Canadian researcher on why you should care about the Thwaites Glacier

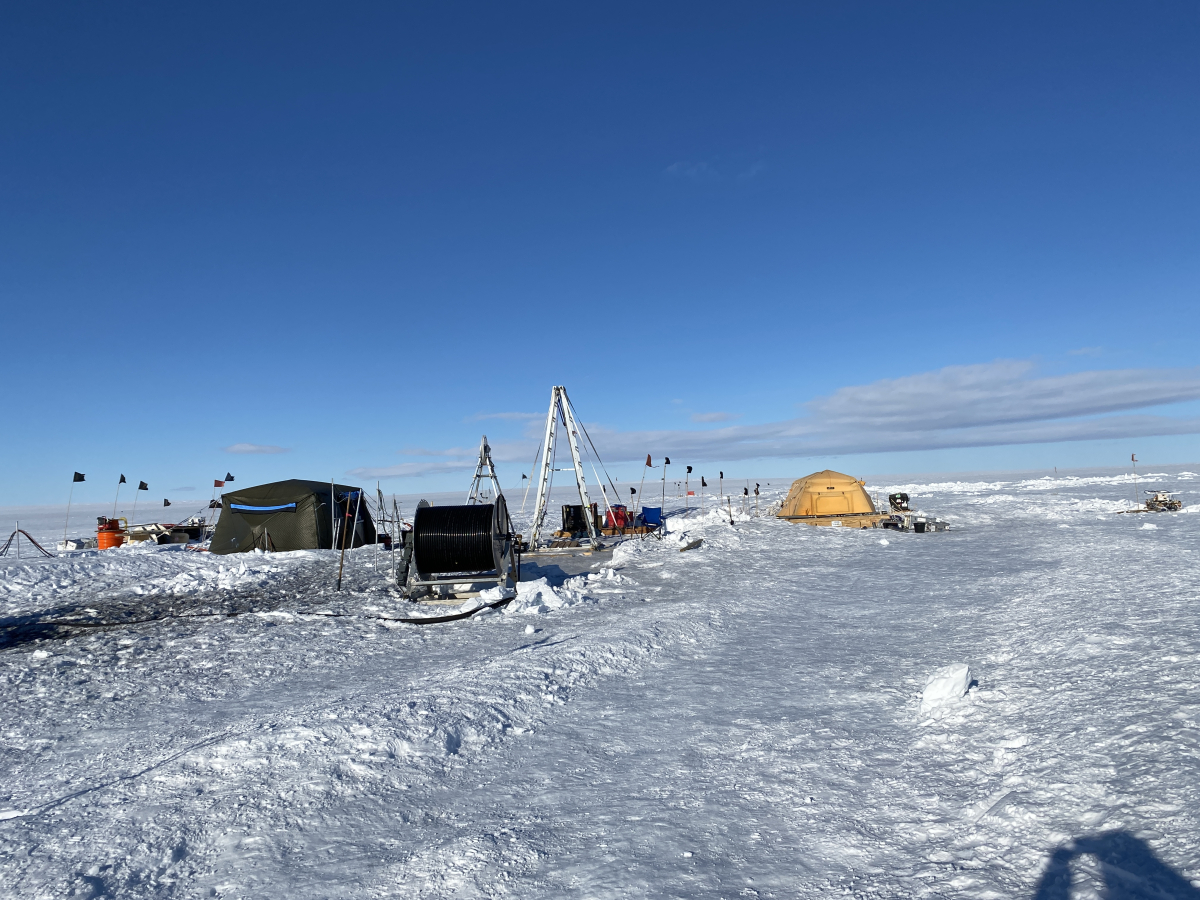

Over the weekend, physical climate scientist David Holland made it to his research base on the Thwaites Glacier — a vast, unstable and vital ice formation in Southern Antarctica that researchers have scrambled to understand.

There he will study the troubling changes in the eponymous Thwaites Ice Shelf, which acts as a dam for the rest of the ice mass, said Holland, who lives in Newfoundland but works as a professor of mathematics and atmosphere and ocean science at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University.

Significant cracks in the shelf began to appear in December, signs some scientists believe indicate it could fall away within the next decade. Its demise would spell the beginning of the end for the glacier and cause significant sea-level rise. The mass is already a contributor to rising waters — according to NASA, melting at Thwaites currently contributes four per cent of annual global sea-level rise.

Holland has spent the past decade doing research at Thwaites. This year, he will remain at the base camp for about a month, measuring sea ice and water temperatures. He’ll use the data to simulate how changes in Thwaites’ size could affect sea-level rise, and how warming ocean temperatures accelerate that shift. Speaking on a crackling satellite phone from the RV Araon, the South Korean icebreaker ferrying the team to its destination, Holland compared the calculations to a weather report.

For weather reports, forecasters use a computer model to solve a math equation, called the weather equation. “They can tell you what the weather will be tomorrow. That’s what you see on your iPhone. And that took 70 years to develop and an unbelievable amount of research,” he said.

“We're trying to forecast what that glacier will do not next week, but next decade. Next century. Glaciers move a bit slower.”

Holland was watching sea ice float by as he spoke to Canada’s National Observer from his cabin. The undertaking is made possible through the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, he explained as well as the Center for Sea Level Change at New York University Abu Dhabi, which Holland directs. Canadian helicopters are shuttling gear from the boat to the research site.

When Holland started travelling to Antarctica in the mid-2000s, he spent most of his time at the Pine Island Glacier — a huge ice stream that has melted significantly in the past few years, losing one-fifth of its area from 2017 to 2020.

Although the Pine Island Glacier is an important piece in understanding the state of sea ice in Antarctica, the Thwaites Glacier was largely ignored until about 10 years ago, explained Holland, who said deciding where to study was like “fumbling through scientific darkness.”

