Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

I trudged down the brightly lit hallway, slightly out of breath as I searched for the room I’d remain inside for the next 10 days.

It looked just like your average hotel — somewhere you’d stay for a conference or a work trip, back in the days when we had those. Except it was eerily silent, I’d been escorted to the elevator by a masked security guard and I was there because I had COVID-19.

As I reached the end of the corridor, I spotted an open door on my right and hustled inside, shutting it behind me as quickly I could. It had been two days since I developed a strange cough, seven hours since I found out I had the novel coronavirus.

I set down my bags shakily and sunk onto the bed, trying to make sense of the absurd situation.

The cough started Sunday while I walked home from buying a coffee in Kensington Market. It was small — maybe one every half-hour. But it also felt different than any cough I’d ever had, rattling deep in my lungs in a way that felt unsatisfying and unfamiliar.

I had planned to buy groceries on the way, but instead I went straight home, a pit in my stomach. I let my roommates know, my boyfriend and I booked COVID-19 tests and I wore a mask inside my house, but I didn’t really think I could possibly have the virus. We’d been so careful, wearing masks, practising social distancing and washing our hands often.

“It could be anything,” he told me.

But by Monday night I was shivering feverishly under a pile of blankets, muscles aching and chest congested, while my partner had lost his ability to smell. His test came back positive that evening, then mine followed the next morning. My roommates and I had talked before about what we’d do in this situation — isolate in our rooms, wear masks, sanitize thoroughly — but in the moment it felt surreal.

“You literally have COVID,” my roommate texted me from the other room as we tried to sort out next steps. “It’s kind of the worst-case scenario.”

I live in a small Toronto house with three other people, and I share a bathroom with the roommate I was texting, a friend so close he’s practically family.

His room is separated from the bathroom by a glass door and a curtain, the bed a metre from the entryway. Every time I went to the washroom, I felt like each of my breaths was poison, seeping through the cracks in the door and into the room where he slept. It seemed like only a matter of time before I would infect him.

I remembered seeing a press release about a City of Toronto COVID-19 isolation hotel, and that seemed like my best shot to keep my roommate safe. So when the city’s COVID-19 hotline opened Tuesday morning, I called, desperately hoping to secure a spot.

This phone call was crucial: Somewhere along the way, someone had input my cell number wrong, a vital error that I was able to correct early. And I was able to ask Toronto Public Health to flag my file as urgent, something that allowed me to get a call back two days before my boyfriend, even though he got his results back 12 hours before I did.

By 11:30 a.m., I was on the phone with a kind but efficient contact tracer. As I explained the layout of the house, I heard her fingers flying across her keyboard.

“I’m filling out your application right now,” she said.

At 1:30 p.m., she called to confirm I had a room — at an unoccupied hotel that had been converted into the Toronto Voluntary Isolation Centre — and that a taxi would come to pick me up.

“Can you be ready in 90 minutes?” she asked.

Those minutes were a blur, a flurry of phone calls and frenzied packing. The contact tracer ran me through the details: I would spend 10 days in the hotel, and meals would be delivered three times a day, except for my first 24 hours, in which I should be prepared to feed myself just in case the caterers couldn’t make an extra meal on short notice. There would be coffee and tea and disposable cups. I should bring everything I'd need to manage my COVID-19 symptoms, and since no one would enter my room except me, I might want to bring a few spare dishes and some cleaning supplies.

If I needed anything else, friends and family could drop it off. I would be allowed to leave if I wanted to, but otherwise, I would stay inside my room. Most importantly, I would not need to pay a cent.

“Try to treat it like a spa weekend,” the contact tracer told me. "Relax."

When I arrived, I found a letter on the counter from Toronto’s medical officer of health, Dr. Eileen de Villa — one given to every resident of the Voluntary Isolation Centre.

“Thank you for agreeing to stay at the centre,” it said. “You are protecting others from getting infected, especially your family or anyone else you live with. You should be proud of your choice. Toronto is grateful for it.”

With the door shut behind me, I felt relieved. Like I was no longer a risk to anyone I love.

The room itself was calm and comfortable, awash in soothing greys, soft lighting and warm-toned wood. The window faced an enormous empty parking lot, suburbia sprawling out in the distance. I had the essentials: a tea kettle, a mini-fridge, a sparkling clean bathroom, a desk and a reading chair.

The more I looked, the more I noticed little, typical hotel things were missing: the closet lacked coat hangers, only one of the beds had sheets, there was no Bible in the drawers and a shelf that was clearly meant to hold an iron was empty.

