Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

In April, Ocean Wise, the non-profit conservation organization struggling to shepherd the Vancouver Aquarium through the pandemic, admitted defeat and sold to a private company, Herschend Enterprises. Herschend, an American theme-park corporation that already owns two aquariums, says it will be business as usual when the doors once again open to the public.

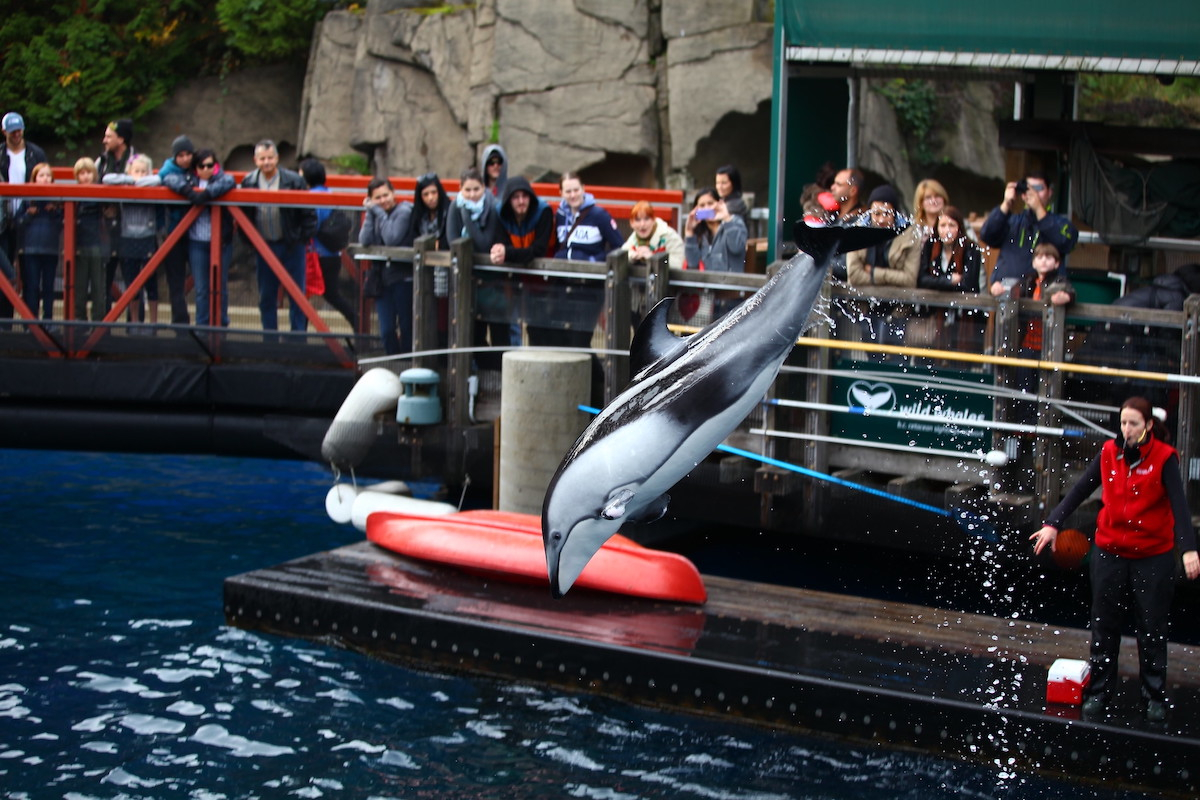

For now, that entails maintaining and displaying the 70,000 animals currently housed in the aquarium, including sea otters, sloths, a green sea turtle, harbour seals, African penguins and Helen, a Pacific white-sided dolphin. Herschend has said the company will take the first two years “listening and learning” before making any changes to the renowned institution. A survey is circulating, says Herschend’s executive director, Eric Rose, to gather public input: “What are Vancouverites wanting to see? Is there a wish list? Is there something Vancouver did in the past that you’d want us to bring back?”

But the tides are turning in terms of public perception of holding animals in captivity, both in Canada and abroad. For animal rights activists like Annelise Sorg, president of the non-profit organization No Whales in Captivity, the future of the Vancouver Aquarium lies not in bringing certain exhibitions back but in banning most animals from display altogether.

Though her organization primarily focuses on cetaceans, Sorg says she’s willing to consider joining other groups such as the Vancouver Humane Society to pressure the Vancouver Aquarium to give up live displays.

“I think the public is ready to consider not having animals in captivity — especially mammals, and especially when there are so many alternatives,” said Sorg. When No Whales in Captivity first began petitioning the Vancouver Park Board to end the captivity and display of cetaceans at the Vancouver Aquarium in 1992, there wasn’t much support. However, in the years that followed — the past five years in particular — the movement to ban the captivity of animals for display has picked up considerable momentum.

