Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Lobbyists working the halls of Parliament on behalf of interest groups will soon have new rules around campaigning for politicians and stricter rules around gift giving.

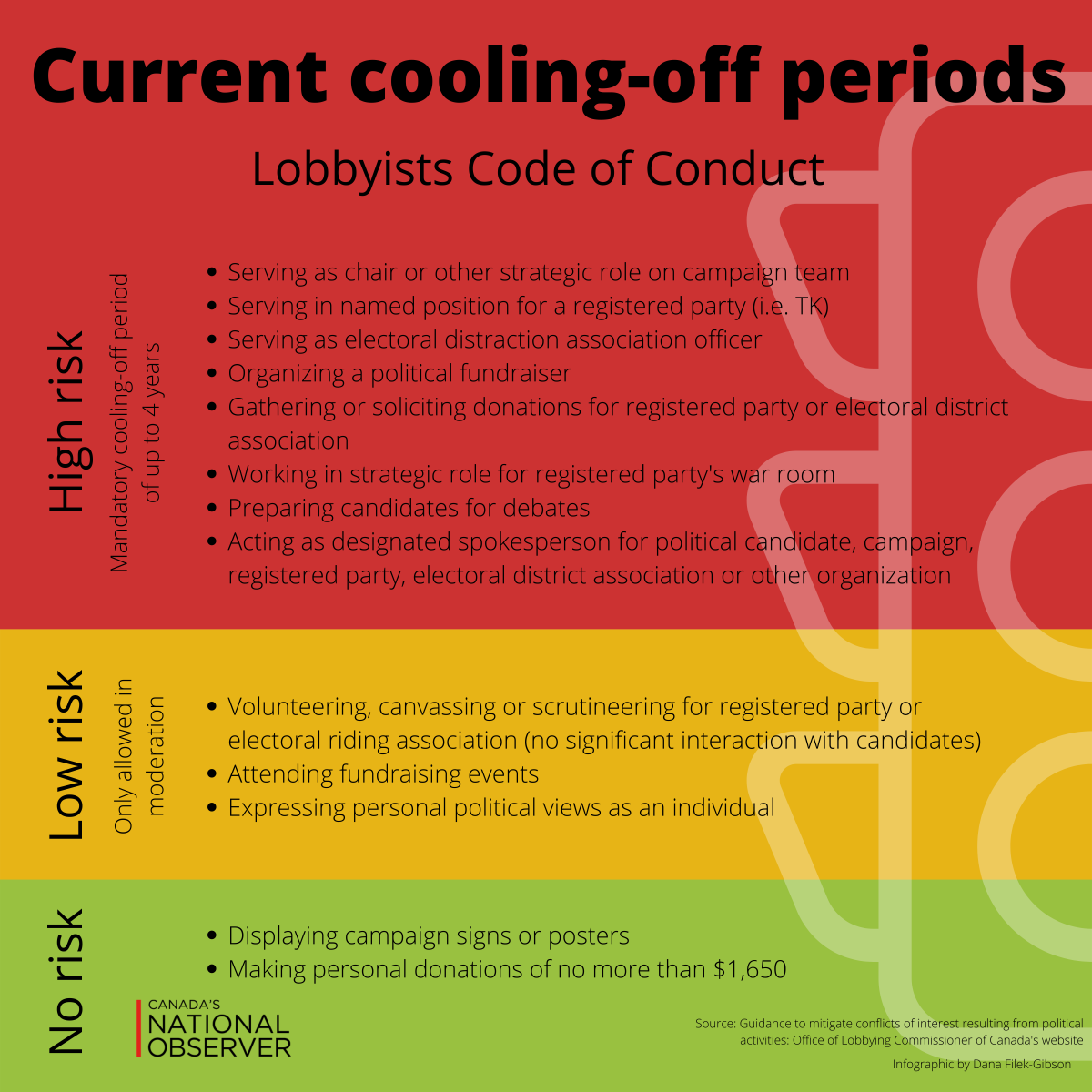

Lobbying commissioner Nancy Bélanger is proposing changes to the Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct to reduce its cooling-off period, which restricts lobbyists from contacting federal politicians they have worked for during election campaigns. Cooling-off periods are deemed necessary because a lobbyist’s involvement in a political campaign can create a sense of obligation if the person they assist is elected to office.

