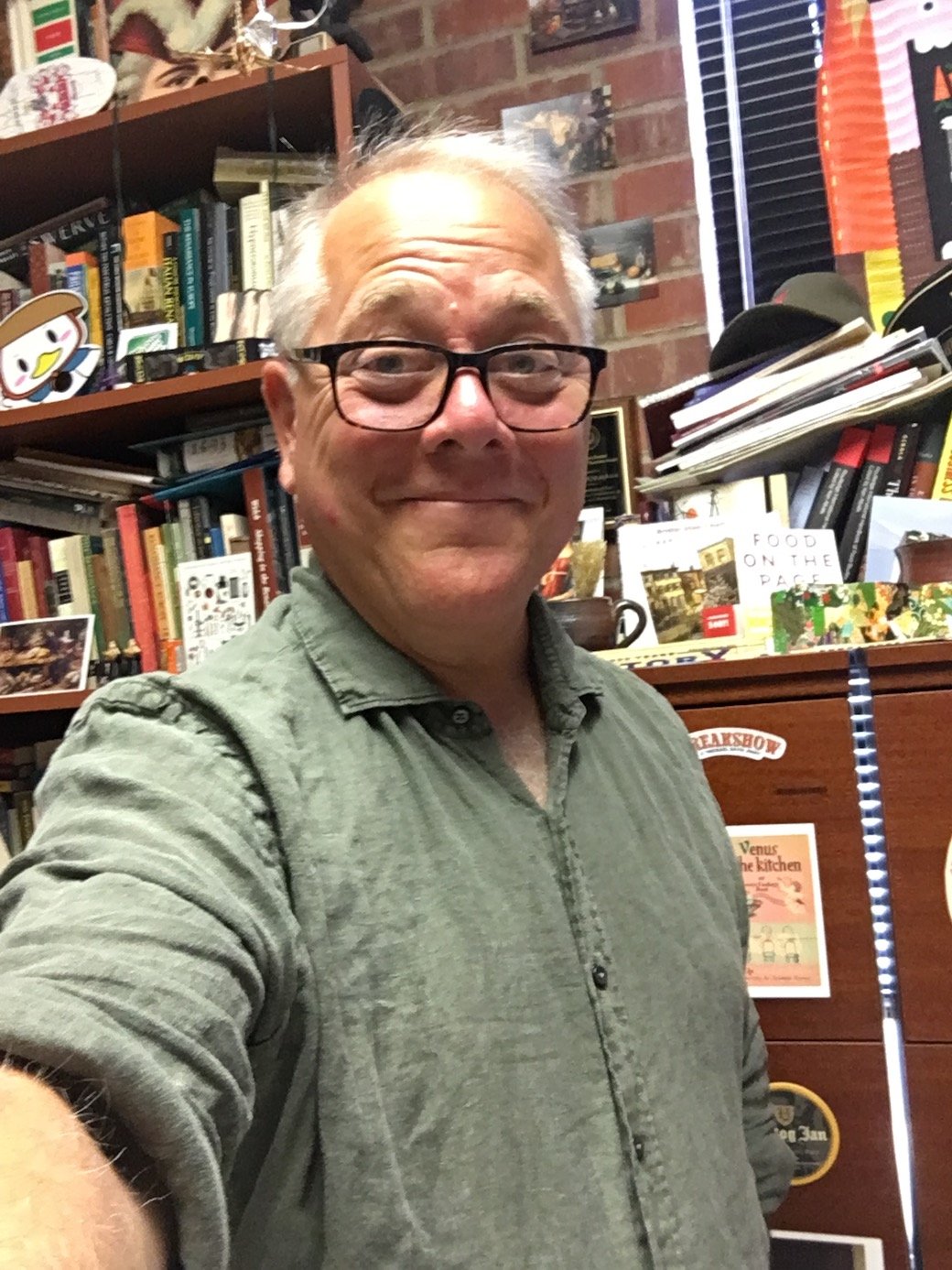

Silvio Lettrari has several billion pets. Pets he cannot see.

That’s because they’re bacteria — and they have a crucial job to do in the baker and pasta-maker’s sourdough pasta factory.

“It’s kind of like a relationship with a dog or something,” he said. “I’ve always treated them with respect because they’re alive — even if you can’t see the little buggers.”

Sourdough is a potion mixed from natural yeasts and bacteria that’s used to leaven bread. It’s also essential to many artisanal and European breads. That’s how Lettrari — who came to Kaslo, B.C., from Bavaria in the 1970s — started on the path to pasta: he wanted to eat better bread, and making it himself was the only way to get it.

