Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Two reports released Wednesday reveal Canada is lagging far behind its climate goals, with both studies making clear the only option left is reducing the production of fossil fuels.

The first is the United Nations Production Gap Report, launched in 2019, that compares governments’ planned fossil fuel production with the amount of production possible to hold global warming to the Paris Agreement target of as close to 1.5 C as possible. The study calls the gulf between planned production and what is compatible with 1.5 C warming the “production gap.”

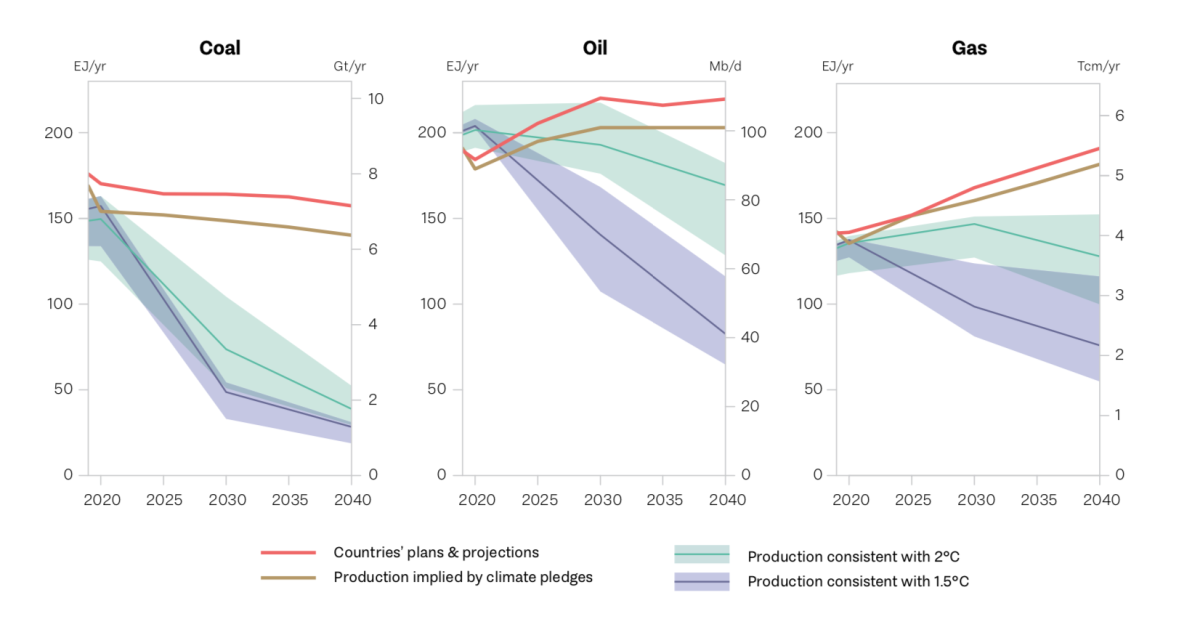

It found global coal, oil, and gas production should fall 11 per cent, four per cent, and three per cent annually from 2020 to 2030 to limit warming to 1.5 C, but instead, governments are collectively planning to increase production in oil and gas, with only “modest” reductions in coal. By 2030, the report projects 240 per cent more coal, 57 per cent more oil, and 71 per cent more gas than is compatible with 1.5 C warming.

That’s 5.3 billion tonnes more coal (or about 75 per cent of current global coal production), 40 million more barrels of oil per day (about half of current global oil production), and two trillion more cubic metres of natural gas (roughly half of current global gas production) over budget to keep global warming to 1.5 C, the report says.

The report ranks Canada fourth, fifth, and 11th for global gas, oil, and coal production respectively, where it was responsible for four per cent, five per cent, and one per cent of production. It also found Canada has 0.4 coal miners for every 1,000 workers, and that one per cent of Ottawa’s revenue comes from oil and gas production.

Canada is planning to increase oil and gas production, 18 per cent and 17 per cent respectively, from 2019 to 2040 under the Canada Energy Regulator’s latest scenario, the report finds.

The production gap report outlines Canada’s announced climate targets of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 40 to 45 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, and net-zero by 2050, but also notes that Ottawa sees the fossil fuel industry as critical for economic growth.

Just last week, the International Energy Agency released a global energy forecast that, for the first time, projected oil demand to fall in every scenario it considered, casting fresh doubt on Ottawa’s stated strategy of using fossil fuels to finance a green transition.

The second study is a report out of the Trottier Energy Institute (IET) at Polytechnique Montreal, which examined three sets of forecasts to study Canada’s progress towards its 2030 emission reduction goal. Those three forecasts come from the Canada Energy Regulator, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and the Canadian Energy Outlook prepared by IET.

IET executive director Louis Beaumier says the competing forecasts should push the federal government to be more transparent, because without all the data government modelling is based on, it is impossible to verify whether the forecasts hold up to scrutiny. Still, all emission forecasts point to the elephant in the room, which is oil and gas production.

Beaumier said that unlike the transportation or building sectors that will require replacing many vehicles and making many buildings energy efficient, the fossil fuel industry’s emissions come from far fewer places; namely oilsands businesses, refineries, power plants, and related infrastructure.

