Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Quadra Island, B.C., resident Mike Windrim has logged a lot of miles and doled out a lot of money over the years to get the medical care he needs.

The 66-year-old was diagnosed 14 years ago with a bone marrow disease that affects the normal functioning of his internal organs.

So, like many other residents of rural and remote communities in B.C., he has to travel off island, and long distances for specialized care in urban centres.

In doing so, he figures he’s spent well upwards of $10,000 on gas alone, not including food and hotels he had to cover for regular visits to Victoria or Vancouver.

“Just a trip to the hospital down there in Victoria where you have to stay in hotel can cost you one thousand bucks easily,” Windrim said.

“It’s a lot of money, especially for someone on a lower income,” said Windrim, who is on a federal disability pension.

He said he was lucky because his community has stepped up with various supports and assistance for him and his family.

“I would have been unable to afford a significant amount of the medical care I have received over the years,” he said.

“Without that care, my outcome would certainly have been different.”

Small population densities across large geographies create many challenges for health planners, but also for patients that have to access medical services, according to Jude Kornelsen, co-director of the Centre for Rural Health Research (CRHR) at the University of British Columbia.

But out-of-pocket expenses tied to travelling long distances for health care is a hot button issue for rural or remote communities, Kornelsen said.

“BC Emergency Health Services, which get really sick people where they need to go when they need to be there, is fantastic,” Kornelsen said.

“But the out-of-pocket spending was something that came up really clearly when we surveyed rural communities about their challenges.”

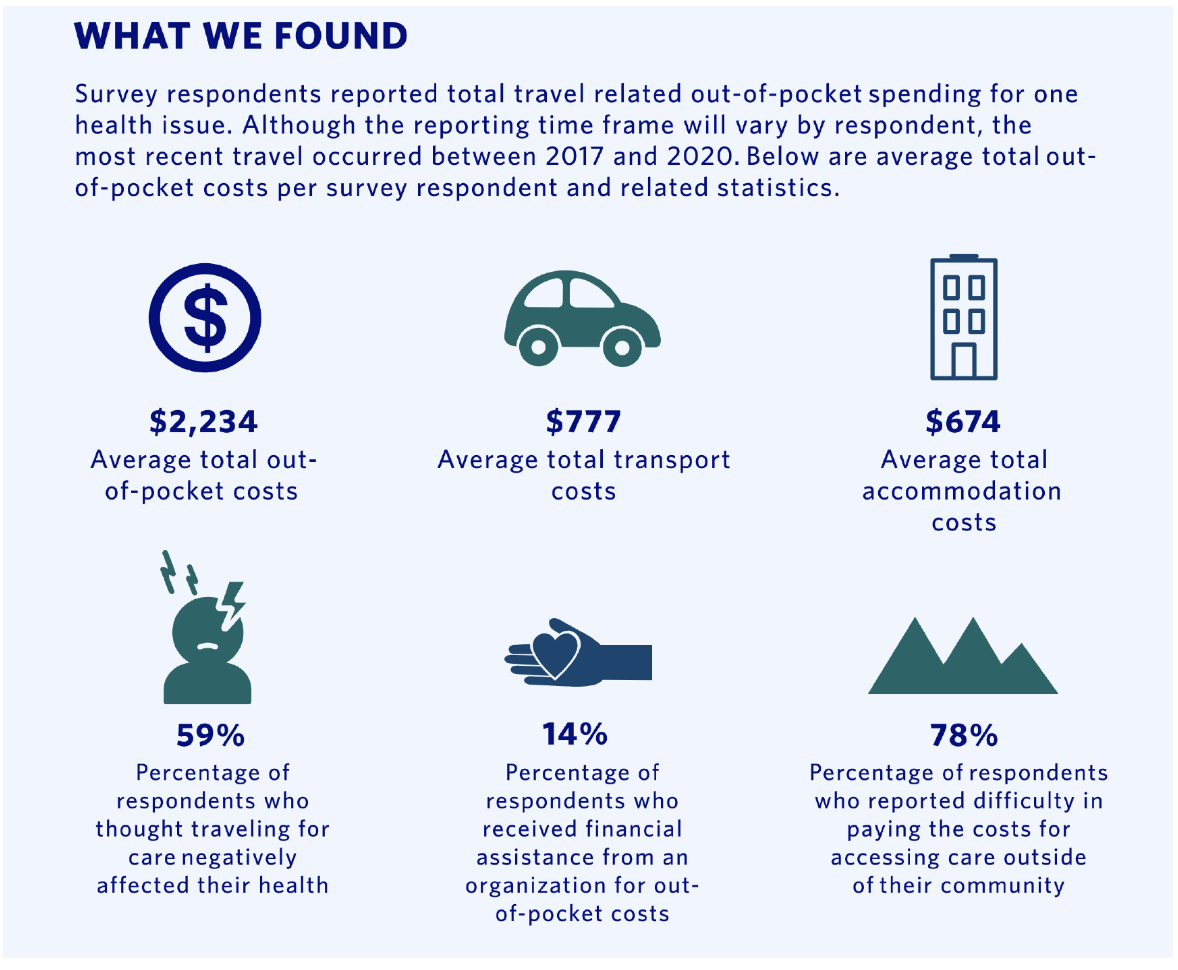

Rural B.C. residents asked about the issue said they paid an average of $2,200 in out-of-pocket expenses for visits related to a single health condition, according to recent CRHR survey.

