bunch of random immigrants, waiting for a government service, came as no surprise to any of us. This was America, after all. The casual cruelty of neglected public infrastructure is apparent everywhere, from the overflowing airport toilets to the broken elevators and dearth of escalators in NYC subway stations, a brutal impediment to the old, the weak or the heavily burdened. There are individual stains on the tiles of stations that I recognize from the 1980s, when I first rode those subways, and I pass the time waiting for trains making little phone movies of rats on the tracks as they tussle over wrappers. You get used to it, really you do, and endure it with a kind of gallows humour, at least on a good day. In America, you are pretty much on your own, except for your friends and loved ones. These are the people you rely on. They are why I was here.

Yet, (and this is such a paradox), New York City can feel so incredibly welcoming. A city of immigrants, so many of us have come from somewhere else to try and make a go of it. We share our stories with each other, adapt to the chaos and unite in a sense of wonder. The city is like nowhere else on Earth, the good parts and the bad.

At Federal Plaza, anxious new arrivals hurried in from Worth Street. The gruff white security guard with a Staten Island accent barked at them, admonishing them not to stand at the checkpoint until their appointed time. His facemask hung below his nose, “Don’t worry, I don’t have COVID!” he joked, with the amiable brutality of white privilege in uniform as he rifled through their handbags and knapsacks, exhaling only inches away from their wincing eyes. By contrast, his co-workers, all of them people of colour, properly masked and gloved, were polite and helpful. Yet somehow the white guy got to be the person in charge, or at least he was acting like it. At night, just a few blocks away, the Black Lives Matter protests raged in the streets, and the shops were boarded up all down Broadway.

A couple of weeks earlier I had started getting what seemed like random calls from numbers with no caller I.D., which of course I ignored, but one morning, out of idle curiosity, I picked up. The caller was female. Her voice was barely audible and sounded like she was calling from her car, which for all I know she was.

“This is the USCIS calling. Is your birthday September 13th, 1959?”

“Yes”

Click…

The line went dead. That was it for another week or so.

While out for a run, I saw another ‘no caller I.D.’ flash across my phone screen. I picked up, and this time the kindly, Spanish-inflected voice of a different woman said she was calling from the USCIS office and had been trying to reach me.

“Was I still six feet tall?” she asked.

“Yes, I was,” I assured her, although lately I had been slouching terribly as the result of trying to conduct my life in front of the computer screen. But this was likely about to change. Under the COVID ‘Screen New Deal,’ my usual teaching assignments and associated health insurance were no longer assured, due to the anticipated collapse in college enrolment as doubt spreads over the value of American higher education, delivered online for full tuition. The USCIS, too, is suffering from under-enrolment; as would-be immigrants lose faith in the American brand, the agency, which is funded primarily by the high processing fees it charges for visas and residency permits, is nearing bankruptcy.

“Could I attend an oath ceremony in two weeks’ time?”

“Yes, I could,” I replied.

“But,” she quickly cautioned, “by the time we finish talking, the time slot may no longer be available due to problems with the ‘system.’”

“The system?” I replied.

“Yes. The system,” she answered without elaborating. “I’ll call you back.”

Click…

Amazingly, a few minutes later, she did call back and confirmed the date and time.

The wheels had been thrown into motion, and three weeks later, I found myself, finally, inside the ceremonially reduced halls of 26 Federal Plaza. As I pushed my green card toward the USCIS clerk, who sat behind a makeshift screen of Saran wrap (did she have to bring that from home?) I felt something shift inside. I was sorry, so very sorry for America, sorry for its failures, sorry for its pervasive inequality, sorry for its economic system founded on slavery and the continued immiseration of its workers, sorry there was no public health care or any other kind of viable social safety net, sorry for the murderous insanity of the gun rights movement, the general barbarism of the place, sorry for the whole careening broken mess to which I was about to swear allegiance formally and permanently. But it was my mess now too, no longer something from which I could stand apart.

