Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

About 800 members of civil society groups berated countries on the last scheduled day of UN climate talks in Glasgow for failing to agree on strong action to avert the climate crisis while excluding people who are most affected.

Speaking at a "people's plenary" meeting Friday, youth, farmers, trade unionists, environmental groups, and disability and gender rights advocates criticized the event for being among the most exclusive climate negotiations so far. Following the event, activists flooded the COP26 venue corridors in a protest march out of the protected "Blue Zone" where world leaders gather.

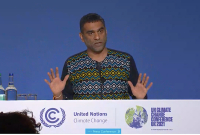

"The U.K. presidency has swept under the carpet all the opportunities for the people who are unable to speak to the global agenda in a way that can shape the course we are on at the moment," said Mohamed Adow, an international climate policy expert and founder of Power Shift Africa. "

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is built on the principle that countries' decisions and negotiations can be publicly scrutinized. With negotiations typically open only to observer groups — but not media — civil society groups play a critical role in making the process transparent to the outside world.

Observers limited

Organizers of COP26 in Glasgow had billed this conference as the most inclusive yet, despite criticism that delegates from poor countries were facing travel restrictions and struggling to get COVID-19 vaccines. However, even for the thousands who made their way to Glasgow this year, many negotiations were closed to observers because of COVID-19 capacity limits or security concerns.

The presence of observers has always been a touchy issue at COPs — short for conference of parties to the UN agreement —explained University of Ottawa professor and climate policy expert Ryan Katz-Rosene. While they can provide more transparency and accountability, their presence also means they can give near real-time feedback to negotiators. That's particularly concerning when industry lobbyists are also talking to negotiators. The presence of civil society groups and journalists can provide an important counterweight, he said.

At a press conference Friday, Friends of the Earth Scotland climate and energy campaigner Catherine Rance pointed out fossil fuel lobbyists were welcomed into the negotiations, and the U.K. had not yet respected its pledge to end fossil fuel subsidies overseas. An informal analysis by the research and independent non-profit constituency group at COP26 found that there was a 77 per cent increase in the number of delegates attending the event, including 232 per cent more media organizations and 74 per cent more non-profits than at COP25.

Yet capacity limits in the negotiations rooms mean that boost in attendee numbers had little impact on how many people were actually in negotiating rooms or even admitted to press conferences.

The restrictions have exacerbated frustrations with the overall pace of negotiations critics say haven't been ambitious enough to reflect the severity of the crisis.

"Governments in the UNFCCC have repeatedly failed to deliver meaningful and just outcomes that will keep the global temperature rise below 1.5 C," said Adow. "Despite growing urgency, time is running out. Countries from the global North have the greatest historical responsibility for emissions and have grown rich from colonization and the exploitation of communities in the global South."

A draft text released Friday morning called for countries to double funds available to help poorer nations adapt and called on countries to provide stronger emission reduction targets by next year. Yet the text remains contentious as countries dispute money, the speed of emissions cuts, and whether "fossil fuels" should be included in the text at all.

Twenty-three developed nations including Canada, the U.S., and the U.K., are responsible for half of historical CO2 emissions, according to the Global Carbon Project. Annually on a per-capita basis, Canada, New Zealand, and the U.S. ranked at the top of the list this year.

No plans to cut oil production

Environmental groups have repeatedly called on major fossil fuel producing countries to cut back production. A September study in the journal Nature found that about 90 per cent of the world's remaining oil and gas reserves must remain in the ground to have even a 50-50 chance of keeping global warming below 1.5 C.

Despite being the world's fourth-largest oil and gas producer last year, Canada has no explicit plans to cut back production. In a Friday interview in Glasgow, Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault said the federal government doesn't have jurisdiction to curb production. Instead, the country last week announced a new plan to cap the nation's emissions.

"People say you need to keep (fossil fuels) in the ground," he said. "Ultimately what counts is what the atmosphere sees. If the atmosphere sees less emissions, we're achieving our goal."

Still, speakers at the people's plenary were clear that countries' pledges — including Canada's — continue to fall short. Current policies and actions are expected to send global temperatures soaring between 2.5 C and 2.9 C, according to the Carbon Action Tracker.

Environmental, Indigenous and human rights groups are also concerned that net-zero plans that try to neutralize emissions by sequestering CO2 in natural environments like forests will further push Indigenous people and peasants off their land.

Those concerns were echoed earlier in the day by Eriel Tchekwie Deranger, executive director of Indigenous Climate Action. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement — a contentious provision that would create international carbon markets — would put many Indigenous people's lands, territories and rights "further at risk," she said.

What's needed is a wholesale transformation of our economies and philosophies, said speaker Ta'Kaiya Blaney, an Indigenous youth climate activist from the Tla'amin Nation on B.C.'s west coast.

In this respect, the climate conference has failed, she said.

"COP26 is a performance," she said. "It's an illusion constructed to salvage capitalist economies rooted in resource extraction and colonialism ... It is what caused climate change, and I'm not going to my colonizer for solutions" she said.

Comments

I checked to see if Thunberg had stuck by her principles, and not flown. Indeed, she got back across the Atlantic on another hobbyist sailboat, and has stayed there since. And of course, most of western Europe can be traveled on electric trains. (Even diesel-run trains are the last-carbon-emitting thing we've got, per passenger-kilometre.)

But everybody else, while lionizing her, has not emulated the discipline. I sigh to see how many Canadians have gone there, basically to get their message in the media, by flying. There are so many of Canadians and Americans that they could have chipped in and hired a sailboat, if they wanted to be theatrical; or just thought way ahead and rented the few rooms available on cargo ships that are going to Britain anyway.

But, nooo, they are all sending a message of "THIS IS A CLIMATE EMERGENCY....except when I need to pursue my own messaging interests, which are well-worth a 1.25 tonnes of carbon emitted per passenger, for a transatlantic round-trip flight."

If these people want to be "leaders", they need to understand that you lead by example. That's why an autistic teenager was lifted up to fame she never asked for.

Oh, right, forgot to mention: what's the National Observer's excuse for emitting a couple of tonnes of carbon (since the journalists sent probably came from BC, so more like 2 tonnes emitted, round -trip) to have their own journalist go?

Couldn't you have shopped around Britain for a compatible, professional journalist, hired that person to cover COP26, and spared the atmosphere the carbon? How many people did the NO send?

I'm going to remind the NO of that every single time they use the term "climate emergency" until the next COP.