Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

City council meetings in London, Ont., look a little bit different these days.

Of course, they are largely conducted via video-conference, this being the COVID-19 era, but its participants are also more diverse.

The slate of councillors elected in the province’s first ranked ballot experiment include newcomers who are young, gay, Black and Indigenous, boosting the claims of the preferential voting system’s advocates that it creates a more democratic, more equitable, and more inclusive political system.

It's also a reform that Toronto is looking to use in its 2022 municipal elections.

“I chose to run because the ranked ballot seemed much more approachable as a young woman and as a Black woman,” said Arielle Kayabaga, who won a close race for a vacant seat in London's Ward 13 on the eighth round of counting back in 2018. “I felt that I could bring something to the table and focus on that instead of focusing on who has more money and who could slander the other better.”

Less wedges, more connection

In ranked ballots, candidates seek to win the second- and third-choice votes of their competitor’s supporters, which advocates in general — and some participants in London’s 2018 election in particular — say encourages candidates to appeal to a broader set of constituents.

Shawn Lewis, London’s first openly gay city councillor, said ranked ballots “created an interesting dynamic where I feel like candidates across the city were actually talking to each other more about city-wide issues rather than just being bubbled in wards and focused on getting to that 33 per cent of the vote to win the race.

“It took away people's ability, I feel, to be one-issue candidates, and if they were one issue, they very quickly fell to the bottom of people's rankings,” he said.

Kayabaga said she still knocked on the doors of houses with lawn signs endorsing other candidates trying to convince them to put her down as an alternate choice.

“It was really good for us to connect with everybody in the ward, not just the people who didn't have signs” supporting other candidates, she said.

It may have paid off for Kayabaga, who ended up with 139 more votes than her nearest rival, John Fyfe-Millar, after six other candidates were eliminated. (She started with 107 more than him in the first round.)

“It took quite a bit of votes before we got there,” she said, but that meant “some people who didn't make me their first choice still feel like they participated in electing their city councillor.”

Coming to Toronto?

The benefits and drawbacks of ranked ballots will be on the minds of Toronto's 26 elected representatives this month as they consider their city clerk’s recommendation that council drop plans to introduce it for the 2022 election.

Jesse Barke, one of the younger members of the Ranked Ballot Initiative of Toronto, says he is hopeful they get it done.

“As the world and our cities become more polarized, we need a lot less negativity and ways to get together in ways that are constructive,” he said.

Barke said that Toronto, which boasts of being the most diverse city in the world, can’t ignore that London's experience showed ranked ballots help boost historically underrepresented candidates.

More than half of the people living in Toronto in 2016 identified themselves as members of a visible minority, the technical term for non-white, compared to not even one-sixth of council. (One in six is also roughly the portion of non-white people in London, which is one-tenth the size of Toronto.)

“City council should in some way reflect the diversity of the population,” Barke said. “All the citizens of the city need to receive the attention they deserve.”

Still room for dirty tricks, for now

But this new way Ontario municipalities can (since 2016) collect and tabulate their local election results did not entirely remove the motivation or the space for dirty tricks in London.

A police investigation is ongoing after a political consultancy affiliated with two male candidates, Blackridge Strategy, launched anonymous personal attack websites that targeted two incumbent female councillors.

One of them was former councillor Virginia Ridley, who Kayabaga describes as “my mentor at the time.”

She said the attacks seek to remove women “from public spaces and leadership roles by fear-mongering and fear tactics and slander and all the things they did do and will continue to do if they are not stopped.”

Two Londoners are facing charges in the affair, including candidate Randy Warden for failing to identify himself on election campaign advertising. None of the allegations have been proven in court. Blackridge has defended the content of the websites as accurate.

Dozens of issues, no vote-splitting

The divisive issue in London in 2018 was about whether to build a bus rapid transit system, Lewis said, but on the doorstep, a dozen other issues would also be on voters’ minds.

“Green bins was another popular one. We don't have green bins yet, and there is a lot of interest from the public on when we are going to get those,” said Lewis, who defeated the city’s longest-standing incumbent councillor, Bill Armstrong, in London’s Ward 2.

