Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This story was originally published by Wired and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration

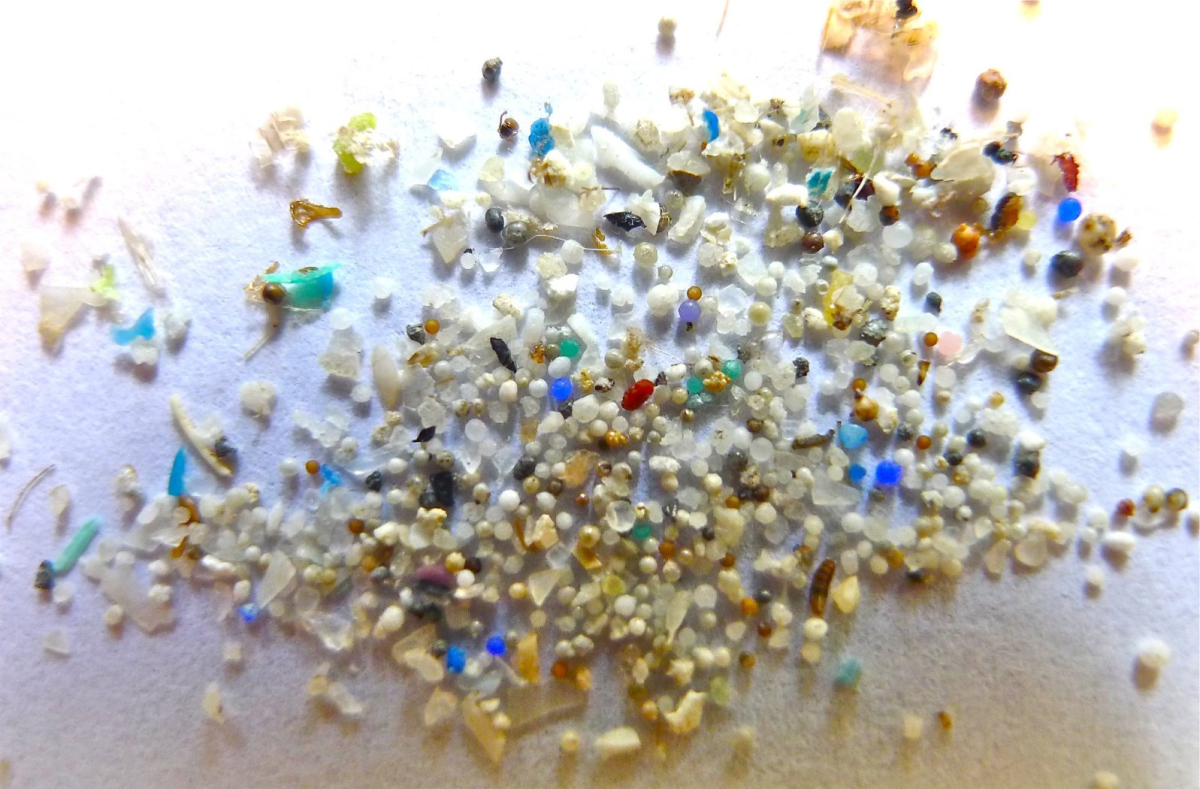

If you find yourself in some secluded spot in the American West — maybe Yellowstone or the deserts of Utah or the forests of Oregon — take a deep breath and get some fresh air along with some microplastic. According to new modelling, 1,100 tons of it is currently floating above the western U.S. The stuff is falling out of the sky, tainting the most remote corners of North America — and the world. As I’ve said before, plastic rain is the new acid rain.

But where is it all coming from? You’d think it’d be arising from nearby cities — western metropolises like Denver and Salt Lake City. But new modelling published earlier this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that 84 per cent of airborne microplastics in the American West actually come from the roads outside of major cities. Another 11 per cent could be blowing all the way in from the ocean. (The researchers who built the model reckon that microplastic particles stay airborne for nearly a week, and that’s more than enough time for them to cross continents and oceans.)

Microplastics — particles smaller than five millimetres — come from a number of sources. Plastic bags and bottles released into the environment break down into smaller and smaller bits. Your washing machine is another major source: When you launder synthetic clothing, tiny microfibres slough off and get flushed to a wastewater treatment plant. That facility filters out some of the microfibres, trapping them in “sludge,” the treated human waste that’s then applied to agricultural fields as fertilizer. That loads the soil with microplastic. A wastewater plant will then flush the remaining microfibres out to sea in the treated water. This has been happening for decades, and because plastics disintegrate but don’t ever really disappear, the amount in the ocean has been skyrocketing.

