Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

More than 10,000 Canadians have died due to COVID-19, a grim milestone reached by a pandemic that is far from over.

Twenty-eight new deaths reported in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta pushed the death toll to 1,001 on Tuesday.

Canada crossed the threshold of 5,000 deaths on May 12, a little over two months after the first death was reported.

COVID-19 case counts slowed across the country through the summer, but have taken a big jump in many areas this fall, with new daily highs reached regularly in Central and Western Canada.

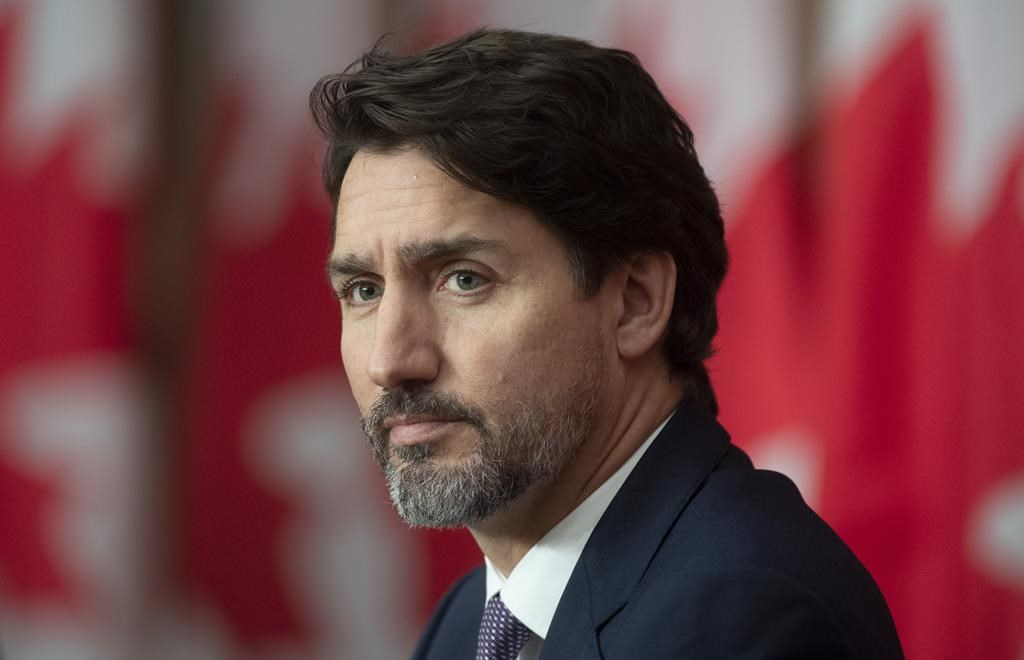

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called the pandemic a "horrific national tragedy," and warned that Canadians should brace for more.

"Families have lost loved ones, been devastated by these tragedies, and we need to know that there are more tragedies to come," he told a briefing in Ottawa.

The death toll has climbed much more slowly since April and May, when outbreaks in long-term care homes and a lack of medical knowledge about the novel coronavirus resulted in a higher proportion of fatal infections.

However, the pandemic has grown deadlier over the past month. More than 600 COVID-19-related fatalities have been reported in October so far compared with 165 COVID-19 in September, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Ontario reported 827 new cases of COVID-19 on Tuesday, and four new deaths due to the virus.

Quebec, where residents in its biggest cities will have to live with partial lockdowns for at least another four weeks, reported 963 new cases of COVID-19 and 19 more deaths.

Manitoba tallied its highest daily number of COVID-19 cases since the pandemic began, with health officials reporting 184 new infections on Tuesday and three more deaths.

Alberta reported another two deaths from COVID-19.

The pandemic's second wave could jeopardize large gatherings with friends and family over Christmas after a reined-in Thanksgiving.

"It’s frustrating knowing that unless we’re really, really careful, there may not be the kinds of family gatherings we want to have at Christmas," Trudeau said.

He sought to spur hope ahead of a "tough winter."

"We will get through this. Vaccines are on the horizon. Spring and summer will come and they will be better than this winter," he said.

But the current situation he summed up with a single verb.

"This sucks. It really, really does."

The prime minister encouraged residents to continue to follow the advice of local health authorities, despite frustrations over conflicting information on Halloween as well as varying COVID-19 testing requirements for students.

Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada's chief public health officer, has suggested hockey sticks as a tool to hand out Halloween treats, while others are resorting to candy chutes or self-serve stations. But the Ontario government has recommended against trick-or-treating in parts of the province that have been hardest hit by the resurgence of the novel coronavirus.

Meanwhile, school reopening plans sowed confusion about what symptoms in students demanded COVID-19 tests, triggering massive lineups at assessment centres and overwhelming laboratories where the tests are processed.

And Quebec Premier François Legault had his own ideas Tuesday about the prospects for a festive holiday in December.

"I really hope and I'm confident that in 28 days we'll be able to maybe not have big parties, for Christmas, but to be able to see our families," he said in his own briefing.

In Prince Edward Island, chief public health officer Dr. Heather Morrison had unwelcome news for residents hoping to reunite with family from outside the Atlantic bubble over the December holidays.

"While we are always evaluating our decisions and guidance using the best available evidence, I do not expect right now that we will be reducing the 14-day self-isolation requirement prior to the Christmas holiday season," she told a briefing in Charlottetown.

Under their bubble arrangement, the Atlantic provinces limit who can enter and require people who do come in from outside the region to quarantine for two weeks.

Mixed messaging threatens to chip away at trust in public health advice, said Tim Sly, an epidemiologist and professor emeritus at Ryerson University's School of Public Health.

Dance studios in Ontario's "hot zones" have been allowed to stay open, while gyms have been forced to shutter along with cinemas, casinos and performing arts venues, he noted.

"Quite honestly I don’t know why a distinction is made between those two," Sly said.

Trudeau said circumstances have changed since the spring, when little was known about the novel coronavirus and there was one main message: "Everyone stay home."

"We can be a little more targeted (now). But yeah, that means a little more complicated in our messages," he said Tuesday.

Epidemiologists across the country have stressed the need for massive testing in order to stop the spread of the virus.

Sly pointed to Germany as a model, despite a recent spike in case numbers. Authorities there have made both rapid testing and "open public testing," which lets asymptomatic people access tests, crucial weapons in the war against viral resurgence.

"Testing is absolutely key and, at the other end after the fact, contact tracing. And we’ve been not prepared for these things — behind the 8-ball," Sly said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 27, 2020.

Comments