Instead of restricting contact for a full election cycle, which can be as long as four years, the new cooling-off period would be set at two years for lobbyists who conduct “significant” work on behalf of a candidate or official. That includes organizing a political fundraiser or working in an election war room, where political strategy is designed.

Lobbyists who contribute in more minor ways, such as drafting campaign materials, canvassing, gathering donations or distributing campaign materials, will have to wait one year. They are still allowed to display lawn signs, make political donations, attend an occasional fundraising event or do strictly administrative work like envelope stuffing from time to time.

Under the current rules, low-risk activities like volunteering, canvassing and attending fundraising events are allowed, but if they occur too frequently, the lobbyist risks straying into high-risk territory and the associated cooling-off period of one full election cycle. The lobbying commissioner’s office encourages lobbyists to contact the office “when their involvement in lower-risk political activities becomes frequent or includes multiple interactions with a public officer holder, so that they can appropriately assess when they need to respect the cooling-off period.”

Currently, the only activities 100 per cent risk-free for lobbyists are displaying lawn signs and making a personal donation of up to $1,650 as permitted by Elections Canada. The proposed changes would add several activities to that list, including attending a fundraiser or campaign event, expressing personal political views and doing purely administrative tasks.

Consultations on the proposed changes ended in mid-February and the submissions are now posted online. Bélanger said no final decisions have yet been made but noted her office received feedback that a full election cycle was too long. The commissioner settled on the proposed periods because “generally in law, cooling-off periods are usually two years,” she said.

Bélanger told Canada’s National Observer her intent is to clarify the rules for the benefit of both lobbyists and the department.

Depending on who you ask, proposed changes will either gut key rules of the code and open the door to more unethical lobbying tactics or unreasonably curtail the freedom of lobbyists to participate in politics.

Cooling-off period reduced

Duff Conacher, co-founder of Democracy Watch, says the new cooling-off periods are significantly weaker than the current ones.

The idea behind these rules is that a lobbyist shouldn’t be doing more than the average voter to help with election campaigns, or else they’ve crossed a line, said Conacher. But an average voter doesn’t work alongside candidates and is unlikely to go door-knocking on a frequent basis, if at all, he said.

“What [the commissioner] is proposing is that you can fundraise for a politician, work in their campaign office in some roles, canvass for them every day during the campaign and draft campaign materials, and then you'll be able to lobby them one year later,” said Conacher.

“It's just absolutely ridiculous to pretend the conflict of interests from helping them win through (those activities) just disappears in one year, let alone in two years.”

“They owe you at least until the next election” and often longer than that, he said.

In an email to Canada’s National Observer, Jason Kerr, president of the Government Relations Institute of Canada (GRIC) said the proposed one-year cooling-off period for minor activities will infringe on Canadians’ freedom to participate in electoral politics and violates sections 2 and 3 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, he said GRIC recognizes significant political work like managing a campaign might create a sense of obligation and “in these limited cases, a cooling-off period may be reasonable.”

Kerr’s concerns are reflected in a joint submission from GRIC and the Public Affairs Association of Canada (PAAC).

Suncor also submitted comments during the consultation period and acknowledged significant political work should require a cooling-off period as the draft code proposes. However, Suncor requested “other” political work, like canvassing or gathering donations, be excluded from the cooling-off period to allow lobbyists to “be involved in the democratic process of an election.”

Close relationships and gifts

The code also contains some broad rules designed to prevent conflicts of interest by directing lobbyists not to lobby public officials with whom they share a relationship — such as friends, family or financial or business partners — that could create a sense of obligation.

Bélanger’s draft changes would expand the current definition to include working relationships like sitting together on a board of directors or being colleagues and workplace allies.

Kerr says this definition of a close relationship is too broad and “simply working in the same office or sitting on the same board should not necessarily constitute a close relationship.”

Conacher, on the other hand, maintains that including colleagues in the definition of “close relationship” is important.

If a lobbyist can prove they don’t have a close relationship with an official they worked with, that’s fine, but proof is necessary because even the appearance of a conflict of interest can undermine the public’s trust in government, Conacher said.

