Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A coalition of coastal First Nations has achieved a significant step towards protecting the wild shores and waters of the Great Bear Rainforest on B.C’s central coast.

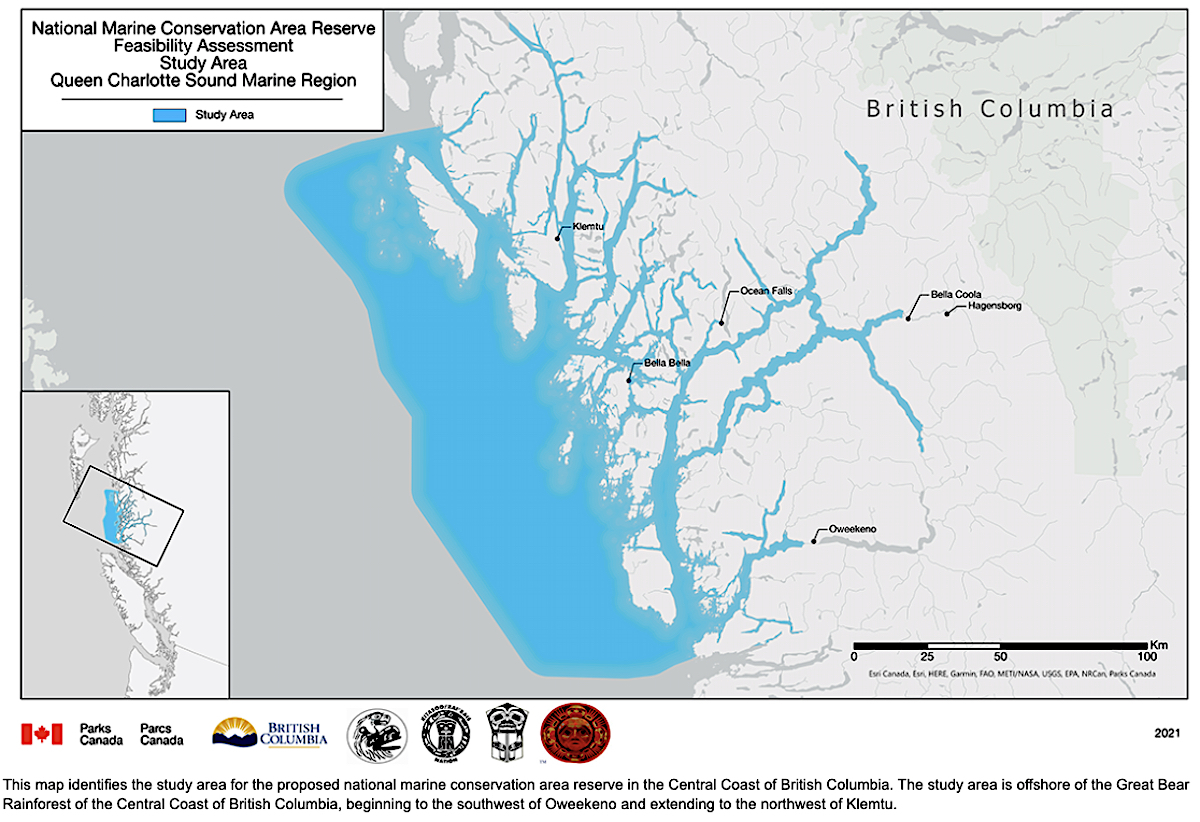

The Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Nuxalk and Wuikinuxv nations signed an agreement with Ottawa and the province of B.C. to do a feasibility study for a national marine conservation area reserve encompassing a significant section of the coast and offshore marine waters alongside the Great Bear Rainforest (GBR).

Heiltsuk Chief Marilyn Slett said the nation looked forward to collaborating on the study and developing a conservation approach and process that reflected its core values, practices, teachings, and principles.

“Our Gvi’ilas, the laws of our ancestors, (act) as the paramount principle to guide all resource use and environmental management,” Slett said in a statement Friday.

