A decade ago, Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah Harmer and neighbours fought a proposal to dig more aggregate out of the Niagara Escarpment on Mount Nemo near a haven for hikers and rock climbers.

The group argued the escarpment, a UNESCO biosphere reserve, was not a good place for another quarry. That application was denied, but now, the company that mines the rocks and stone to feed the Greater Toronto Area’s insatiable demand for concrete is trying again.

Harmer, a Juno Award-winning musician who grew up in a farmhouse there, says the plateau is worth protecting.

“It is so pristine and incredible … and yet it's so close to millions of people. So it's at an interesting crossroads,” she says.

“This is the last place you want to go in below the water table.”

As the GTA grows, the raw materials for concrete have to come from somewhere. It takes 1,760 truckloads to build one kilometre of a four-lane highway.

But should that aggregate come from Mount Nemo? Project advocates and opponents alike are using environmental arguments to shore up their positions.

Quarry owner Nelson Aggregate says sourcing the product closer to where it will be used will ultimately better the environment by reducing the amount of greenhouse gases needed to transport it. Advocates, meanwhile, argue that given the biological significance of the Mount Nemo plateau, it is not the place for more extraction. They also say they’re worried the expanded quarry could bring more trucks, dust and mining blasts closer to their homes.

Mount Nemo is about an hour’s drive from Toronto, in a rural area of Burlington where residents of the homes dotting acres of farm fields get their water from private wells.

Endangered species like the Jefferson salamander live in patches of forest. Also atop the plateau is the Mount Nemo Conservation Area, a lush hot spot for rock climbers and hikers.

Nelson — jointly owned by concrete supplier LaFarge Canada and Steed and Evans Holdings Inc. — already operates a quarry on Mount Nemo, which has been extracting aggregate for about 100 years. The company applied last spring to expand its operations on land to the west and south of its existing site.

Nelson’s last attempt to enlarge its Burlington site, begun in 2004, proved contentious. It was denied in 2012 after years of hearings.

This time around, the application seems to be no less controversial. In 2019, when Nelson announced its intentions but had not yet filed the paperwork, some residents immediately started organizing against it. “The resistance begins,” read a headline from local news outlet Inside Halton.

The roads around the plateau are lined with red and white signs reading, in all caps, “NO QUARRY.”

Not all residents oppose the quarry expansion. Jim Frizzle says he believes environmental concerns can be resolved and sourcing aggregate elsewhere would be “short-sighted.”

“I get a bit miffed at the people who are so dead set against it,” he said. “If we don't get our gravel from Nelson quarry, we'd have to have it shipped in from somewhere else and the cost would be much greater.”

If aggregate doesn’t come from Mount Nemo, the next nearest source is 20 kilometres away, said Kevin Powers of the public relations firm Campbell Strategies, which represents Nelson Aggregate. Over 30 years, the extra truck traffic would add up to 60 million kilometres — enough to travel to Mars, and add a “big, unnecessary environmental footprint,” he said in an email.

“This aggregate is needed, and is well-placed to help the city’s needs and its environmental commitments,” Powers said.

“Opposition to the expansion is centred within a short distance of the quarry (nearby) neighbours,” he added. “Support is broad across the city and the region.”

Burlington city councillor Rory Nisan, whose ward includes Mount Nemo, acknowledged in a phone interview that the situation is complex. (City officials can’t pass judgment until the planning process is further along.)

“It's a little different than pulling aggregate from other areas. It's a 400-million-year-old UNESCO-recognized biosphere,” Nisan said.

“A mining business is going to seek to do more mining, and they have every right to make an application, that’s for sure. Doesn’t mean we have to support it, though… Time will tell.”

The fountainhead

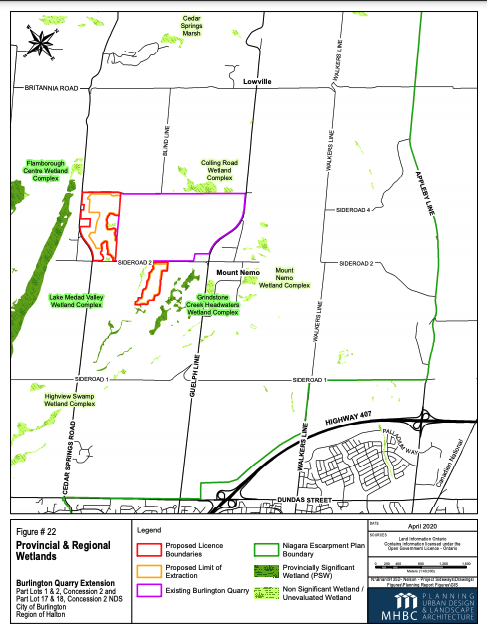

If you look at Mount Nemo on a map, blue lines emanate from the top — tributaries of waterways that flow towards Lake Ontario.

