Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

After a devastating wildfire season that reduced towns to ash and a heat dome that killed hundreds, climate breakdown is again threatening British Columbians, as torrential rain pummelled the province Monday, causing landslides and floods that destroyed key infrastructure and took at least one life.

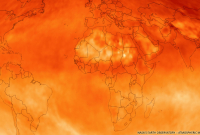

The extreme weather was caused by an “atmospheric river” that carried water vapour from the tropics to B.C. The heavy downpour mixed with melting snow, leading to flooding. While the full extent of what factors allowed the emergency to unfold is not yet known, it is expected wildfires that burned healthy forests contributed by reducing vegetation that could absorb moisture.

“You can see in the Okanagan the effects of the fire would create very permeable areas, and then there are other places where the ash has fallen,” said Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) meteorologist Mindy Brugman.

Ash settling on the forest floor can impact the watershed by affecting how much moisture can evaporate. Wildfires also, of course, burn trees, meaning the roots are not absorbing moisture the way they previously did.

Wildfires “kind of change the hydrology of the whole network,” Brugman said.

Those tree roots also help reinforce the soil, and when damaged, landslides become more common. Landslides can dam rivers and exacerbate flooding. In other words, what B.C. is experiencing is a lethal mix of cascading climate impacts.

“We're on the edge of a big increase in these [storms],” said Brugman. “Some areas will get incredible amounts, particularly the Arctic and our West Coast, but even more so if you look at the East Coast like Halifax and even Ottawa,” she said.

Brugman described modelling from ECCC based on 3 C warming that predicts an increase in the frequency and severity of storms, particularly in the Arctic where the loss of sea ice is expected to lead to unprecedented Category 5 storms by 2080 that could last for more than a week.

“The same general rise in atmospheric temperature that allows for extreme heat in the summer also creates the capacity for the air to hold more water vapour that leads to these kinds of destructive atmospheric rivers and heavy rain events,” said climate advocacy group 350’s Cam Fenton.

“Literally the same places have been impacted … by these two ends of the climate emergency,” he said. “This summer the highway was closed, flames were jumping across the highway, and then [Monday], the rising water actually washed away and shut down that highway again.”

The Canadian Forces told Canada’s National Observer that 311 people were rescued from vehicles on the highway Monday after being stranded by landslides. That rescue mission is over while the RCMP takes up the search for people who still need help. As of Tuesday afternoon, the Forces confirmed B.C. has not requested further assistance.

Thousands of people were evacuated from Merritt and Princeton on Monday as the communities were submerged. Those communities are in Conservative environment critic Dan Albas’s federal riding, who said the extensive damage was made worse by inadequate water and sewage infrastructure.

“What we're seeing here is that the extremity of the situation was worsened because of the forest fire situation, and has led to much of the damage that we've seen here,” Albas said.

Albas said the first priority is making sure everyone is safe and supporting those displaced, but the province should undergo a review of its emergency preparedness. Further, Albas says the province needs to lead in an emergency like this.

“One of the challenges is that you have a series of localized crises that are being managed by municipalities; but the province does need to take the lead, in my perspective,” he said.

“The province is the one that has many emergency powers … it can request further assistance from the federal government. [Emergency Preparedness] Minister [Bill] Blair made it very clear to me that he's offered every support, and the province just needs to ask.

“So the province needs to do an assessment of what's required and take that leadership role we know we need,” he said.

Albas also said that with key infrastructure damaged, issues around supply chains will be ongoing.

At a press conference Tuesday, B.C.’s Public Safety Minister Mike Farnworth said after any extreme weather event, the province will undertake a review. When asked if the province should have taken further steps to warn people about the emergency, Farnworth said alerting took place locally, and there was plenty of warning “out on the media.”

“What we saw was an absolutely unprecedented deluge like we’ve never seen before,” he said.

“Obviously after any event such as this, the province assesses what [happened] and lessons [are] learned for the future.”

NDP emergency preparedness critic Richard Cannings said the federal government should put more money into its disaster mitigation and adaptation fund. That fund was launched in 2018 with an investment of $2 billion over 10 years. Budget 2021 added $1.375 billion over 12 years, with about 10 per cent of that extra amount earmarked for Indigenous recipients.

Cannings said there isn’t enough money on the table to help communities devastated by extreme weather, let alone enough to help communities prepare.

“If you're saying, 'I want $20 million to [prepare] our community so it doesn't get flooded,' you're at the bottom of the pile when there's a line ahead of you of communities that are trying to rebuild, [and] they're obviously a higher priority,” he said.

“So I think we have to really look at climate adaptation seriously and give it the attention — and most importantly, the funding — that it needs.

“Let's not wait for towns to be destroyed before we give them money,” he said.