“Inherent in this is the understanding that all things are connected and that unity is important to maintain.”

A significant number of important cultural and spiritual sites, such as petroglyphs, burial boxes, and village sites — some which date back 14,000 years — are in the proposed conservation study area.

One of the largest tracts of temperate rainforest in the world, the Great Bear Rainforest is the size of Ireland and covers 6.4 million hectares, stretching the B.C. coast from the Discovery Islands in the south to the border of Alaska in the north.

A biodiversity haven, the region shelters the renowned Kermode “spirit” bear, famous for its white coat — as well as salmon, wolves, cougars, and grizzly bears. A total of 26 First Nations have territory in the GBR’s boundaries.

The proposed marine conservation reserve area in the Queen Charlotte Sound region would be wed to the shores of the Great Bear Rainforest. The proposed marine area is 14,200 square kilometres in size and features a coastline of steep-walled fjords and narrow channels, island archipelagos, estuaries, sandy beaches, shell-midden beaches, rocky shorelines, and open ocean.

The coastal region is a treasure, said federal Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson.

“British Columbia’s central coast is teeming with life and history,” Wilkinson said, “from countless marine species to the rich cultures and histories of First Nation communities.”

The isolated waters of the “Great Bear Sea” nourish some of the largest kelp forests along the West Coast, and harbour protected humpback whales, orcas, sea lions, and porpoises, as well as providing habitat for a host of endangered species, such as the marbled murrelet, sea otters, eulachon, and abalone.

The important step forward, in tandem with Indigenous knowledge and local stakeholders, will help Ottawa meet its international commitment to conserving 25 per cent of marine and coastal areas by 2025, and 30 per cent by 2030, he said.

“On top of helping to conserve biodiversity and cultural marine heritage, protecting marine areas also plays a critical role in mitigating the impacts of climate change,” Wilkinson said.

The proposed marine conservation area would compound the conservation values of the Great Bear Rainforest and reflect the holistic approach of Indigenous people, who see marine and terrestrial environments as unified and intertwined, according to Parks Canada.

The coastal nations’ announcement around the next step toward establishing a marine conservation reserve area builds on decades of marine planning along the entire Northern Shelf of the B.C. coast, said Erin Gray, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law.

“It’s a hugely important area,” said Gray, who is involved with marine planning for the legal non-profit.

“It’s exciting to see this initiated by the Indigenous nations, and being co-led by them along with the federal and provincial governments.”

If established, the central coast marine conservation area will become an important component of an even larger marine protected area network being planned for a vast section of the West Coast, from the top of Vancouver Island to north of Haida Gwaii, Gray said.

Consultation around the broader marine network in the Northern Shelf Bioregion is slated to begin in the fall and the goal is to complete the plan by June 2022.

The project is the result of co-operation between the federal and provincial governments and 13 First Nations, as well as a variety of stakeholder agencies and groups.

“The central coast, which would be a part of that larger network, would be a really important piece of that network,” Gray said.

The central coast feasibility study will examine what areas within the marine conservation reserve boundaries would be subject to full protection, and what would be open to sustainable economic activity, like commercial fishing, she added.

“I believe bottom trawling is out of the question, but the rest is all to be determined by this process.”

The study and potential conservation area on the central coast are based on a new model of collaborative governance and management with area First Nations that would depend on traditional and scientific knowledge to protect biodiversity, manage sustainable fisheries, and preserve culture, traditions, and economies of the nations that have long been stewards of the surrounding lands and waters, Parks Canada said.

The results of the feasibility assessment will inform future decisions about whether the proposal will continue, including boundaries and zoning, the federal agency added.

The protection and sustainability of the waters of their traditional territory is a priority for the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation, said Chief Doug Neasloss.

“We look forward to collaborating with Canada and British Columbia on the feasibility assessment for a national marine conservation area reserve, and learning how best to protect the marine environment and the ecological, social, cultural, and economic values that it sustains.”

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments