Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Canada's continent-spanning forest used to remove massive amounts of CO2 from the air each year. It was a hugely valuable "carbon sink", slowing the pace of climate change and benefiting our logging industry.

But that carbon sink has steadily collapsed to the point where the forest now emits CO2. That adds fuel to our accelerating climate crisis, and spells trouble for Canadian logging.

That is the grim story told by the data in Canada's latest National Inventory Report (NIR).

I've dug into that data to create a series of charts that illustrate what's happening in Canada's managed forest, and what it means for our climate emergency and our logging industry.

Out of thin air …

Canada's managed forest contains trillions of trees, from tiny seedlings to towering old-growth survivors. All these trees literally build themselves out of thin air. Half their weight is the carbon they pulled, molecule by molecule, from CO2 in the air.

That carbon is temporarily locked up in trees until the wood gets burned or rots. At that point, the carbon gets recombined with oxygen and released back into the atmosphere as CO2.

The balance between new growth versus fire and decay determines whether a forest is a net CO2 sink or a net CO2 emitter. In the past, our managed forest grew more than it burned or decayed — creating a giant carbon sink.

… and now back into it

But like so many of the planet's great ecosystems, Canada's managed forest is suffering from aggressive land use combined with human-created climate impacts — surging wildfires, insect outbreaks, droughts, diseases and storms.

Over the last two decades, the once great carbon sink has steadily drained away. It's now gone, and the balance in the forest has tipped to emitting CO2 instead.

And that's before accounting for the additional CO2 emitted by harvesting wood, which adds even more CO2 to the total. The logging industry benefited when the forests were a healthy carbon sink. The trees cleaned up the CO2 created by logging, and at no cost. Now this free service is gone, leaving the industry in uncharted waters.

Collapse

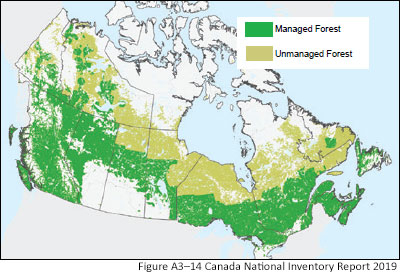

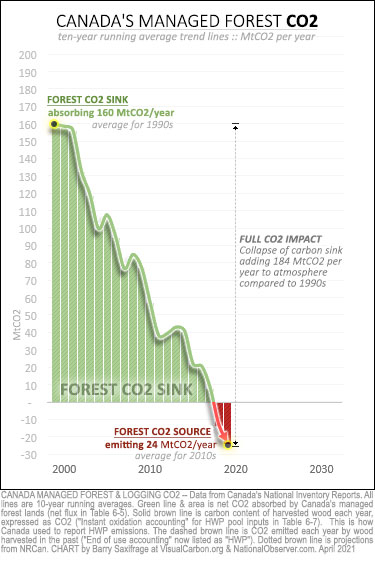

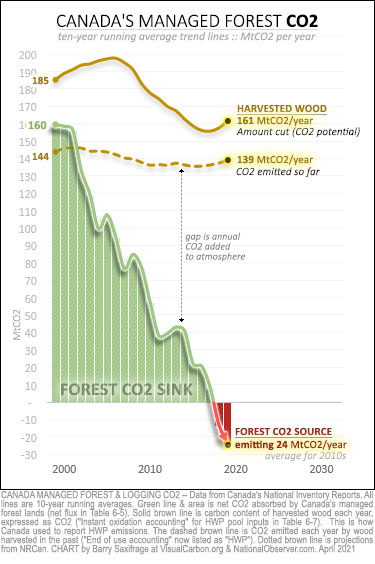

You can see the startling collapse of the carbon sink in my first chart. That plunging green line shows the net amount of CO2 that Canada's managed forest removed from the atmosphere each year. Canada reports this under the techno-speak term "net flux" (NIR table 6-5). I've plotted the 10-year running average to reveal the underlying long-term trend; each point on the line is the average of the 10 years leading up to it.

I've plotted the 10-year running average to reveal the underlying long-term trend; each point on the line is the average of the 10 years leading up to it.

For example, that upper left dot means that during the 1990s, Canada's managed forest removed an average of 160 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) per year from the atmosphere. That added up to 1,600 MtCO2 over the decade. It was a huge help in the climate fight — and a huge free service for our logging industry.

The tipping point occurred when the green line plunged past zero and turned red. That's when the balance for the preceding 10 years flipped to being a net source of CO2, instead of a sink.

And that final dot, in 2019, means our faltering managed forest released an average of 24 MtCO2 per year into the atmosphere during the 2010s.

The full impact in the atmosphere

As my next chart shows, the full climate impact of this lost carbon sink added up to 184 MtCO2 per year, on average, during the 2010s.

