Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This article was originally published by The Guardian and appears here as part of Canada's National Observer's collaboration with Climate Desk.

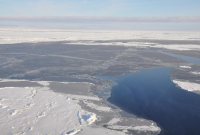

For the first time since records began, the main nursery of Arctic sea ice in Siberia has yet to start freezing in late October.

The delayed annual freeze in the Laptev Sea has been caused by freakishly protracted warmth in northern Russia and the intrusion of Atlantic waters, say climate scientists who warn of possible knock-on effects across the polar region.

Ocean temperatures in the area recently climbed to more than 5 C above average, following a record breaking heat wave and the unusually early decline of last winter’s sea ice.

The trapped heat takes a long time to dissipate into the atmosphere, even at this time of the year when the sun creeps above the horizon for little more than an hour or two each day.

Graphs of sea-ice extent in the Laptev Sea, which usually show a healthy seasonal pulse, appear to have flat-lined. As a result, there is a record amount of open sea in the Arctic.

“The lack of freeze-up so far this fall is unprecedented in the Siberian Arctic region,” said Zachary Labe, a postdoctoral researcher at Colorado State University. He says this is in line with the expected impact of human-driven climate change.

“2020 is another year that is consistent with a rapidly changing Arctic. Without a systematic reduction in greenhouse gases, the likelihood of our first ‘ice-free’ summer will continue to increase by the mid-21st century,’ he wrote in an email to the Guardian.

This year’s Siberian heat wave was made at least 600 times more likely by industrial and agricultural emissions, according to an earlier study.

The warmer air temperature is not the only factor slowing the formation of ice. Climate change is also pushing more balmy Atlantic currents into the Arctic and breaking up the usual stratification between warm deep waters and the cool surface. This also makes it difficult for ice to form.

“This continues a streak of very low extents. The last 14 years, 2007 to 2020, are the lowest 14 years in the satellite record starting in 1979,” said Walt Meier, senior research scientist at the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center. He said much of the old ice in the Arctic is now disappearing, leaving thinner seasonal ice. Overall the average thickness is half what it was in the 1980s.

The downward trend is likely to continue until the Arctic has its first ice-free summer, said Meier. The data and models suggest this will occur between 2030 and 2050. “It’s a matter of when, not if,” he added.

Scientists are concerned the delayed freeze could amplify feedbacks that accelerate the decline of the ice cap. It is already well known that a smaller ice sheet means less of a white area to reflect the sun’s heat back into space. But this is not the only reason the Arctic is warming more than twice as fast as the global average.

The Laptev Sea is known as the birthplace of ice, which forms along the coast there in early winter, then drifts westward carrying nutrients across the Arctic, before breaking up in the spring in the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard.

If ice forms late in the Laptev, it will be thinner and thus more likely to melt before it reaches the Fram Strait. This could mean fewer nutrients for Arctic plankton, which will then have a reduced capacity to draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

More open sea also means more turbulence in the upper layer of the Arctic ocean, which draws up more warm water from the depths.

Dr Stefan Hendricks, a sea ice physics specialist at the Alfred Wegener Institute, said the sea ice trends are grim but not surprising. “It is more frustrating than shocking. This has been forecast for a long time, but there has been little substantial response by decision-makers.”

Comments