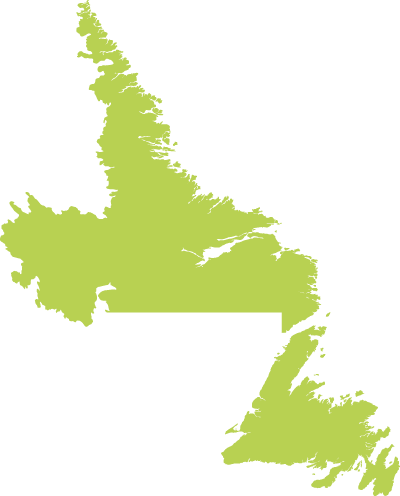

- Newfoundland and Labrador has some of the strongest winds in North America — but less installed wind generation capacity than any other province.

- The province is banking on offshore oil — a staple of the local economy — and a massive hydroelectricity project as its main energy sources, and restricting small-scale renewable plans in the process.

- City officials in St. John’s aren’t waiting on the province to lead the charge. A municipal climate plan is in the works, but the city lacks funding and expertise to get its own renewable energy initiatives off the ground.

In 2010, Nick Mercer disembarked from the ferry in Port aux Basques, N.L., to find the Trans-Canada Highway closed due to unsafe weather conditions.

It wasn’t ice or rain threatening to shove his cozy Hyundai Accent into the ditch — it was wind.

Mercer was in disbelief but would learn — through his master’s at Memorial University, his PhD in geology and environmental management at the University of Waterloo and a great deal of first-hand experience — that Newfoundland and Labrador has some of the fiercest winds in all of North America. It could go toe-to-toe with any jurisdiction in the world. This revelation brought with it a question, one that took hold of him on that first day in Port aux Basques and directed the course of his career: “How is it possible to have such a profound wind energy resource, but still be ranked last dead (dead last) in wind energy capacity?”

Newfoundland and Labrador has less installed wind generation capacity than any other Canadian province, a grand total of 54 megawatts across two wind farms. By comparison, neighbouring Nova Scotia, which has less wind to work with, has in excess of 600 megawatts of installed wind capacity.

A 2008 assessment from Memorial University concluded Newfoundland and Labrador could theoretically generate 117 times the amount of energy it consumes just from wind. And an analysis from 2016, published in the journal Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, calculated that if the province harnessed only a quarter of its high-capacity wind sites, it could power a spectacular 20 per cent of the country. And yet, only 18 turbines stand, with no more on the horizon.

Mercer decided to find out why. He conducted 17 interviews with experts from academia, community groups, government and the private sector, and published his results in the journal Energy Policy back in 2017.

It was a tale as old as time: lack of political will.

The province, he discovered, was rooted in offshore oil and terrestrial hydroelectricity, with little bandwidth for anything else. Whereas provinces like New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Prince Edward Island have all decreased their carbon emissions, Newfoundland and Labrador has seen emissions climb by 5.4 per cent since 2005 and increased its oil consumption. The Way Forward, a provincial government action plan for the next decade, committed in 2019 to cutting greenhouse gas emissions 30 per cent from 2005 levels by 2030. But Newfoundland and Labrador has missed the mark before: the same report noted the province would not achieve a 2020 emissions-reduction goal of 10 per cent below 1990 levels.

Breaking dependence on oil and gas 'mega projects'

Newfoundland and Labrador aims to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Newfoundland and Labrador is the only province in Canada without some kind of carbon-reduction legislation in place, perhaps due to the province's reliance on revenue from its plentiful oil and gas reserves.

Over the past two decades, offshore oil and gas has accounted for 25 per cent of the province’s gross domestic product and 41 per cent of its total exports, says Ken Morrissey, senior adviser for communications, research and policy with the Newfoundland and Labrador Oil & Gas Industries Association.

The industry has paid $20 billion in royalties to the province since 1997 (by far the largest industry contributor) and directly employs approximately 6,500 of its residents.

And there’s no shortage of fossil fuels yet to exploit.

According to a 2020 assessment from the international oil and gas consultancy Beicip-Franlab, there are potentially 63.3 billion barrels of oil and 224.1 trillion cubic feet of gas waiting in Newfoundland and Labrador’s offshore reserves.

“This is some of the greatest offshore resource potential in the world,” said Morrissey.

This is some of the greatest offshore resource potential in the world.