That's the increase in atmospheric CO2 compared to what it would have been if the forest carbon sink had remained healthy at 1990s levels.

For scale, that's five tonnes of CO2 per Canadian per year — double the emissions from all our passenger cars and trucks.

Such a huge new flood of CO2 into our already destabilized climate is obviously bad news.

It's bad news for our forest.

It's bad news for our climate.

It's bad news for Canada's plans to use forest "offsets" to green-light extra fossil fuel burning.

And it's bad news for our logging industry's plans to continue selling their wood as a climate-safe and climate-sustainable carbon product.

Two billion more trees

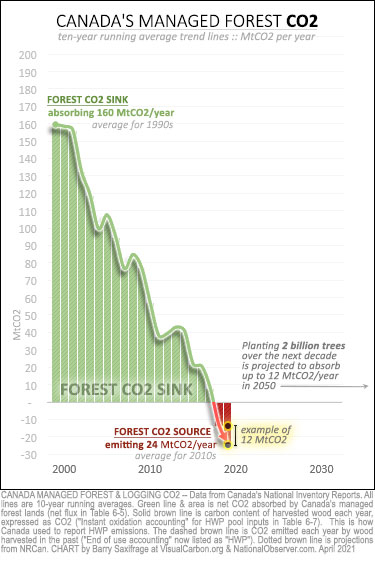

In an effort to bolster the collapsing carbon sink, Ottawa announced a "Two Billion Trees" initiative.

The government plans to spend $3.16 billion over the next decade to plant an additional two billion seedlings. This would be a 40 per cent increase in the number of seedlings planted in Canada.

If all goes well — which they say will be challenging because of rising climate impacts — these new trees could remove as much as 12 MtCO2 per year by 2050.

While that would be welcome, it pales in comparison to the scale and pace of the problem.

I've added a tiny bar at the bottom of the chart to show what 12 MtCO2 looks like. It’s roughly the amount that has been disappearing every 16 months since the 1990s.

And, most troubling for our forest and for us, there is no sign it will recover until humans bring our metastasizing climate crisis under control.

Climate changing 10 to 100 times faster than forests can adapt

To get a sense of what's coming, here's what National Resources Canada says in the latest State of Canada's Forests report :

"Scientists predict that increasing temperatures and changes in weather patterns associated with climate change will drastically affect Canada’s forests in the near future. With the rate of projected climate change expected to be 10 to 100 times faster than the ability of forests to adapt naturally."

And in one of the most depressing climate warnings I've read recently, the report goes on to say that naturally reseeded forests are expected to struggle under climate change:

"(Local seedlings used to be) best adapted to the climate conditions of the site. However, with a rapidly changing climate, these local populations may not be able to adapt quickly enough, and while well-established adult trees can often withstand increased stress, seedlings are highly vulnerable. "

Canadian forestry scientists are so concerned, they are turning to "genomic selection" in a race to develop seedlings that might be better able to survive. This effort combines a suite of computer analysis, DNA-sequencing, rapid propagation, and cross-breeding techniques they hope will produce seedlings that can handle the rapidly shifting climate we are cooking up. Then humans will need to plant these seedlings in the right places.

This reminds me of the frantic race by coral scientists and coral CRISPR engineers to develop "super corals" that won't all just die in our increasingly overheated and acidified oceans. They, too, will need to plant their coral seedlings in the right places and on a mind-boggling scale.

As Elizabeth Kolbert documents in her excellent new book, Under A White Sky, The Nature of the Future, the growing number of technological "interventions like assisted evolution and gene drives" are no longer seen by the scientists leading them as techno-optimistic improvements of the originals. They are just the best anyone has come up with to "prevent no-longer-fully-natural ecosystems from collapsing."

So far, we've looked at the collapse unfolding in Canada's managed forest. Now let's take a look at the additional CO2 being released by logging.

Logging from CO2-emitting forests

Forestry and wood products are advertised as good for the climate on the theory the CO2 emitted by logged wood gets reabsorbed by new growth.

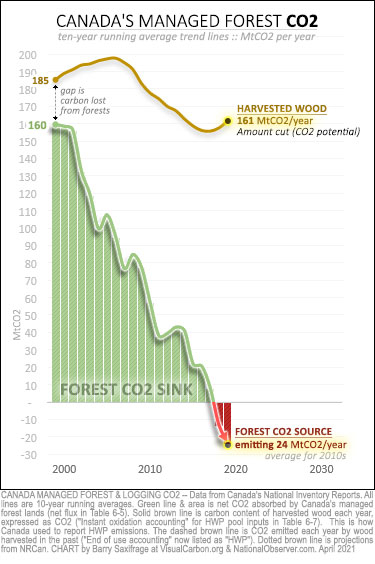

But, as we've seen, the government data shows Canada's managed forest isn't absorbing CO2 anymore — it's emitting it. My next chart lets you see what this means for logging.