John Woodside / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada's National Observer

Comments

It is fashionable to weave forestry into climate-change these days. But fashion is one thing and the forest/climate dynamic quite another. Confusing the two leads to trite journalism.

In this article (but it could be in almost any article on climate change and/ or old-growth forest policy), the notion that tree roots hold soil together and that dead trees (killed by wildfire) do not absorb water and so, therefore, landslide risk increases with heavier rainfall are two examples of the kind of confusion, conflation and fashionability we see more and more of as citizens cast about for a confirmation narrative of what they believe should be done—meaning, in this and many other instances, to stop logging.

Yes, slopes freshly denuded by wildfires in the Interior are at higher risk of failure when loaded with excessive rainwater, as they would be if they had originally been covered with trees or grass. But, as we seen on the news in Coastal areas where high rainfall is normal (and super-high is not), the landslides contain debris torrents composed of old-growth trees. If it were true that their roots prevent failures by holding soil together, then there would not have been the slides we’ve seen in the past few days. Many if not most of these slides have never been logged on the Coast specifically because of the landslide risk—the matter here being not logging policy (moot in most cases, as mentioned) but, rather, excessive rainfall. Some crusading OG preservationists would blame that excessive rainfall on BC logging policy (or maybe even Coastal logging policy) but, naturally, they are confusing local weather with climate and, in the process, getting waylaid in the mugs’ game of equating CO2 sequestration, OG logging, and remedial polices.

Further, the statement here that the roots of trees killed by wildfire don’t hold water is back-hander hackneyed. First, there are few Coastal stands destroyed by wildfire anyway (the few places there have been recent Coastal wildfires are tiny compared to the huge conflagrations in the Interior; the factor is somewhat offset by steepness-times-high rainfall on the Coast), but, second, tree roots—wherever they are— do not absorb groundwater in the late fall to early spring when heavy rains fall—they are dormant and not using water; rather they absorb a lot of it in late spring when it rains a lot, and absorb steadily decreasing amounts of it for growth and cooling until summer dormancy when absorption almost stops.

The closest thing I can think of that involves trees, logging and soil stability is the theory that large stumps left after logging OG on steep, susceptible slopes begin to decay, leaving vacuoles once occupied by roots in the soil where groundwater can thence accumulate and bear extra weight onto the slope. But slope stability is very, very complex, and, in any case, logging is not permitted where requisite geo-technical surveys have determined a significant risk of failure. That leaves the large swaths of burned-over forest regions of the Interior to assess and allocate resources to ameliorate extreme weather events we now have to admit are heading our way. BC’s Interior forests are, by nature, relatively difficult to regenerate. Rather than attempting to establish forest root systems in order to prevent slides, it’s likely converting these areas back to grassland (like they were before we started suppressing wildfires a century ago) would be more salutary given that hotter, drier summers are coming at us. Too bad because living forests do decrease slide risk, mostly by cover which prevents soil surface erosion, but also by root structure—not water absorption capacity— underground. More important than water absorption is evaporation from tree foliage: a substantial proportion of rain on a given area of forest cover is intercepted by trees before it makes it to the ground and evaporated—it can be, in warm and/or windy days, up to half of the total rainfall.

There is no doubt that human-caused climate-change (the most substantial kind these last few centuries) is affecting forests and local weather events. However, the journalistic risk is over-generalization, confusion of global climate dynamic with local weather and, especially (IMHO), blithe blaming of whatever political party happens to be governing for not immediately slamming on the brakes, a convenient and reactionary scapegoating that is as potentially inciting as it is fanciful.

It remains that two centuries of industrial, civic, and agricultural activity have banked a huge amount of consequence which will take incremental, multi-pronged approaches to ameliorate over at least as long as it took to get here. Politics is never easy and it sure ain’t with this file. Nevertheless, people are all too quick to panic and blame government when only government can manage such a huge task. As we’ve seen with Covid, citizens are ready to ‘drop the gloves’ and fight to get back the conveniences they’re used to, and are all too quick at expecting one approach, vaccines, to take care of it all. An overdose of pseudoscience develops to effectively throw gas on this, the wrong kind of fire. Similarly, West Coast old-growth should be preserved for its own sake, especially when some types are nearly extirpated; but expecting climate change to be solved by immediate cessation of OG logging is a fantasy, and perversely arguing that regenerating new forests is ineffective (so-called “net CO2 emission”—which is more accurately about OG itself) in order to make that wonky preservation case actually diminishes one of the easiest ways—short of reducing CO2 emissions—to capture CO2. Again: over-generalized and simplistic, yes, but also counter-productive in political terms.

We’re at the beginning of climate consequences and obviously need to —once we get over the usual shock—prioritize areas at most risk for immediate remediation while maintaining At the same time a steady course of many small, interwoven and public ally co-ordinated measures to reduce atmospheric CO2.