He wasn’t alone. People in the mountain hamlet loved his sourdough bread. For many, it was the only bread they wanted to eat.

“Within a short time, people came to me and said: first, the flavour (is better) — and I can digest it better,” he said.

Vancouver-based dietitian Cristina Sutter said that makes sense.

Sourdough bread is easier to digest for people with irritable bowel syndrome, a digestive sensitivity to certain food high in sugar — including most wheat products — that causes stomach pain and bloating.

About 12 per cent of Canadians suffer from the condition, and those numbers are increasing, she wrote in an email.

For Lettrari, it was an incentive to start experimenting.

“Pasta is the only other product that is heavy in wheat,” he said, echoing clients who were telling him they’d stopped eating pasta because of digestive troubles.

“Sourdough, if you could incorporate it somehow (into pasta) would definitely help. That’s what sparked the thought.”

It’s a decision that kicked off almost a decade of culinary trial and error. Sourdough cultures are fickle, responding to changes in humidity, temperature, even changes in atmospheric pressure.

So is pasta. Making the dry noodles that line supermarket shelves — such as macaroni, spaghetti or picchiarelli — demands finding a precise balance between durum semolina flour, water and salt, to make sure the dough stays together as it’s shaped and dried.

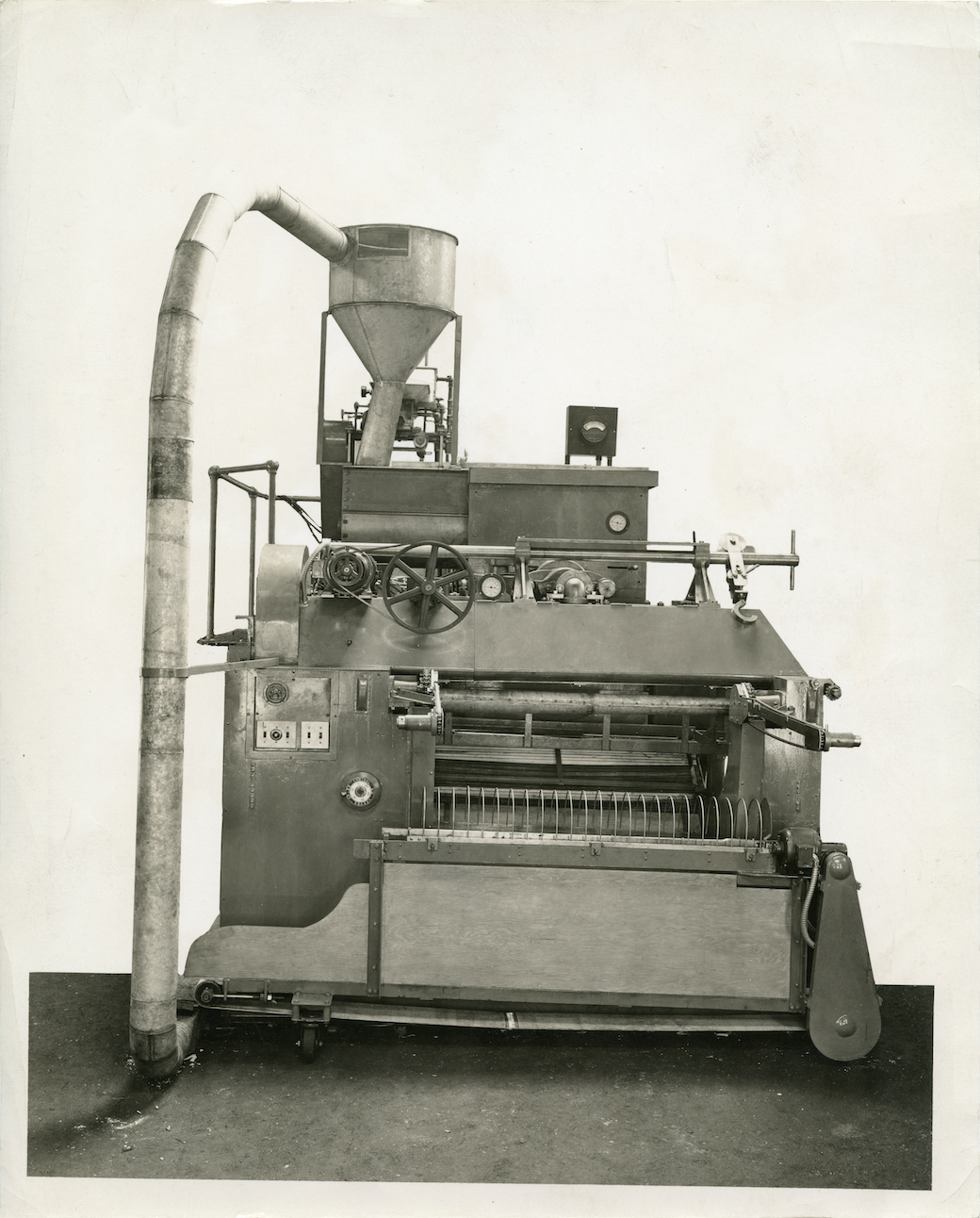

“I invested $30,000 in a very small Italian pasta machine. I wasn’t looking to make a company or produce for sale — I just needed to find out if it could possibly work. And it actually worked!”

That doesn’t surprise Ken Albala, a professor of history and food studies at the University of the Pacific, in San Francisco.

Sourdough pasta was once common in Italy, he explained. However, as the country started to industrialize in the mid-19th century, and pasta became a manufactured product, these recipes fell into obscurity. It’s still possible to find some of these dishes, he said, but they’re extremely regional and mostly unknown.

However, halfway around the globe, fermented pasta feeds millions of people every day. Fermented noodles are common in several Asian countries, he said, forming the basis for common dishes such as pho.

These noodles are produced with slightly different techniques than those used by Italian pasta makers and Lettrari — many are made with rice flour instead of wheat, and shaped using different techniques — but they are undoubtedly fermented, sourdough-like pastas Albala said.

Albala could have guessed that Lettrari is selling his sourdough pasta as a novel product. In fact, he expects most Italian pasta experts would be horrified at the idea — and Lettrari concurred.

“I tiptoed my way with the Italians, with the company I bought the machine from,” he said.

“I knew right away that if I started saying sourdough, or fermented, they’d say: ‘You’re crazy, forget it. We’re not going to sell you anything,’”

Only after several years of producing sourdough pasta successfully did Lettrari mention his success to Italian pasta makers.