I've added a solid brown line, which shows the carbon content of the wood logged and removed from the forests each year. And I've used a 10-year running average for it. (Note: You can find this data listed in NIR Table 6-7 as "inputs to carbon stocks".)

Now, compare that harvested wood line to the green line showing how much carbon the forest was absorbing.

Until the 2000s, the forest almost kept pace with logging. The gap between the amount of carbon that logging took out and the amount the forest replaced was relatively small.

But as the forest carbon sink collapsed, less and less got replaced.

Over the last decade, as Canada's managed forest flipped to be a carbon source, it couldn't replace any of the carbon that logging removed from it. We have been logging a forest that is already a net emitter of CO2.

The growing flood of CO2 into the atmosphere

All that harvested wood doesn't instantly turn to CO2. There is a delay between the time when a tree is cut and when its carbon turns into CO2.

In Canada, most harvested wood reverts to CO2 within a few years. Very roughly, one-third is burned for energy. Another third is made into short-lived products, like paper, that are discarded and rot within a few years. The final third, is made into longer-lasting wood products, like building materials and furniture, which can take up to several decades before reverting to CO2.

Canada tracks and reports how much of the carbon stored in harvested wood was emitted as CO2 each year. That's the lower dashed brown line I've added to the chart.

You can find this data in the NIR's top-level inventory table, listed under "HWP" (Harvested Wood Product). And I've again used a 10-year running average for it.

If you look at the left of this dashed line, you'll see that harvested wood emitted an average of 144 MtCO2 per year before 2000. But the green line shows the forest back then absorbed even more than that: 160 MtCO2 per year.

Having the forest absorb more CO2 than the harvested wood emitted made it easier to argue that the wood was "carbon neutral".

But as the forest carbon sink collapsed, the forest couldn't keep up.

A gap opened between that plunging green line and the steady, business-as-usual-logging dashed brown line. The size of that gap shows how much CO2 was being added to the atmosphere.

What started as a trickle in the early 2000s, quickly turned into the flood. And during the last decade, Canada's managed forest didn't absorb any of the CO2 emitted by the wood harvested from it. That's because, again, our managed forest ended up being a net emitter of CO2 over that decade.

Twenty years ago, all the CO2 being emitted by harvested wood was being taken back up by the forest. Now none of it is. Instead, it is accumulating in our atmosphere, worsening the climate crisis.

Killing the golden goose

This highlights one of the many economic threats created by foot-dragging on climate action. As our intensifying climate impacts drive ecosystems to become CO2 emitters, these degraded ecosystems no longer provide us with the valuable free service of cleaning up our CO2 mess.

Canada's logging industry, in particular, reaped the benefits of this free CO2 removal. The carbon they harvest from the forest is exempted from Canada's carbon tax and from Canada's climate pollution targets. And their wood products have been viewed as "carbon neutral", giving them a marketplace advantage over alternatives that lack a free CO2 cleanup.

It was certainly a great deal, while it lasted.

To appreciate just how good it was, consider that a company like Climeworks, in Iceland, currently charges $1,000 per tonne to extract CO2 from the air with technology and store it safely away. To hire Climeworks to do the job the forest used to do for free would cost more than $100 billion a year.

The climate science is crystal clear: To prevent a full-blown climate crisis, all our CO2 emissions must quickly fall to a net of zero. Any CO2 we emit must be balanced by physically removing an equal amount from the atmosphere.

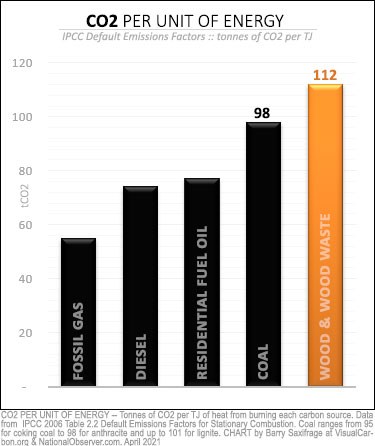

The climate doesn't care if the excess CO2 piling up in the atmosphere comes from ancient plants, like coal, or from living ones, like logged wood.

In fact, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says burning wood is even more climate polluting than burning coal, per unit of heat.

As noted above, roughly a third of the wood logged in Canada gets burned for fuel. And now that form of carbon fuel is coming from a forest without a net carbon sink to offset it.

Given the rising pressure on governments and businesses to shut down all our excess CO2 emissions, I imagine it will become increasingly difficult to convince the customers of Canadian wood that logging from a CO2-emitting forest is a climate-safe and climate-sustainable choice.

There was a time when optimists argued that Canada's forest would be a global warming winner. Their hope was that warmer temperatures and extra "CO2 fertilization" would lead to increased growth. But whatever benefits those brought are being overwhelmed by the downsides of climate change: increasing fire, death and decay.