In fact, this new research shows there may now be more microplastic blowing out of the ocean at any given time than there is going into it. Put another way: So much has accumulated in the ocean that the land may now be a net importer of microplastic from the sea. “That's really highlighting the role of legacy pollution,” says Janice Brahney, an environmental scientist at Utah State University and co-lead author of the new PNAS paper. “The amount of plastics that are in our ocean is just overwhelming compared to anything that we produce in any given year in the terrestrial environment.”

These microplastics aren’t just washing ashore and accumulating on beaches. When waves crash and winds scour the ocean, they launch seawater droplets into the air. These obviously contain salt, but also organic matter and microplastics. “Then the water evaporates, and you're left just with the aerosols,” or tiny floating bits of particulate matter, says Cornell University researcher Natalie Mahowald, who co-led the work with Brahney. “Classically, we atmospheric scientists have always known that there are sea salts coming in this way,” she continues. But last year, another group of researchers demonstrated this phenomenon with microplastics, showing that they turn up in sea breezes.

This time, Mahowald and Brahney thought bigger, using atmospheric models to show how far marine microplastics might travel after they take to the air. They also looked at other sources of microplastic emissions, like roads, cities and agricultural fields. They knew, for instance, how much dust is generated from fields and how much microplastic might be in that dust.

The researchers then combined this atmospheric modelling with real-world data. Brahney used air samplers scattered in remote locations throughout the American West, so at a given time she could say how many plastic particles had fallen out of the sky. Mahowald’s modelling could also say what the atmospheric and climate conditions were like at that time, allowing the researchers to trace where the particles had likely blown in from.

They found that agricultural dust only provided five per cent of atmospheric microplastics in the West. And surprisingly, cities supplied only 0.4 per cent. “If you were to ask anyone how plastics are getting into the atmosphere, they would say from urban centres,” says Brahney. “I like to think of it more as the roads that are leaving the cities that are the most important.”

When a car rolls down a road, tiny flecks fly off its tires as part of normal wear and tear. This material isn’t pure rubber; it contains added synthetic rubbers and a slew of other chemicals. Tire particles, then, are technically microplastics, and they’re all over the place. One study in 2019 calculated that seven trillion microplastics wash into San Francisco Bay each year, most of it from tires.

Cities actually do produce an astonishing amount of microplastic through road traffic and from litter breaking apart, but it doesn’t seem to get high into the atmosphere. That’s for two reasons, Brahney and Mahowald think: Buildings block the wind from scrubbing the surfaces of a city and propelling those bits away, and people drive cars slower in metro areas, so there’s less agitation of tire particles that end up on the roadway. But get out onto the interstate highways and there’s a lot more open space where winds can whip up debris. Plus, says Mahowald, “cars are moving at 60 miles an hour. That's a lot of energy. And little tiny particles can get in the atmosphere with that energy.”

But why did these scientists go through all the trouble of modelling the extreme complexities of the atmosphere, instead of just looking at the characteristics of the microplastics that landed in their traps to figure out where they originated? The sad reality is that these plastics have so thoroughly saturated the environment that, in a sense, they’ve homogenized. Particles from synthetic clothing and from degrading bottles and packaging seem to be moving between the air, land and sea with such regularity — and enough intermixing — that it’s hard to pinpoint the source of a particular polymer.

“It's not quite hard — it's nearly impossible,” says University of Strathclyde microplastic researcher Deonie Allen, who wasn’t involved with this new research. (She coauthored last year’s study that documented microplastics in sea breezes.) “If you model it, you can figure out potentially where it might come from. But if you just look at the chemical signature of the types of plastics you've got in your bucket or in your filter, there's no way for you to tell where they may have come from.” Maybe if you can identify a piece of rubber, there's a good chance it came from a tire. “But the rest of them,” Allen adds, “they could come from anywhere.”

That’s why atmospheric modelling is critical to better understanding how microplastics are moving between environments. Researchers are just beginning to do this — there have been only a few dozen papers so far. Yet scientists need way more data on how much plastic is falling out of the sky, and where. This new research, for instance, concentrated on the American West, but the generation and distribution of particles might work differently elsewhere. The Western states are quite dry, so maybe it’s easier for cars to kick up microplastics there than it is in the soggy South. Also, in Europe, waste plastic is often incorporated into roads as a construction material, which is a noble idea, but it may mean that those roads shed even more plastics, mixing with the ones from tires.

But bit by bit, researchers are developing a clearer picture of how these particles are cycling all over the planet. A major driver appears to be the atmospheric transport detailed in this new research. “We live on a ball inside a bubble,” says University of Strathclyde microplastic researcher Steve Allen, who wasn’t involved in the research. (He and Deonie Allen are spouses.) “There's no borders, there's no edges. And this is clearly showing that microplastic is going into the sea and back out of the sea. It's raining on the land and then getting blown back up into the air again, to move somewhere else. There's no stopping it once it's out.”

“It could just be moving around the surface of the Earth endlessly,” agrees Brahney. “That's just really horrifying to think about.”

Comments