The limestone below the surface there is porous, full of cracks and crevices. In some places, water trickles into sinkholes and dips into underground aquifers, bubbling up unexpectedly in ponds and above-ground creeks.

Harmer, who often visits her parents’ home there, calls it the fountainhead.

“This is the birthplace of all these headwaters,” she said.

The top layer comes from the Amabel Formation, rock formed 400 million years old when the region was a warm, shallow sea. Its past is visible in coral fossils embedded in the stone.

This rock is also excellent quality for mining aggregate, and the history of quarrying on Mount Nemo runs deep. Burlington officials say aggregate has been extracted there for over 100 years, and the existing Nelson quarry has been running since 1953 (the company bought the site in 1983).

The legacy of conservation on Mount Nemo is almost as long.

A few minutes from the Harmer family farm, an abandoned quarry pit scars the escarpment. That site only operated for a few years — a local conservation authority bought up 88 acres of land there in 1959 to stop it from expanding, and the quarry shut down that year.

The change sparked the formation of a committee to protect the escarpment. The result was Canada’s first-ever rule book for large-scale environmental land use, the Niagara Escarpment Plan.

The former quarry land, meanwhile, became the Mount Nemo Conservation Area. On a sunny spring day, turkey vultures float by the cliff edge as visitors look out over kilometres of farmland, the CN Tower faintly visible on the horizon. Hikers can wander into the former mine pit and have lunch at a picnic table at the bottom.

“Simply walking through the Mount Nemo Conservation Area is a joy,” said Roger Goulet, the executive director of Protecting Rural Escarpment Land (PERL), a Burlington-based group that Harmer co-founded.

“The trees, the rocks, the plants, it’s amazing. It is a church.”

Nelson’s existing quarry and the lands the company is seeking to expand onto are just down the road. It doesn’t encroach on the conservation area, but the land is all covered by the UNESCO designation.

The last time the company attempted to expand the quarry, it planned to use lands only to the south of the existing pit, onto an area that neighbours the Harmer family’s land.

As part of the last application process, an archeological survey also found evidence of a pre-contact Attawandaron settlement there, dating back to the early 1600s. (At the time, the Ontario Ministry of Culture concluded that it had “no further concerns” about archeological sites on the land.)

PERL raised funds to hire independent scientists and lawyers. The battle dragged on for eight years.

In the end, a joint review panel of local and provincial officials found Nelson’s proposal didn’t adequately safeguard Jefferson salamander habitat. The creatures were living in a series of wetlands that the company hadn’t found in its surveys of the property.

On a visit to some of the wetlands in early April, a chorus of frogs chirped and a woodpecker called as a tiny brown newt swam, nearly blending in with the muddy water. Clusters of salamander spawn were visible clinging to a stick floating on the surface — at that stage of life, the tiny eggs look like speckled jelly, and it’s difficult to tell if they belong to Jefferson salamanders or other species.

“People think to themselves, ‘Salamanders? Who cares,’” Harmer said. But amphibians are an indicator species, she added, which means they reflect the overall quality of the environment.

Jefferson salamanders in Ontario have declined by roughly 90 per cent in the last three decades, the province has found.

“You’ve got to take care of the whole web,” Harmer said.

The province now designates those wetlands as “provincially significant,” which means they cannot be developed.

Nelson’s new proposal would leave them intact — its planned southern extension would be 60 per cent smaller than the 2004 plan. It would also include 18 acres of “ecological enhancements” to improve the salamander habitat, Powers said.

“We have studied the area carefully and a team of independent experts agrees it would enhance, not harm, the wetlands,” Powers said.

The western extension would go onto what’s currently a golf course. If the application is approved, the company would seek permission to extract an upper limit of two million tonnes per year, though Nelson said it would likely only take half of that on average.

Review panel has pointed to gaps in application

The proposal is still in the early stages of review by various governments and agencies, including the Niagara Escarpment Commission, City of Burlington and Region of Halton.

All three have responded so far with objection letters. Those letters aren’t a rejection, but begin a back and forth process, giving the company a chance to respond.

In a December 2020 letter, the escarpment commission outlined a series of information gaps. Among them: that the company had not looked at the cumulative impact the quarry could have on groundwater, had not accounted for the connectivity of the area’s waterways, and had not consulted with Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe communities whose traditional territory includes the plateau.

Powers said Nelson has reviewed the objection letters and plans to respond. He also says the company now has 20 years of experience studying the area and has hired more than a dozen teams of experts.

To examine the unpredictable bedrock, for example, Nelson brought in the same team of hydrogeologists that Halton Region used to map its groundwater.

“We believe we have a very thorough understanding of the landscape’s key features,” Powers said. “The review process for quarries in Ontario is one of the most rigorous in the world, and it is meant to uncover any gaps in our understanding and make us account for them.”

Some, like Burlington resident John Doyle, trust the company’s assessment. (Doyle has worked as an adviser to quarry companies, and said he had dealings with Nelson roughly 30 years ago).

“Industry knows how to manage it to tight environmental standards,” he said in a phone interview. “I get concerned that the issue just becomes ‘not in my backyard.’”

Other residents are less confident in the company’s assurances.

Elaine Saric — who is involved with a new group opposing the expanded quarry, Conserving Our Rural Ecosystems (CORE) — settled on Mount Nemo in 2015 to build her dream home. Quarries, with their dust, blasting noise and constant flow of trucks, can be a difficult neighbour. But she and her husband were ready to accept having it a certain distance away.

“Never would we have thought that it would come so much closer to us,” she said. She worries her well might dry up or become contaminated.

Saric has also heard reports of quarry blasts causing windows and drywall to crack on houses closer to the operation. Once, a crack on the wall of the Harmer family home that had been fixed opened up again after a blast, Harmer told National Observer.

Powers said Nelson has not been responsible for wells going dry in the area, and the company hasn’t received any formal complaints about vibrations from the quarry causing damage. Nelson’s office is near the edge of the quarry, and that building has never experienced cracks, he added.

‘Quarry licences are forever’

One major point of contention in Nelson’s proposal is what will be done with the land once the quarry is done.

Nelson has proposed to mine it for 30 years, then turn the site into a massive 944-acre park, twice the size of Toronto’s High Park. Renderings posted on a company-run website show a crowded beach, kayakers on a lake, and families walking and biking.

“It will become a green space for the city and the region to enjoy,” Powers said.

City officials have been less than enthusiastic.

“Quarry licences are forever,” Nisan said. “It might not happen in the lifetime of myself and yourself.”

Rehabilitating an old quarry site takes a long time, he said, and it doesn’t work in every case. Someone would have to foot the costs of creating such a park, he added.

In an interview, Burlington Mayor Marianne Meed Ward pointed out that the application in front of council is for a quarry, not a park. Council will make a decision based on the merits of the quarry plan, she added.

“That’s not what’s being discussed right now,” she said, referring to the park idea.

Powers said Nelson is willing to enter legal agreements dictating when the land would be turned over for the potential park. It is searching for a park design and operation partner, he added, and would be prepared to hand over a parcel of land “immediately,” with other pieces to be given 10 and 30 years from now.

“Any quarry application in Ontario has to include detailed information about its rehabilitation and end-use,” Powers said. “In this case, the end-use is a park, and as part of the application, it has to be considered.”

Frizzle said he’s behind the park plan.

“I think that’s a tremendous idea,” he said of the proposed park. “I’m astonished that it’s dismissed outright by some people.”

Gord Pinard, a director of CORE, said it’s an “interesting concept,” but that’s all.

“I think there's so many unanswered questions,” he said. “Right now, it's a colossal hole in the ground, compared against some really attractive pictures (of a park). And there is no clear path to get from one to the other.”

If Nelson’s application is approved, the quarry expansion would operate for 30 years. If not, Powers said, the company will continue work on its current site for at least five decades, after which it’s expected to run out of aggregate.

The escarpment commission is accepting comment on the project until April 26, but there will be more opportunities for public feedback as the application moves through layers of approvals.

Since Nelson’s last application took many years, Harmer said they’re getting ready for a long fight. This time, CORE is leading the charge and is fundraising to hire experts, just like PERL did last time.

Instead of building new quarries on the escarpment, Ontario cities should focus on using recycled aggregate for new projects and, when needed, sourcing fresh product from less ecologically-sensitive places, Harmer said.

“I have been a touring musician, I've used up a lot of roads, I understand that,” Harmer said.

“(But) do we need, in the case of Mount Nemo, to go into our best remaining natural ecosystems to mine the most homogenous gravel? It’s a world biosphere reserve, and it belongs to everybody.”

Comments

Sourcing "virgin" aggregate should be a felony - as long as there is construction waste from wrecking sites filling up landfills and being dumped helter skelter in the counrtyside. Ontario has a disastrous failure to recycle old concrete and other building waste. Pull up your shabby socks Ontario!