In 2017, the Vancouver Park Board voted to prevent the Vancouver Aquarium from bringing new whales and dolphins into captivity. Vancouver Aquarium’s CEO at the time, John Nightingale, initially pushed back against the decision before eventually acquiescing in 2018.

Then, in 2019, the federal government went to bat for the animals. The Senate passed Bill S-203, which legislated the ban on any facility acquiring new cetaceans for purposes other than rehabilitation or if deemed in the best interest of the animal’s welfare by the lieutenant-governor in council. The bill was introduced in 2015 by then-Sen. Wilfred Moore and sponsored by former senator Murray Sinclair when Moore retired. “I supported the bill mainly because I believed that holding large cetaceans was contrary to their best interest,” said Sinclair.

Before retiring himself this January, Sinclair also put forth Bill S-218, otherwise known as the Jane Goodall Act. “(The act) basically takes the principles of S-203 and makes it applicable to large creatures, like great apes and elephants — to ban their captivity and ban their being brought into the country for the purposes of being put on display.” Though the act specifies elephants and primates, Sinclair says there is a clause that would allow the government to add other large animals as it sees fit — possibly even seals and sloths, two species currently held at the Vancouver Aquarium.

Sinclair, however, doesn’t view these bills as total bans, nor does he think their existence implies the impending obsolescence of aquariums. “(Zoos and aquariums) have a valid reason to exist, and we shouldn’t denounce them simply for holding animals in captivity because there are some valid reasons for having animals in captivity.” Protecting species from extinction due to habitat degradation, caring for animals already born and bred in captivity and fostering injured animals might warrant exceptions to anti-captivity legislation, Sinclair says.

Nonetheless, Sinclair suggests aquariums ought to rethink their purpose, goals and infrastructure. “Those that are going to continue in existence now have to comply with a new set of regulations, and so they have to ensure that facility that they run properly houses the animals they’re holding in captivity,” said Sinclair. “I suspect that there will be a significant change in the way that these organizations operate, and if there isn’t then they will be shut down.”

According to marine biologist Hal Whitehead, who defended Bill S-203 in court, a positive change would be scaling down the size of animals considered for placement in aquariums. Whitehead believes aquariums can successfully simulate an environment that is not too dissimilar from the natural habitat of smaller aquatic animals, like snails, mussels and even squid. Eliminating the larger species, he says, would also help patrons appreciate their smaller counterparts better. “(For) terrestrial zoos, I can see maybe scorpions and snakes,” said Whitehead. “People can go around and look at them, and they’re not immediately rushing off to see the elephants because there isn’t an elephant.”

But with operational fees that cost up to a million dollars a month, could the Vancouver Aquarium survive financially without some of its larger animals to lure in tourists? Sorg thinks so. “When we got the orcas out, the aquarium whined and whined that they couldn’t make it without the orca; then they whined and whined that they couldn’t make it without the belugas… the point is that their business model is completely antiquated,” said Sorg. Following the introduction of Bill S-203, the Vancouver Aquarium claimed a 13 per cent dip in attendance but remained profitable until the pandemic. “If they had little green men running, people would go see it,” said Sorg. “It just doesn’t matter what they have there as long as it’s quality entertainment.”

Rose says Herschend will absolutely comply with any regulation that’s put in place. “We will always respect the laws and not take a confrontational approach.”

Yet he firmly believes in the power of live displays and aquariums’ ability to manage them. “I was inspired by the animals in Baltimore, and in zoos and aquariums — well-run zoos and aquariums — any animal can be taken care of properly under the right circumstance.” But Rose also acknowledges that change in the industry is inevitable. “I’ve been doing this for 30 years, and the practices I started with 30 years ago are very different today,” he said. “I would venture to say the standards 30 years from now are going to be very different from where they are today.”

To someone like Whitehead, the current and ongoing transformations in aquariums represent a more just society: “Part of that trend is that we start to treat sentient beings in the rest of the world a bit better than we used to.”

Comments

No data on this public opinion that's allegedly changing. I don't even recall seeing a survey on the most-fraught topic of cetaceans when that was banned.

I've always had a soft spot for the Vancouver Aquarium because I thought of it as ours. Run by a local nonprofit and, in a way, the Vancouver Park Board, I felt like there was some kind of commitment to science, and the whole thing was consistent with the concept of being humane, and there was definitely that feeling that it was part of my community. So if there were problems, if there were issues, I wanted to work with the aquarium to find ways that it could keep doing its thing while at the same time being ethical and responding to people's values.

But if it's gonna be owned by a foreign corporation, I won't feel there's anyone I can trust to work with, and I won't give a flip if they go out of business. The city of Vancouver should have stepped in--bailed out the non-profit, taken it over themselves, something, not sold it to some American corporate bastards.

No question in my mind that there should be limits on animals held in captivity, but zoos provide a healthy and educational form of entertainment for our citizens, and especially for our youth. I think it is also important for people to connect with nature and wildlife on an emotional level, and not just as a commodity to be exploited.