The draft changes also include a $30 limit on gifts, such as food, beverages and travel, to try to clarify what a reasonable token of appreciation should cost, said Bélanger. That number could change depending on the feedback submitted by groups like GRIC, PAAC and Democracy Watch, but she said it’s important to set clearer guidelines for lobbyists.

Kerr said the $30 limit would be “be next to impossible” for both the Office of the Lobbying Commissioner and organizations to enforce at receptions where attendees are treated to food and drinks of unspecified value.

Bélanger emphasized the dollar limit is somewhat flexible because the code is a guide, not legislation, so going a few dollars over the limit would not automatically be in breach of the code.

The draft doesn’t specify how many $30 gifts can be given in a certain time frame, and Conacher hopes the commissioner will address this loophole so lobbyists can’t give gifts to officials at multiple meetings throughout the year.

Concerns about the proposed cooling-off periods, $30 hospitality limit and inclusion of working relationships in the commissioner’s definition of “close relationships” were a common thread in many submissions, included those of the National Union of Public and General Employees, Imagine Canada, Counsel Public Affairs Inc, Canadian Labour Congress and Chicken Farmers of Canada, among others.

Deeper problems persist

Even if the draft cooling-off periods were increased and all Democracy Watch’s recommendations were implemented, “secret, unethical lobbying would still be legal” because of loopholes in the Lobbying Act, said Conacher.

The Lobbyists’ Code of Conduct is only binding to lobbyists registered under the Lobbying Act.

The biggest loophole is that only paid lobbyists have to register under the act; lobbyists working for free are unregistered and can violate every rule in the code, said Conacher.

This also means even public office holders who are prohibited from becoming a registered lobbyist for five years after they leave office can still lobby as long as they do it for free, he added.

“If it's a five-year ban when you leave office from lobbying the government, then it should be a five-year ban when you help someone get elected into office,” he said.

A committee is supposed to review the act every five years but failed to do so in 2017. It should be reviewed this year.

NDP ethics critic Matthew Green told Canada’s National Observer strengthening codes and legislation like this is vital to assure Canadians “governments are making decisions in your best interest, not based on the influence of party insiders and former government staffers, or political staffers.”

“A shift towards a more open and transparent government should be a non-partisan endeavour,” said Green.

The new code will hopefully be in place by the end of the year, Bélanger’s office told Canada’s National Observer in an emailed statement.

Comments

Ten years ago, in Québec, « La Commission Charbonneau » examined the influence of fund-raising by special interest groups who lobbied the Charest government and municipalities like Laval (2nd largest city of Qc) between 2003 and 2012. The mayor of Laval received a jail term.

However, it is very difficult to prove influence-peddling in court because no lobbyist will write in a contract « Since I raised money for your political campaign, you owe me a contract¡¡¡¡ ». If we learned any lesson from the «Commission Charbonneau » it is that the rules must be firm and rigid

I agree with you and would like to see subsidizing added to that list for transparent and hard fast rules.

As a senior, I have watched, listened and experienced lobbyists taking over , influencing and reducing our relationship with our MPs. And like the the USA, money talks as all Senators there are millionaires.

Big Oil, especially Big Pharma, and the host of others, 1000s I gave read. So much for democracy when the ears of our elected are beholden to lobbyists

I agree and have found that the only elected official that seems to listen is my municipal government councilor, and that still requires continuous contact.

I feel that you have to join a group whether it is Seniors or a special interest group to get any further.

Our system will never be democratic unless we take steps and make educational investments in it. Lobbyists should be banned. If they do not think so they can at least make each conversation between them and the MPs to be taped and be public information. I have no use for these people and I think they can present their concerns in constituency meetings. That is where everyone else has any influence so why should they be any different? The fact that they have money and power should be irrelevant. The problem is that I am sure many MPs already have to deep deals that makes them vulnerable.

I have always been told that politics is a sticky business, and all you can do is hope that the sticky lobbying people are lobbying your MP to your interests. Sorry to say that in my opinion, money make the system, and the rules.

I know lobbying is an issue that has more grey area than grand dads beard, and I support Democracy Watch for their commitment getting rules laid out to keep an even playing field for everyone. So what this all means to me is that a candidate or elected official is not interested in what I have to say, they just want my vote.

The two thing that I find most disturbing are lobbying and subsidizing, both seem to be out of control and to have transparent and hard fast rules would be a great step forward.