Reducing oil and gas production “is the most cost-effective way of reducing our emissions,” he said.

“If you reduce production, then you reduce all emissions related to that production.”

The report takes it a step further, calling oil and gas production “the only possible lever” to act on if the country is going to meet its critical 2030 milestone.

“Especially in the early stages of net-zero pathways, most GHG reductions must come from the industrial sector, including oil and gas production, electricity generation, commercial buildings, and transport-related activities, rather than from sectors like residential buildings and personal transport,” the report reads.

That’s because with less than 10 years to bend emissions 40 to 45 per cent from 2005 levels, there just isn’t enough time left to decarbonize the hard-to-abate sectors. For example, to push emissions related to heating residential homes down, there would have to be a massive scale-up of renewable energy and power grid capacity to keep people warm through winter. The study finds that short of a “significant acceleration in planning and investments,” the type of deep transformation that is needed is unlikely to occur in a 10-year window.

The study also notes an important shift in the federal government’s climate plans. By making a net-zero by 2050 target law, Ottawa has driven a nail into the coffin of all fossil fuel infrastructure.

“As long as 2050 involved an ambitious 70 per cent or even 80 per cent GHG reduction, it was possible to see partial decarbonization solutions, such as fuel switching or more aggressive energy efficiency measures, as viable,” the report reads.

“With a net-zero focus on a 30-year horizon, such an approach is no longer economically realistic. It makes no sense to deploy technological solutions, such as natural gas in transportation, that will have to be replaced in 15 or 20 years.”

Further, because all sectors have to be pushed to zero emissions, failure in one area cannot be compensated by another, short of carbon capture technology, which the study warns should “remain the ultimate backstop” given uncertainties about its ultimate efficacy.

John Woodside / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada's National Observer

Comments

We've dragged our feet far too long and now we have to act rapidly or miss the target. Where are the politicians with the guts to make rapid action happen? I fear Greta is right about hearing lot's of 'blah, blah, blah' and seeing little action.

The problem with the oil and gas industry is that although it's not really that huge a part of the economy as such, it's very, very profitable. That means that, in proportion to their size, oil and gas companies have a whole lot of slush for lobbying and PR and political contributions (ie buying politicians).

It's nice that the authors feel so responsible for green house gas emissions. Realistically 'though, we are, like with many other global problems, bit players: " ... it [Canada] was[is] responsible for four per cent, five per cent, and one per cent of production ...."

Given the scale of reduction required on a global basis, Canada could shut down its carbon-energy industry completely and make very little difference to the world-wide CO2 production; yet the impact in Alberta, Saskatchewan and BC would be catastrophic, with equally bad knock-on effects going East as far as PEI via compensation, tax losses, equalization payments, etc. NF&L would be in worse shape than Ethiopia.

I would find it much easier to get behind green, climate change initiatives if the proponents were urging transition plans that were considered and practical - not just shrill cries to 'shut down the oil industry - NOW'.

After the 10,000,000,000,000,000th time, one grows weary of the "Little Canada" fallacy.

At 1.6% of global emissions (just 0.5% of its population), Canada ranks 10th in overall emissions. (We rank nowhere near tenth in population.)

Using Canada's nominal (under-reported) estimates, 147 countries emit less GHGs than AB's oilsands industry. 169 countries emit less GHGs than AB. 183 countries emit less GHGs than Canada.

Canadians' carbon footprint is 3x the global average.

If Canada is "too small to matter," what message does that send to the 183 nations with smaller carbon footprints than ours?

*

Climate change cannot be stopped if only the biggest nations or top emitters reduce emissions. Even if the top 3 emitters reduced emissions to zero, that would still leave about half of global emissions on the table. Unless smaller national emitters do their part as well, global targets remain out of reach.

"All nations contributing less than 2% of emissions are, cumulatively, more important than India or China. It absolutely does matter that these nations reduce their emissions."

*

Canada has a small population of top-ranking emitters. High emitters are the problem. If other nations followed our example, global emissions would skyrocket.

*

There are billions of point sources of carbon in the world. All of them small.

If every state, province, city, town, family, or individual followed Mr. Ball's logic, no one would reduce emissions. They could all point to bigger sources elsewhere.

Why should anybody take any action on climate change? Nothing any one person, company, town, province, state, industrial project, etc., can do will speed up or slow down warming. But together they add up to one great big problem.

No one proposes that Canada act alone on climate change. Rather, all nations must act together. That is the only way to effectively address the problem.

Collective problems require collective solutions.

*

The fossil fuel industry has seen the writing on the wall for decades. Decades to prepare for the transition. Unfortunately, the fossil fuel industry has done everything in its power to obstruct the transition — and perpetuate demand: attack climate solutions, fund climate denial using Big Tobacco's playbook, oppose alternatives, campaign against carbon pricing, lobby to weaken and delay regulations, attack ENGOs, co-opt Big Green groups, and support politicians and parties who oppose change. All the while milking govts for endless subsidies.

Hopelessly disingenuous.

*

Either we manage the decline of the oilsands industry ourselves or let global markets do it for us. The latter route will be infinitely more painful.