The former staffer for federal NDP MP Irene Mathyssen said he would have dropped out under the previous system, which often featured three or four candidates splitting the vote against Armstrong, if he thought another candidate had a better chance of beating him.

This time around, the only other contender entered the contest late and ended up knocking on doors with Lewis, who won in the first round with 3,483 votes to Armstrong’s 1,799. Most of the 173 first-choice votes for the other candidate, Alan Jackson, would have gone to Lewis in any run-off count.

Lewis said London could improve its process the next time around by separating the council election from the school board election, which did stick with a first-post-the-post count.

The initial staff report (PDF) following the election by London city clerk Cathy Saunders noted ranked ballot results could not trickle in polling place by polling place since the 50 per cent plus one vote threshold meant every vote had to be counted.

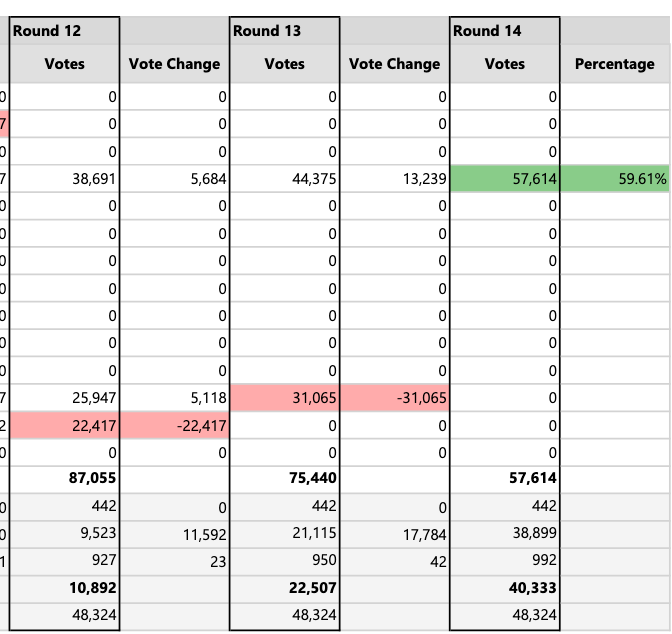

Saunders said only one candidate was eliminated each round for the sake of transparency. In the case of the hotly-contested mayoral race, this meant 14 rounds of counting to eliminate all 13 other contenders before Ed Holder could be declared victorious.

The staff report said 31 per cent of voters only selected one candidate in the mayoral race, while 47 per cent ranked three candidates and 22 per cent ranked two.

The outreach to explain the new process meant staff worked evenings and weekends from March until mid-October, Saunders said.

The report said the city paid more than $470,000 plus tax to Dominion Voting Systems for a “turnkey election management solution” and that total costs for the 2018 election came to just under $1.8 million.

The report estimated that $515,446 of that could be directly attributable to changes needed to use ranked choice voting.

Toronto, which needs to replace its own vote-counting equipment, should note that London’s requests for the province to certify the equipment being used or fund an auditor to monitor the process were declined or ignored.

On election night, only eight winners were announced, with counting resuming the next day at 10 a.m., and all unofficial results published by around 3 p.m. In the end, six newcomers joined eight incumbent council members following the historic vote.

Morgan Sharp / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments

Good to know that the ranked ballot in London is electing more diverse candidates. I hope their next move in improving their democracy will be to redraw the boundaries and have multi-member wards. Then their system will be proportional.

Alistair Sharp mentions two possible favourable results of ranked ballots in municipal elections: more diverse candidates being able to run with no fear of splitting the vote; and less emphasis on wedge issues. It's also possible that a candidate who might have won with a small share of the vote in the first round might be defeated in subsequent rounds. However, it's interesting to note that in this particular election, all of the candidates who won would also have won under first-past-the-post (details in Wikipedia). That's OK. The arguments posited by Alistair Sharp make sense and ranked ballots provide some protection against the election of a candidate supported by a minority of voters. This is one step on the way to a superior way of electing our representatives. Hopefully London will continue on to the next step: the use of multiple-member wards, ensuring that a diversity of views are represented as a matter of course in proportion to how people voted.