Seventy-eight per cent of rural residents surveyed reported difficulty in paying the costs associated with seeking medical care outside their community.

“I’d heard the stories, but to see the numbers on paper when people took account of their expenditures, it was eye-opening,” Kornelsen said.

“Every person in a rural community will have a lot to say about out-of pocket costs and transportation because it affects, if not someone individually, then it will affect family members or neighbours who need care.”

The next steps are to discuss the survey findings with rural stakeholders and patients and link them to the province to devise public support to access health care, she said.

Residents on neighbouring Cortes Island also face a two- or three-ferry journey and long drives for care, said Cortes regional director Noba Anderson.

Residents in rural areas certainly recognize they have to travel for care, but they have to face a trifecta of out-of-pocket expenses, lack of public transport and the stress of travelling long distances while unwell, Anderson said.

Those that don’t have vehicles often rely on friends or family to get off island, but with the pandemic that has gotten more difficult, she said.

“I think the barriers to accessing health care (for rural residents) are much more complex than just money,” Anderson said.

“People who struggle with physical, financial or mental health disabilities, or lack transportation, that can make accessing care and services prohibitive, so people can suffer for a long time.”

Ed Staples, president of the B.C. Rural Health Network, said the survey around out-of-pocket expenses makes it clear rural residents are facing obstacles getting the medical care they need.

“It's more than just a problem,” he said. “It's a situation where people just can't get the care because they can't afford to pay for the travel costs, or the accommodation, or meals or whatever.”

He and his wife, both in their 70s, are in a lucky position to be able to absorb the extra costs of travelling for health care, Staples said.

But many other household budgets cannot withstand unexpected expenses in the thousands of dollars, especially when someone is ill, he said.

And though the high costs associated with travelling for health care are provincewide, the remedies are inconsistent and vary community by community, Staples said.

Some small communities have volunteer transportation programs, or there are charitable residences in some cities to house rural residents, he said.

There are also federal tax credits, and some travel subsidies provided by the provincial government, he added.

“There are lots of piecemeal approaches to this problem, but what’s available depends where you live,” Staples said. “And not everybody knows what’s available and that’s a big part of it.”

Windrim wholeheartedly agrees. He’d known about and uses the B.C. Travel Assistance Program (TAP) which helps cover some costs of private transportation carriers such as bus companies and BC Ferries.

But it wasn’t until this year, when he started dialysis for kidney failure, that a social worker at the medical centre determined his income level made him eligible for financial support for his travel costs from the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction.

“I wasn’t aware of it,” Windrim said.

“Not until the (staff) asked me the right questions and did the legwork to get me hooked up to have my expenses paid.”

Windrim stressed that every person travelling from a rural community for medical care should ask what supports are available and talk to social workers at the medical health facilities they are attending.

“Because unless you have people like that going to bat for you, you're going to pay for it yourself and not know,” said Windrim, adding he didn’t know where to look for that information himself and it wasn't readily available.

“The government doesn't advertise it. It’s a real problem. I went many years paying for it all myself,” he said. “For many years, and that’s money I can’t get back.”

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada's National Observer

Comments

Its the same in Nova Scotia, where hospital care is centralized in Halifax. For cancer or any specialized treatment you often have to travel to a regional center such as Yarmouth, Kentville or Truro. Local community Healthcare facilities are understaffed, frequently closed, and an ambulance may take up to an hour to reach you if you have an heart attack or accident. What is needed is a standard of care for Rural Healthcare. Then we would better able to allocate our Healthcare resources on a realistic basis.

Check out Renfrew and Renfrew County Ontario which uses paramedics . Very successful. 2.5 hours North of Kingston ON. On CBC Radio one White Coat Black Art with Doctor Goldman.

https://www.cbc.ca/radio/whitecoat

How the pandemic sparked a new program that connects rural Ontarians to rapid-response health care.

Living in Cold Lake AB we are 3 hours from major centre of Edmonton and there is continuous trips to the big city for appointments. Time to use technology

This is just another reason BC (and all of Canada) needs a publicly owned and operated highway bus network. See this new campaign for BC wide highway bus service https://bcwidebus.wordpress.com/