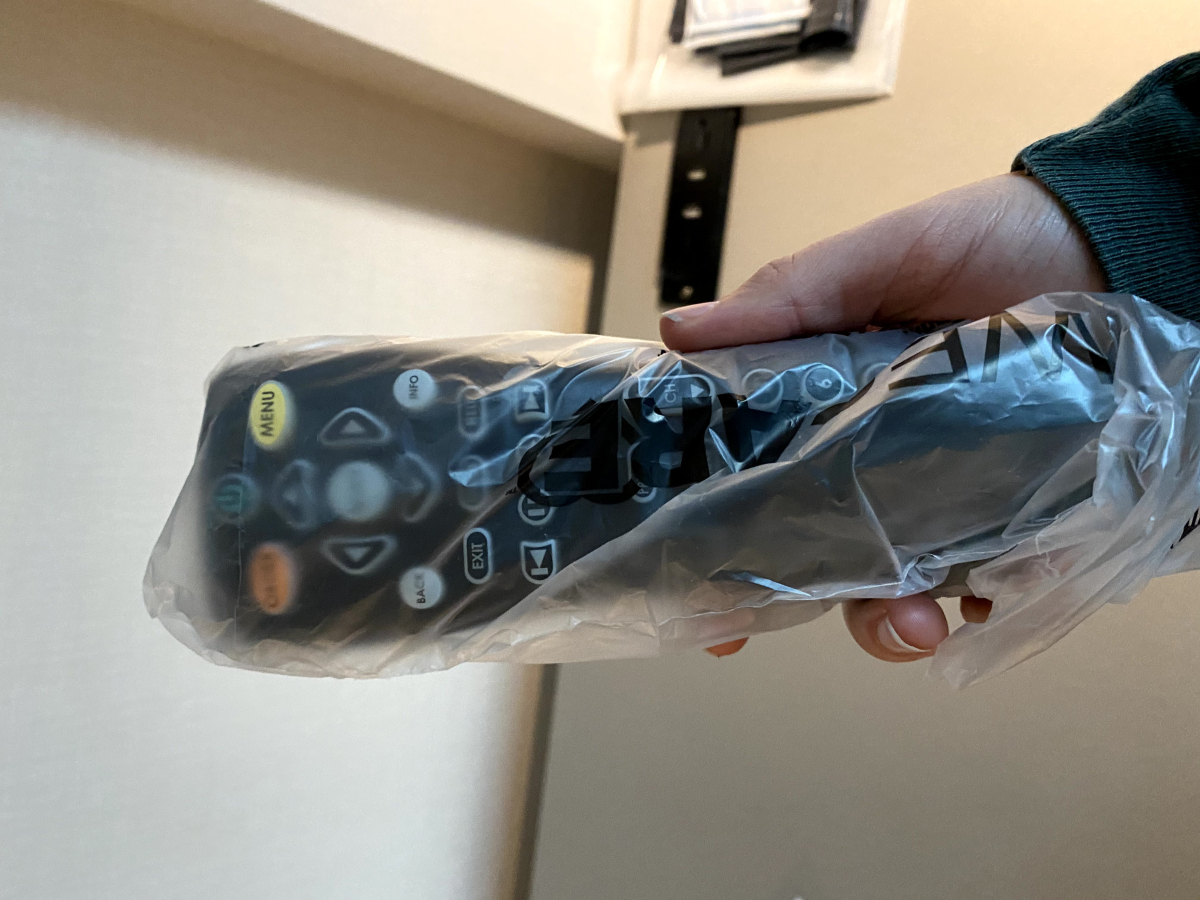

It seemed like the space had been designed so that as few items as possible would need to be disinfected later. Even the TV remote was wrapped in a layer of plastic that I was instructed not to remove.

Most of all, the room was quiet. Aside from the crinkling of a paper bag that signalled the arrival of a meal, I can count on one hand the number of sounds I heard during my stay: twice, hotel staff had to shout at another guest, ordering them to stay inside their room and close their door. Once, I heard a faint laugh through the wall. I started keeping the TV on to fill the silence.

Much to my delight, I received my first meal that night, a wholesome chicken dish. I started tweeting out photos of the room and the food, mostly to keep myself entertained.

I cracked jokes about the whole saga and my own declining sense of smell and taste — yet another COVID-19 symptom — but privately, there were scary moments.

Though my fever and muscle aches were gone before I’d arrived at the hotel, I was so exhausted that I’d have to lie down after washing two dishes. At first, even sitting up for a couple of hours was too much. My nostrils burned every time I took a deep breath.

My ability to smell was completely gone by my third day in the hotel, and I could only taste whether something was sweet, salty, bitter or sour. I was terrified that those senses might never come back. I tried sniffing a bottle of peppermint essential oil, something that would normally be overwhelming, and started to cry when my nose picked up absolutely nothing.

Normally, I have a robust appetite. That vanished. Kind, encouraging Toronto Public Health case managers who called me daily to check in encouraged me to keep eating anyway, so I spent entire days forcing myself to finish every single bite of my meals, even if it took hours. Even if dinner arrived before I’d finished lunch.

I have to give kudos to the chef behind these meals, who put together a menu that happened to include all my favourite comfort foods: tomato soup, orzo, macaroni and cheese. All things that have a lovely texture, even if you can’t taste them.