The late, great climate scientist Wallace S. Broecker repeatedly warned the Earth's history reveals that ''the climate system is an angry beast and we are poking it with sticks.''

After decades of recklessly poking at it with ever-larger sticks, that angry beast is now rampaging its way ever deeper into our ecosystems and economy.

Comments

"One of Canada’s biggest carbon sinks is circling the drain"

NRCAn's graph "Net carbon emissions in Canada's managed forests: All areas, 1991 to 2018" tells a very different story. The rise in forest emissions since the turn of the millennium is dramatic.

https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/our-natural-resources/forests-forestry/state-ca…

Hard to ignore the discrepancy. Any explanations?

A 10-year running average smooths the data out, but it cannot hide the steady rise in forest emissions over the last two decades.

According to NRCAn, Canada's managed forests have been a net carbon SOURCE since 2001. Not a net sink. Adding to our man-made totals, not subtracting.

NRCan: "Net carbon emissions in Canada's managed forest: All areas, 1990–2015"

Going back to 1991, Canada's managed forests were carbon sinks in 9 of those 11 years up to 2002, and the amount they absorbed was modest.

Average carbon removal from 1991 to 2001 was 24 Mt. On par with 2019 emissions from Newfoundland and New Brunswick.

At no time (in NRCan's dataset) did Canada's managed forests come close to matching Canada's man-made emissions.

Canada's creative accounting:

"Canada's forests actually emit more carbon than they absorb — despite what you've heard on Facebook" (CBC, Feb 12, 2019)

"Our managed forest land hasn't been a net carbon sink since 2001

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/canada-forests-carbon-sink-or-so…

"In its 2017 revised submission to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the federal government indicated how it plans to re-evaluate its accounting of biomass.

"'Canada is examining its approach to accounting in the land use, land-use change and forestry sector,' the submission reads.

"As part of this process, CANADA WILL 'EXCLUDE THE IMPACTS OF NATURAL DISTURBANCES AND FOCUS ON ANTHROPOGENIC EMISSIONS AND REMOVALS.'

"In other words: Don't count our wildfires or the devastation from our pine beetles, but do count our forestry and farming practices.

"This approach, [Mark Cameron, Canadians for Clean Prosperity, and former policy adviser to PM Stephen Harper] says, would go a long way toward helping Canada meet its emission-reduction targets under the Paris Agreement.

"'By switching to one of the alternative accounting methodologies for emissions from land use, forestry and forest products allowed under the framework, Canada could narrow the gap — perhaps by as much as 63 or 126 megatonnes — even if our actual emissions don't change.'"

So Canada will exclude the emissions caused by AGW (anthropogenic global warming) impacts (wildfire and insect infestations), which make Canada's managed forests net carbon sources.

In the real world, Canada's forests will increasingly be net carbon sources.

Env Minister Catherine McKenna's shifty accountants turn a net carbon source into a carbon sink.

Magic.

These are good points about (a) Canada deciding to exclude human-caused climate impacts and (b) that they also changed the bookkeeping in other ways. Readers wanting a deep dive into the changes Ottawa has made to forest carbon can try my in-depth explainer on this "As Canada's Forests become carbon bombs, Ottawa pushes the crisis off the books": https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/03/30/opinion/canadas-forests-bec…

The NRCan graph that you link to, Geoffrey, is a combination of the forest "net flux" and "HWP".

My article and chart breaks this one value down into the two components, so people can see the role played by each.

The green line in my chart is the "net flux" of forest primary productivity. That's before accounting for logging. This is important to look at separately, in my view, because it shows the forests are emitting CO2 even before accounting for logging. This shows the failing health of the forest itself.

The dashed brown line in my chart is the second part -- the additional CO2 from harvested wood. By showing this separately, readers can see the specific impact of this.

In the last of my charts, the gap between those two lines is the same as the "net emissions" line in the NRCan chart you link to.

We're well and truly cooked. There's no turning this around.

Misleading headlines offend me, and the oft-repeated assertion that "Canada's forests ... are now net emitters of carbon" is one example; on its own, that statement makes it sound as if forests, actual standing old-growth (or old second-growth) forests, are now a climate liability and should be eliminated from the landscape as fast as possible. But that is what we're doing -- cutting them down, burning them, clearing the land -- it is NOT the forests that are emitting carbon; it's our over-harvesting, and all our fossil-fuel dependency fueling climate change, that is emitting carbon. The forests are not the problem. We are the forests' problem. We are the principal problem of every living thing on earth.

One third of harvested wood is used for fuel? Is that wood that has other uses (lumber, paper), or is it from what is often referred to as 'trash wood' left over from commercial timber harvest? Not sure that logged wood is used much as heat anymore, but pellets certainly are.