Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

New research exposes a “deep entanglement” between the fossil fuel industry and those who govern Canada’s biggest pension funds, raising concerns of potential conflicts of interest.

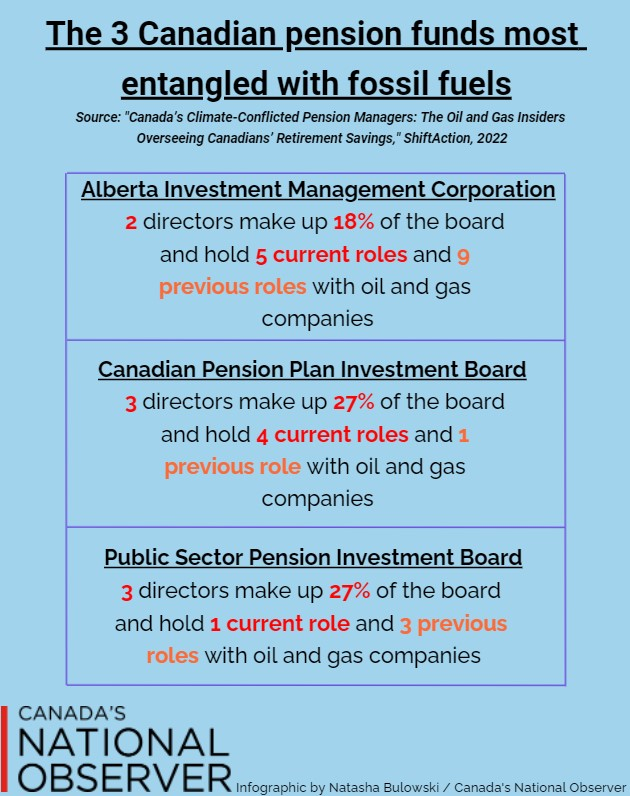

Seven of Canada’s 10 biggest pension funds have at least one board member who also sits on the board of a fossil fuel company, according to research done by ShiftAction, a charitable initiative that works to protect pensions and the climate. Across all 10 pension funds, 80 different directors, trustees, executives and senior staff held or currently hold roles with 76 different fossil fuel companies.

This was disturbing news for 65-year-old Ellen Campbell, a former Alberta government worker who wishes her life savings were not being invested in an industry that is one of the main drivers of climate change and one that regularly acts to block climate policy.

“I'm receiving a pension and I would far prefer that it has nothing whatsoever to do with the destruction of our planet. But at the same time, I don't know if I have very much control over where and how they invest money,” Campbell, who has been collecting her pension for a decade and now works as an English as a second language teacher, told Canada’s National Observer.

She said learning Canada’s largest pension funds share board members with climate-harming fossil fuel companies makes her even more worried about the futures of her children and grandchildren — will they have a livable planet and a good pension?

Canadians’ retirement savings are exposed to unnecessary risk when pension funds remain heavily invested in companies “on the wrong side of the energy transition,” said Adam Scott, co-author of the report and director of ShiftAction.

Canada’s six biggest pension funds have pledged to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) becoming the most recent fund to commit to net-zero. But Scott said these promises are lacklustre: as of March 2021, over $17 billion of CPP’s portfolio was invested in fossil fuels, ShiftAction noted in a press release.

Fossil fuel companies’ bottom lines rely on the continued use of their products — which are a primary cause of climate change, Scott said. ShiftAction does not see a “credible, profitable pathway” for the industry to survive in the energy transition, he added.

Pension funds must act quickly to change how they manage investments in the face of the climate crisis, he said. But they may be less likely to adopt policies to wind down finance for fossil fuels if doing so is seen as undermining “the interests of some of their directors,” he added.

“The best interests of pension beneficiaries are not at all the same as the best interests of the shareholders of a fossil fuel company,” said Scott. “And if you have directors who are legally beholden to both, you have a problem.”

Scott emphasized the report cannot determine whether conflicts of interest are actually occurring but believes “there’s a great potential” given the report’s findings.

“We know … most (pension fund) boards have protocols in place to deal with conflicts of interest… We just don't know if they're being applied in this case,” he said, citing a lack of disclosure and transparency.

“We need more information from the funds about how they're making sure that there is no conflict there.”

Within Parliament, Independent Sen. Rosa Galvez is pushing hard for better transparency from financial institutions. She tabled a new Climate-Aligned Finance Act earlier this year that seeks to address the problem and requires financial institutions to align with Canada’s international climate commitments. The bill, which had its second reading May 5, includes a pathway to ensure directors appointed by governments have climate expertise and are not affiliated with any organization that fails to line up with the country’s climate commitments.

Even if board members don’t have a conflict of interest, they might simply lack expertise on climate risk and not know how to act in the best interest of pension plan members, the report says.

Galvez’s bill has great potential to get pension funds — and the financial sector writ large — on the right track, according to the report.

The senator told Canada’s National Observer the ShiftAction report confirms her pre-existing concerns about conflicts of interest among higher-ups in financial institutions.

“I don't see how we're going to walk in the direction of the net-zero 2050 goal that we have set ourselves,” Galvez said. “It's impossible because people are in conflict situations, they have this fiduciary duty to return investment to the (pension) contributors, but then they have other fiduciary duties if they are also sitting on a fossil fuel board.”

This is akin to a doctor sitting on the boards of a tobacco company and a hospital, said Galvez, pointing to the World Health Organization’s refusal to accept Quebec’s Medicago COVID-19 vaccine because of the company’s ties to Big Tobacco “We wouldn’t accept that.”

Galvez said most workers, herself included, unknowingly contributed to climate change when they put their trust in financial institutions, pension boards and unions. If pension plans don’t divest from fossil fuels and learn to manage climate risk, young people will bear the consequences, she added.

As the world transitions to a low-carbon economy, large pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure will lose their value, and pension funds with a stake in these projects will end up suffering big economic losses, she explained. Young people contributing to these pension funds today and in the coming decades will feel those losses acutely in the latter half of the century.

For many, climate change has or will result in losses of homes, livelihoods and health as extreme weather events occur with greater severity and frequency, she said, and money invested by pension funds on behalf of workers will be partially to blame.

Natasha Bulowski / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments

Yes, two of the most pressing issues of our time, climate inaction and housing unaffordability -- and pension funds are implicated in both.