Decades after mercury poisoned the water, Grassy Narrows still searches for answers

Gigoo-Aakoosi: Fish Is Sick tells the story of the Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum-Anishinabek, also known as Grassy Narrows First Nation, and Wabauskang First Nation and the historical and ongoing devastation endured by those living with water contamination. Through a nationwide investigation called Clean Water, Broken Promises, led by the Institute for Investigative Journalism and in partnership with Humber College and Canada's National Observer, we examine how water issues impact Indigenous communities.

In Part 1, we examined the history of the pollution in the English-Wabigoon river system caused by the Dryden paper mill.

In Part 2, we told the story of Wabauskang First Nation and its desire for compensation for water contamination.

In this story, we continue speaking to people whose voices are rarely heard in the media about the very early days of mercury contamination and its multi-generational impacts in Asubpeeschoseewagong.

At the age of 8, Brenda Kokokopenace of Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum-Anishinabek (also known as Grassy Narrows First Nation) in Ontario remembers the earliest conversations she had about the water.

“My sister started to complain that the water was tasting real bad,” said Kokokopenace, 65, about her conversation with her older sister, Jessie Assin.

Assin started to complain as early as 1964 about water that came from the Dryden area.

Between 1962 and 1970, 10 tonnes of untreated mercury were discharged from the chlor-alkali plant next to the Dryden pulp mill, polluting the English-Wabigoon river system for hundreds of kilometres. Known as one of Canada’s environmental catastrophes, it caused irreparable damage to aquatic, animal and human life. Several Indigenous communities living along the waterways were largely impacted, such as the Asubpeeschoseewagong people and Wabaseemoong First Nation, approximately 100 kilometres northeast of Kenora, Ont.

The mercury dump became well publicized in 1970.

However, our investigation uncovered a 1969 survey by the Ontario Water Resources Commission — now part of the province’s environment ministry — that concluded government officials had concerns about “gross” pollution levels entering the English-Wabigoon river system from the Dryden mill. The report also stated waste from the pulp and paper mill had started to enter the river since it opened in 1913.

“She knew it was coming from there, telling me we’re gonna be poisoned by the water,” Kokokopenace said about her sister. The environmental disaster, which contaminated the Wabigoon River with mercury from Dryden Chemicals Limited, had a lasting impact on her life and members of her community.

The report has the leadership of Asubpeeschoseewagong searching for even more answers.

“Is this something we should be looking into further?” asks Chief Randy Fobister, citing environmental racism, the well-documented suffering Indigenous, Black and racialized communities have endured at the hands of polluting industries.

“That’s what the province has been practising all along and still to this day.”

‘Heaven,’ before and after

JB Fobister remembers a time when families would come together, cook over an open fire and listen to creation stories. Because of mercury poisoning symptoms today, JB receives compensation from the Mercury Disability Board. Photo by Anushka Yadav

“You could hear the ducks chasing each other around. You could hear the birds singing,” said JB Fobister.

“If I said, you know, I want to go back to heaven, that’s the kind of heaven I’d want to live in."

Like JB’s ancestors, the Indigenous people in the region harvested fish, hunted water-bearing animals and drank from the English-Wabigoon river system. JB — a distant cousin of Randy, the Asubpeeschoseewagong chief — says the land and water was everything his family needed.

In the past, and to this day, the three communities of Asubpeeschoseewagong, Wabauskang and Quibell all had strong ties and family connections while living along the water system.

Reminiscing, JB turns more serious, remembering when life took a dark turn.

Between 1962 and 1970, 10 tonnes of untreated mercury were dumped into the Wabigoon River by Dryden Chemicals Limited, travelling downstream for 250 kilometres from the Dryden mill and reaching Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba.

According to a Mercury Disability Board report, in 1963, Asubpeeschoseewagong (or Grassy Narrows, as it was referred to in the report) was relocated, purportedly as a way to benefit from “improved roads, indoor plumbing, sewers, electricity and a new on-reserve school.” Mercury poisoning wasn’t named as a cause for the move.

In 1970, the provincial government officially announced the English-Wabigoon river system had been contaminated.

In a parliamentary debate, Liberal MP John Mercer Reid, whose Kenora riding included the First Nations in question, was outraged.