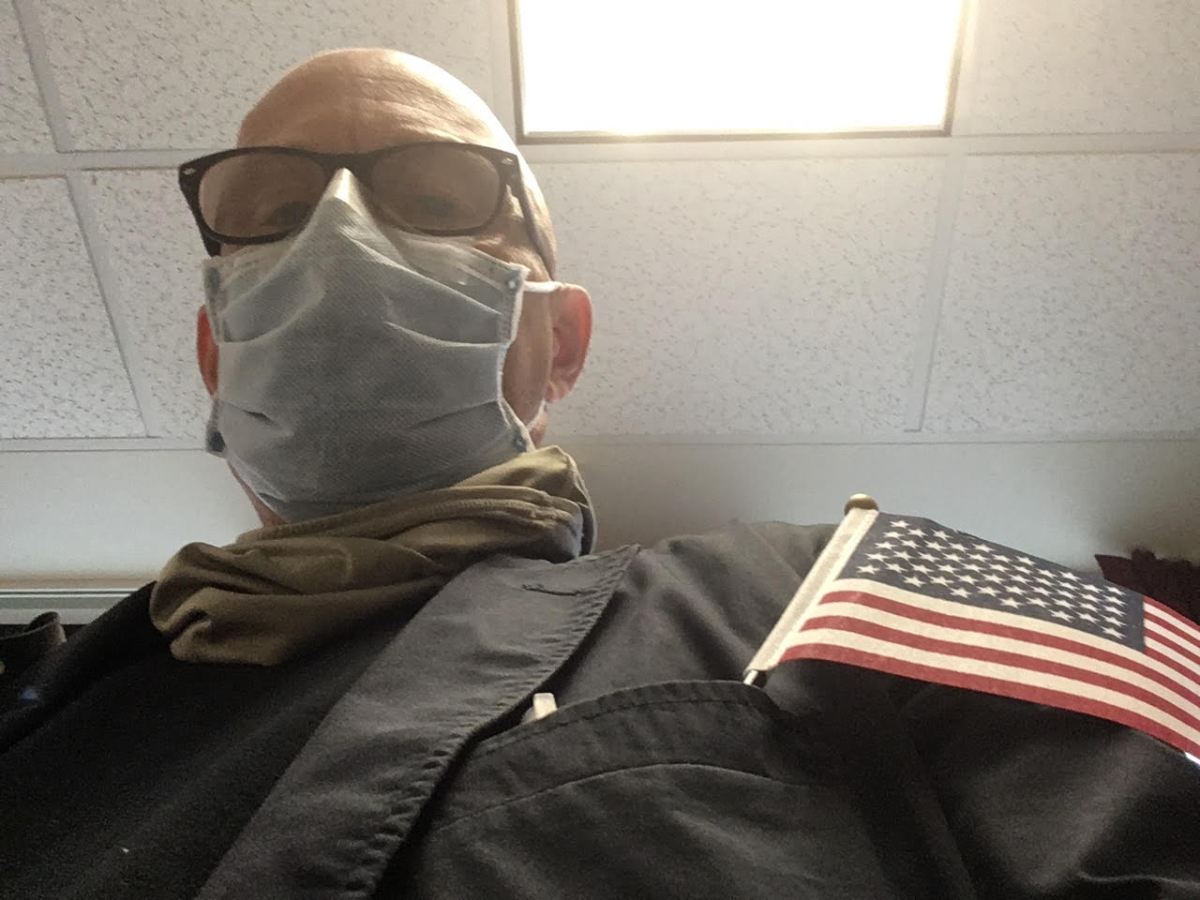

The clerk slid the envelope containing my certificate of citizenship, the text of the oath and a little American flag toward me, cautioning me not to sign the certificate until I had finished swearing. I headed to my assigned six-foot square on the linoleum and stood by with the others. The swearing, such as it was, was perfunctory, in keeping with the abbreviated nature of all social interactions in these viral times. Together we repeated the archaic vow as it was read out by a masked woman at the lectern. We declared absolutely and entirely to renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince or potentate, to support and defend the Constitution and the Laws of the United States (and a lot of other stuff); so help (us) God.

And then, after all the anticipation, it was over. We had all passed the portal into citizenship in this bastard child of the Enlightenment. We made our way out, past some velvet ropes and barricades, heading toward the down escalator (it worked), clutching our little Stars and Stripes. A guard congratulated each of us as we passed by. He seemed sincere, warm even. My face was oozing sweat under my tight-fitting mask and my nose was itching. I pushed through the revolving doors and transited from the institutional dimness into the now intense light of a post-thunderstorm July afternoon.

Outside the streets were steaming. Through Lower Manhattan, Chinatown and the Lower East Side, it would take me a while to walk back home.

Comments

So now, you can run for office!!!

Congratulations! New York, and all America is indeed a wonderful place. I'm a Canadian who thinks my country is lucky to have America as its neighbour.

I hope that both our countries can become closer to the ideals of freedom, fairness and opportunity that their populations dream of.

I look forward to your future comments.

". . . America is indeed a wonderful place." Heavens to Murgatroyd.

America is a wonderful place. You just need perspective and to stop listening to partisan hacks from either side. You are free to fight the oligarchs and support the values important to you. That's important in this current geography.

Condolences.