Even now, a decade into analyzing Thwaites, mystery still abounds.

Holland raises “hmms” at recent headlines about the glacier. Words like “doomsday” have populated news stories, which detail the discovery of new cracks throughout Thwaites and how those fissures could signal a significant change in the glacier over the next five to 10 years. If the floating section in question was to break off, it would trigger a sea-level rise of several feet. Holland said it could happen, but other outcomes are also possible.

He stresses the importance of understanding the Thwaites’ projection, but also underscores how little we know. He describes Antarctica as mysterious — much like space or the deep sea — and says it’s difficult to predict how quickly the glacier will break off.

“The idea that people want a quick answer is not on the table, it's not going to happen … Thwaites is the most vulnerable place on Earth for a big glacier to collapse,” he said.

“Will it happen now? It's possible. It happened in the past. But we don't have glacier forecasts. Right now, that could be a problem.”

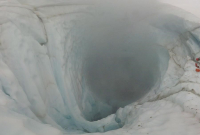

Warm water is affecting Thwaites, explained Holland, who is set to drill a relatively small (but effective) hole into the glacier to measure water temperatures far below. The warmer water circulates from the Amundsen Sea, which melts ice and loosens Thwaites from the bedrock it straddles. A 2019 study published in Nature Geoscience said the trajectory at the glacier is directly attributable to climate change.

Warm water was detected at Thwaites in February 2020, where for the first time, temperatures were recorded at more than 2 C above freezing.

The faster Thwaites melts, the higher the oceans will rise, impacting coastal cities worldwide. Holland stresses how all oceans are connected, and that coastal cities in Canada such as Victoria and Canada would see significant change if the Thwaites Ice Shelf were to fall.

In turn, Canada also affects what happens in Antarctica, especially since it's the only G7 country other than the U.S. where emissions have risen every year since the Paris Agreement.

“One of the details is that the weather in the North Atlantic is directly affecting the weather here at Thwaites. The way our planet is formed and the short story of it is that everything is connected to everything,” he said.

“Canada is very much connected.”

Holland said he thinks about that interconnectedness while on Thwaites — he said a peaceful feeling of just being couples with the amazement of how small, yet boundless, it feels to be in Antarctica.

At times, Holland’s journey may be treacherous — he and his fellow researchers were seasick for days, and on one occasion, his chair leg broke during a particularly rocky stretch of sea, sending him flying across the room.

Holland, who has been obsessed with the Antarctic and science since he was a child in Newfoundland, approaches Thwaites with a mixture of inquisitiveness and urgency. Understanding the trajectory of the area through glacial forecasting is essential, he said, and he hopes the next generation of scientists will be as keen as he is.

“People have no idea how difficult it is to get observations at the ends of the Earth, and the amount of commitment it's going to take,” he said, emphasizing there is plenty of funding for research at Thwaites.

“We have to capture the imagination and the hearts of young people … the opportunity to understand is amazing. The ball is coming in their hands very quickly.”

Comments

Those of us on the West Coast who experienced the recent record-breaking fresh water flooding in the Fraser Valley can only imagine the scenario in another generation or two with the rate of sea level rise boosted by the break up of the Thwaites Glacier. Salt water infiltration up through the ground in Richmond (pop. 225,000) is already here. The highest natural elevation in Richmond is one metre below sea level at today's average high tide. King tides, storm surges, dikes sinking under their own weight on the soft alluvial soils, erosion of river banks, hundreds of billions in public infrastructure and private assets (homes, businesses) under threat and more will be enormous considerations for all levels of government and all citizens.

Those who are tasked with planning for the future will no doubt be terribly frustrated by politicians who study and talk and wave their hands in the air on climate change, but never follow up with an actual plan of action with hard deadlines and adequate financing until the dikes collapse. Then it's policy by panic that comes too little and too late.

In this case, several Metro communities with over 300,000 people and the vast Port of Vancouver are at risk. Not to mention Victoria, Nanaimo, Campbell River, Prince Rupert, Halifax, Saint John, Fredricton, Saint Johns, Charlottetown and many coastal small towns. The adaptation planning must start now.

Personally, I don't have a lot of confidence in governments. Both Justin TMX Trudeau and John LNG Horgan have made infant steps that they crow about like they are Jolly Green Giant twins. Jason Kenney is at least honest about where he stands. The reality is that both the province and the nation have ramped up emissions; Canada is the only G7 nation to have not stabilized or lowered its carbon output. The proof of the willfulness of their ignorance is belied by their "shock" when an extreme climate event (or series of events) dominates the news, knocking even a worldwide pandemic off its Number One news cycle pedestal for an entire week at a time.

Unprecedented heat domes, floods, forest fires and polar vortexes do have a tendency to sneak up on you when you are trying to carry on building oil pipelines, allowing constitutional exceptions to basic safety standards at oil storage tank farms and ludicrously couching subsidies for oil industry carbon capture and storage as "good for the economy" while national smart grids, catalyzing better urbanism through transit / poly-zoning, and actually sitting down and writing a realistic National Climate and Adaptation Plan are thrown nickels and dimes, or filed away in some distant idea storage warehouse.

That leaves it up to citizens and cities to put 2 + 2 together, realize that this issue is now beyond acts of protest and civil disobedience and quietly undertake an actual planning process for their own survival. But they do not have the capability to put out to tender a retreat from the sea, or to float their cities and farms on gigantic ferro concrete rafts or other strategies that seem outlandish until there is actually a series of humongous and very deadly saltwater inundation events, starting say about mid-century, that wreck entire cities.

"Oh, we were caught off guard" followed by yet more repetitive apology just doesn't cut it today after 34 years (and climbing) of unassailable climate science and deadly extreme event evidence.