“It has only been in the past two or three months, after a great deal of pressure brought by the Indian reserves in the area, (that) the provincial government has agreed to hold an inquest into the deaths of a number of people who died under what can only be termed as unusual circumstances," he said.

“In the Kenora district, death by violence of the Indian people is one of the highest in Canada. There has been some suspicion that part of this has been caused by the buildup of the mercury in their systems.”

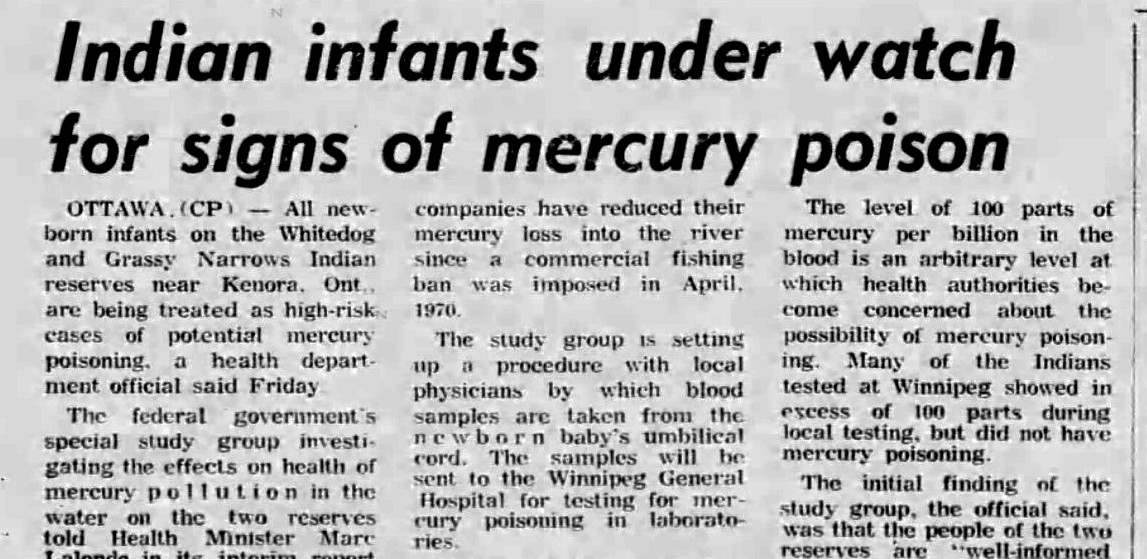

A few months later, several newspaper articles reported infants born in Asubpeeschoseewagong and Wabaseemoong were at high risk of mercury poisoning.

Kokokopenace remembers these illnesses — and deaths.

She believes the mercury-poisoned water killed her two-month-old, Freda Jane Kokokopenace, in May 1974.

Kokokopenace also had a two-year-old son at the time, Donovan, who was born with a string of health problems and spent the first six months of his life in a hospital.

Freda was always sick after she was born, explains Kokokopenace, who fed her bottles mixed with water from the Wabigoon River and canned evaporated Carnation Milk. “(We) kept taking her to the hospital.”

Like her ancestors, Kokokopenance, a soft-spoken woman who punctuates her speech with a nervous laugh, ate fish from the river, even while pregnant.

She remembers the last time she saw Freda. “She was just picked up by an ambulance, and then I was just told that she was dead,” said Kokokopenace. The doctors said she died of pneumonia.

“It was such a difficult time,” said Kokokopenace, who blames herself for Freda’s death.

As part of a federal government study during the 1970s, the Department of National Health and Welfare Canada — as Health Canada was called back then — started to collect blood and hair samples from some community members to test for methylmercury.

Roger Keesick was among those tested.

Keesick’s hair sample had methylmercury levels as high as 229.33 parts per billion (ppb) in September 1978, according to written test results his daughter, Rosemary Ashopenace, received from the federal health department. The department letter indicated levels between 0 and 20 ppb were acceptable.

Many years later, to address the mercury poisoning directly, the Asubpeeschoseewagong and Wabaseemoong people were compensated through the Grassy Narrows and Islington Indian Bands Mercury Pollution Claims Settlement Act, enacted in 1986.

The settlement led to the creation of the Mercury Disability Board, a legislated, non-profit organization meant to award financial compensation to community members. Structured on a point system, the board identified seven categories of symptoms to determine how much a community member or claimant should receive.