Ken Morrissey, senior adviser, Newfoundland and Labrador Oil & Gas Industries Association

In The Way Forward, former minister of natural resources Siobhan Coady writes: “The (offshore oil and gas) industry’s impact on local employment, business opportunities and government revenue has made a significant contribution to our standard of living, including the public infrastructure, programs and services we deliver to the people of Newfoundland and Labrador ... We need to foster a culture of collaboration and entrepreneurship to increase our global competitiveness, maximize economic recovery, drive innovation and supplier capabilities, and reduce the time from prospectivity to production.”

The province has embraced hydroelectricity, but while a renewable source of power, its largest endeavour comes at the expense of wind. In 2012, Newfoundland and Labrador sanctioned the controversial Muskrat Falls hydroelectric dam. This project, criticized for its potential environmental impacts and dangers posed to communities downstream, has cost the province over $13 billion. In order to secure debt financing for the project, the province had to guarantee a reliable customer base for its electricity, and so passed Bill 61, effectively restricting small-scale renewable power projects by communities and companies across the province, forcing both to buy power from Muskrat Falls rather than establishing their own renewables.

“A factor is this mega-project mentality,” said Mercer, who serves as co-chair for Decarbonize Newfoundland and Labrador, an organization that seeks a just, equitable and sustainable future for the province at large. “If it’s not a massive offshore oil rig, if it’s not an 850-megawatt hydroelectric facility, the province simply has no interest.”

An appetite for wind

Mercer speaks with the rolling vowels of his Cape Breton mother and the hasty tempo of his Newfoundland father, while also handling Inuit words like Aulatsijingita, Tuavittumik and Kattaniatumik with practised ease.

If it’s not a massive offshore oil rig, if it’s not an 850-megawatt hydroelectric facility, the province simply has no interest.

Nick Mercer, co-chair, Decarbonize Newfoundland and Labrador

His own surveys show there is an appetite for wind, for example, in the far-flung Inuit communities of Labrador, which are predominantly diesel-powered and, as a result, have carbon footprints four to five times higher than your average provincial resident.

Without subsidies, they’d be paying about $1 per kilowatt-hour. Of the 211 people Mercer interviewed, only 10 expressed any level of opposition to wind energy. The rest responded favourably, in ways both humorous and sage.

“Ah b’y,” said one, “if we have to put up with the wind, we might as well get something out of it.”

Another — a community minister — said: “Inuit may not have a great deal of experience with wind power, but we certainly have a profound appreciation for the power of the wind.”

Funding St. John's climate plan

This energy environment is only one factor of many blocking carbon-reduction efforts in some provincial jurisdictions. In St. John’s, the province’s capital city, sustainability co-ordinator Edmundo Fausto said renewable energy expertise itself is hard to come by.

Even if the city could access funding necessary for large-scale solar, he said, it would struggle to find enough contractors experienced with the technology to do the installing. He also points out that Newfoundland and Labrador has among the highest rates of energy poverty in the country, so any and all climate initiatives must be planned carefully to avoid unsustainable spikes in electricity costs.

There are fewer provincial dollars available for climate change mitigation than Fausto would like. There is no money to formulate a climate mitigation plan for the municipality, an expensive undertaking and a prerequisite to accessing federal climate funds.

But Fausto does what he can with provincial money.

Bright spots include his proposed reforestation of 10 municipal acres and installation of two electric car charging stations. And Fausto is in the process of formalizing the municipality’s climate efforts.

This has included partnering with local organizations, associations, industries and community groups to cut carbon emissions where most practical. He expects to deliver a draft of St. John’s first municipal climate plan this summer.

City council also adopted a corporate climate plan in May that commits the City of St. John's to a 40 per cent cut in emissions from 2018 levels by 2030, with a stretch target of 50 per cent by 2030 and eye toward net-zero emissions by 2050 at the latest.

The province has other champions as well. Late last year, the Western Environment Centre (WEC), a registered Canadian charity promoting sustainability and carbon reduction, sent a letter to the premier’s recently appointed economic recovery task force, calling on it to transition away from fossil fuels and encouraging a hard look at the present and future of oil and gas exploration in the province. The task force's report, The Big Reset, was released in May and includes a road map for continued "low-carbon" oil and gas development — a move the WEC says amounts to greenwashing.

Still, regardless of the province's stance on fossil fuels, WEC executive director Katie Temple can see swelling public support for a renewable transition, even if the province’s leadership generally can’t.

“There’s a change in the air, and I think it’s a matter of politicians really realizing that people are ready to make a change,” she said. “I think there was this concern in politics that people are very emotionally tied to oil and gas, but the fact is, people are actually emotionally tied to their communities. They’re emotionally connected to their homes. Oil and gas can come and go, but we really need a good, strong economic plan that helps people stay in their communities and which is environmentally responsible.”

Comments