They were intrigued, especially when, a few years ago, he announced he wanted to make spaghetti — the crown jewel of pasta — and started looking into an industrial-sized machine that can produce up to 400 kilograms of pasta an hour.

“Spaghetti is different, it's much more delicate and there are a lot more parameters you have to watch. Otherwise, you're not going to be successful. And here I come along and I want to make sourdough spaghetti.”

Last year, he made another investment in his journey with sourdough pasta, investing $600,000 in developing fermented spaghetti with help from a $46,625 grant from the provincial and federal governments. Part of this investment is a new pasta-making machine that should arrive in the next few months, pending shipping delays caused by the pandemic, and that will be accompanied by an Italian pasta-making expert.

Even Barilla, the U.S.’s top-selling pasta brand, has shown interest in his sourdough pasta, ordering eight cases to their Florida headquarters, Lettrari said.

For Albala, that kind of corporate interest reflects long-standing stories about sourdough bread that have cycled through the food industry over the past century.

In the early 1900s, concerns over additives such as chalk in industrially produced bread led to a health food movement that encouraged home baking. That focus on home-baked bread — particularly sourdough — being healthier re-emerged in California in the 1960s and 1970s where hippies painted it as more natural and virtuous than bread made in factories.

“These health food movements distrust the (commercial bread) industry. And then suddenly they think 'Oh, we want it the way it’s always been made’ — which means what they imagine bread to have been like.”

It’s a line that’s come back with a vengeance in the past two decades, as consumers have become more aware of how food shapes the digestive bacteria in their gut, and an increasing number of people have started experiencing gluten intolerances.

Sourdough, and other fermented foods, became a way to manage these ailments, and large companies such as Barilla have tried to expand their product lines to meet this demand.

“I think the next decade will probably bring new kinds of bread (or pasta) we haven’t eaten before, without gluten or whatever it may be, despite this (pandemic-related) flurry of interest in sourdough,” Albala said.

Still, Lettrari is unconcerned. His sourdough is unique, its bacteria shaped by the mountains and rivers surrounding his rural pasta factory — and most importantly, the pasta they produce tastes good.

“It’s not a heavy-duty flavour. It’s very light. It’s one of those fleeting moments. Just try it and see.”

Marc Fawcett-Atkinson/Local Journalism Initiative/Canada’s National Observer

Comments

Good information here thanks .

This is brilliant. Had sourdough noodles many many moon ago, and have missed them. I shall be searching for these.

I will pass this to Silvio thou. I hope your methods and recipes have a patent, and also filed with US patent office. Why else would a US pasta maker order 8 cases, but to try and reverse engineer the process then call it their own.