It became compensation for generations to come.

A multi-generational crisis

Brenda Kokokopenace sits with her 13-year-old granddaughter, Freda Jane Kokokopenace (right). In 1974, Brenda, who is from Asubpeeschoseewagong (Grassy Narrows), lost her baby, also named Freda. Brenda believes contaminated water killed her child. The elder's story is far too similar to others we heard in the Wabauskang First Nation. Photo by Martha Troian

Kokokopenace’s 13-year-old granddaughter, Freda Jane Kokokopenace, shares the same name as the daughter she lost in the spring of 1974, but that’s not all.

Both Fredas were born sick.

Illness remains common in this Ojibwe community, and people live with symptoms they believe are consistent with mercury poisoning.

Today, the community receives its water from an upgraded water treatment plant. Prior to the plant's completion last fall, Asubpeeschoseewagong was under a boil water advisory for years. Many community members, such as Kokokopenace, do not trust drinking from their taps and will sometimes opt for bottled water instead.

Freda is the daughter of Ashopenace, whose father had high methylmercury levels in 1978. Ashopenace also has a 24-year-old son, Darwin Fobister, who suffered from seizures shortly after he was born. Darwin lives with mercury poisoning symptoms, for which he receives compensation.

“My daughter was the worst one ... when she was born, she had seizures,” said Freda’s mother, Rosemary Ashopenace, referring to the mercury poisoning.

“She was always full of health problems.”

Freda is a tall and slender girl and wears her long, dark hair with an asymmetrical bang that veils her right eye.

Blind in one eye, Freda was also born with a ventricular septal defect, commonly called a “hole in the heart.”

She is non-verbal due to a hearing condition and suffers from frequent kidney infections.

Aschopenance transitions to talk about her son Darwin.

“When he was a newborn, he kept having seizures,” said Aschopenace. The seizures lasted until he was five years old.

Journalists from the investigative team met with Darwin while visiting the community to learn more.

Tall and stocky with a soft voice, Darwin remembers his last seizures.

“I had my two last ones at the age of five, and those ones almost killed me. It was pretty wicked when I was young,” said Darwin.

He also lives with a bone deformity in his left ankle, which regularly gets swollen. Darwin said it can feel like pins and needles.

As for his biggest fear: “I get scared sometimes because when I'm sleeping, I twitch and I'm scared that, you know, what if I have a seizure? … (Because) I sleep alone and I'm scared that no one will be there.”

Christine Till, an associate professor in the faculty of health at York University, studies mercury and pregnancy.

“The fetus of the unborn baby and young children are at great risk of mercury neurotoxicity, and the issue with that is, it can cause damage that’s permanent,” said Till.

This can lead to birth defects and congenital mercury poisoning, causing seizures, blindness and impaired co-ordination, among other issues.

Today, many community members continue to eat fish, just like other Indigenous communities along the river system, because it is natural for them, and it is part of an instinct, as Judy Da Silva describes it, the environmental co-ordinator and a long-standing activist in Asubpeeschoseewagong.

Tara Letwiniuk, chairperson of the Mercury Disability Board, a legislation and community-based organization that provides compensation for mercury poisoning victims, says: “All members of Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong are eligible to be assessed by the (disability board) every two years. This acknowledges the progressive nature of the impact of mercury on human health.”

From the board’s inception in 1985 to Jan. 31, 2021, of the 854 applicants, “336, or 39 per cent, have received compensation,” wrote Letwiniuk in an email statement.

Asubpeeschoseewagong has faced the restrictions and closures because of the pandemic, and Kokokopenace is waiting for the day she can get back into the classroom where she assists teaching language to the next generation of Anishinaabeg people.

She would also like to get back to working with river team researchers testing the once-clear waters her father used to guide on.

“They are hiring more than 14 people to join the river team this time,” said Kokokopenace of the remediation efforts that include collecting water, mud and fish samples from the English-Wabigoon river system.

“I don’t know if they can clean up the water,” admits Kokokopenace. But underneath her skepticism, she remains hopeful and committed.

“We still have a lot to do about the water.”

This series is part of ‘Clean Water, Broken Promises,’ a national investigation examining water issues in Indigenous communities co-ordinated by Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism and in partnership with Humber College and Canada's National Observer.

— With files from Patrick Simpson and Druv Sareen