The chef was also a good sport about my tweets, sending me a kind note and an extra portion of incredible carrot cake on one of my final days at the hotel. That was a real bright spot.

Another upside: the love and support I received from my friends and family. They conspired to send me care packages of tea and snacks, and kept me busy with phone calls and virtual game nights.

The case managers said I might have to stay longer if my symptoms weren’t getting better by the time the 10 days were up. So I rested aggressively, spending as much time lying down as possible.

Bit by bit, I started to feel better. One morning I could smell the peppermint oil again, faintly. The breakthrough food was a waffle with home fries, doused in syrup.

I felt hungry again, then less tired. Days flew by as I watched snow fall, then melt outside my window. And on a Thursday, more than a week after I arrived, I got the all-clear to go home. A paramedic — there’s always one on-site at the hotel, just in case — helped me carry my bags down to the lobby.

Nothing has ever felt as good as the fresh air when I stepped outside, or the enormous hug I got from my boyfriend after two lovely city employees dropped me off outside my house.

Some mysteries remain: My boyfriend and I still don’t know how we picked up the virus. Our best guess is his work, or perhaps my recent trip to the grocery store — my contract tracer told me that the virus is so rampant in Toronto right now that such stories are common. I got sick the day before the city entered a second lockdown, and as I write this, Toronto has reported 553 new cases in the last day.

All things considered, I was lucky to have a mild case, and that I was able to access a resource like the isolation hotel. In the end, it did what it was supposed to do: None of my roommates got COVID-19, and I had a safe, comfortable place to recover. I’m also grateful that my boyfriend remained mostly asymptomatic.

But I don’t want to downplay my experience with the virus, either.

I’m young and active. I was healthy before this. Hiking, rock climbing and soccer kept me sane through this hellscape of a year, and I can usually bike from one end of the city to the other without breaking much of a sweat.

When I was released from the isolation centre, a walk around the block felt impossible. Stairs still leave me lightheaded. If I overdo it and move too quickly, I feel faint and have no choice but to lie down until it passes. I’ve always had excellent circulation, but now my fingers and toes are perpetually freezing.

My hunger signals have gone haywire. I never feel peckish anymore, but I’m struck at random times with a feeling of deep ravenousness that doesn’t go away. I could have eaten an hour beforehand, but it feels as if my last meal was days ago.

Loud noises send a shockwave through my entire body. Something as small as stubbing my toe jolts me to my core. For lack of a better word, I feel fragile.

I’m also endlessly thirsty, as if my body is trying to flush something out. It’s hard for me to fall asleep, but I feel awful if I get any less than 10 hours.

Some people have used what happened to me to claim that masks and distancing don’t work — if I was so careful, they ask, how did I get sick? I think that’s the wrong way to look at this.

In reality, the fact that I wore a mask at home and stayed in my room as soon as I started feeling sick appears to have made all the difference in keeping my roommates safe. There’s also emerging research that shows masks might lessen the severity of illness for those who do fall ill, although I don’t know for sure what happened in my case.

My symptoms are getting better day by day, but progress is slow. I don’t know when I’ll feel like myself again. Every night, I read first-hand accounts from COVID-19 long-haulers, hoping I won’t be one of them.

But I’m also starting to feel hopeful. Today marked the first time I was able to take a short walk at my normal pace.

I’ll take that as a sign that maybe, by the time it’s safe for me to hug everyone I love, I’ll feel well enough to squeeze them with all my might.

Editor's Note: In a new podcast, the Canada's National Observer team takes you behind the scenes of a news organization in the early days of the pandemic. Listen here.

Comments

Emma

Thank you so much for sharing your experience of your illness with such clear detail. WhiIe the effects of the viral infection vary considerably from person to person, your report has given me some context for assessing my own health and what I might expect in the initial stages, should this happen. I am almost 79 years old and approaching a highest risk level. I have been moved to get tested recently because of some upper respiratory congestion, and the result was, happily, a negative test for the virus. Recognizing that it is quite easy to accidently contract the infection even with distancing and masking and washing, places a level of anxiety about how we spend our days upon us all.

Your sharing has helped very much.

Paul in Ottawa

Thank you so much for reading, Paul! I hope you're able to stay safe out there.

Emma, thanks for this steady eyes-open account of your experience with Covid-19. Your actions and how you felt, and how others treated you, all form one model for us to imagine what it can be like. There'll be many different ways it can be for different people. What you've been through gives us one real life example of what to expect and what to do, from onset through isolation to re-entry. This is good, among so many stories we get that are about individuals' really tough times and grief, or are presentations of compiled statistics.

I'm glad you are back in touch with your people, and that your reporting is carrying on for us. Please take it as easy as you'd advise someone else to do. Best wishes for a full return of vitality.

Tim, in Ottawa

Most interesting account, thanks for making it available. An aspect not mentioned was, I assume, the monitoring of your condition to detect if hospitalization might be necessary if symptoms became more severe. Suggest that subject be added if to be updated at this late date (3.Jan.'21) . Happy year and years ahead.