Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

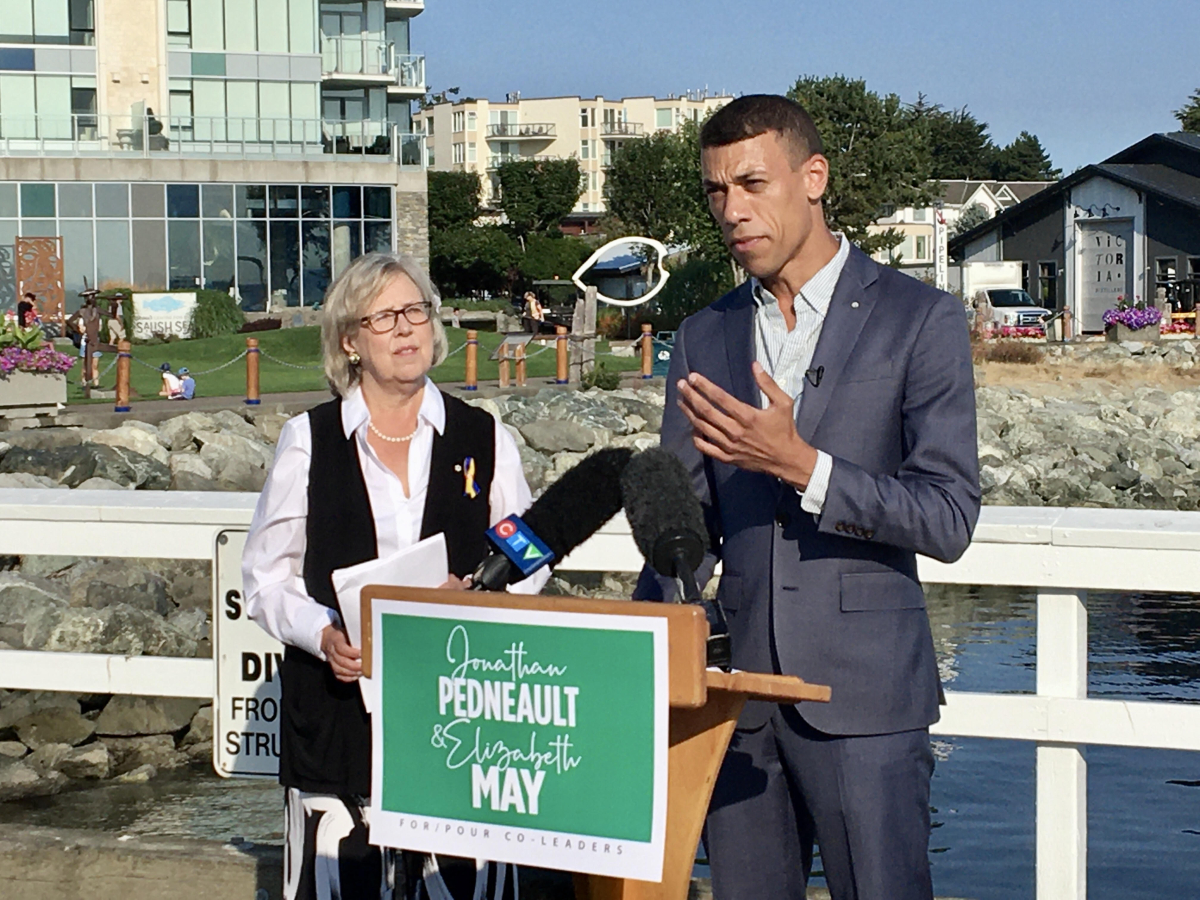

Elizabeth May confirms she is gunning for Green Party co-leadership alongside 32-year-old human rights expert Jonathan Pedneault, who she says should be the “new face” of the federal party.

The pair launched their joint leadership bid, including identical platforms, Wednesday morning in May’s riding of Sidney, B.C.

Their hope is for party members to rank Pedneault and May first and second, respectively, on their ballots. If one of them wins, they will appoint the other deputy leader. From there, the Green Party can have a vote on whether to make a constitutional change to the co-leadership structure.

“That becomes the model that allows us to have what I've witnessed in other countries for Greens: smooth transitions (and) the younger, lesser-known Green usually becomes quite well known,” May told Canada’s National Observer in an interview shortly after the announcement.

Green Party members have an appetite for a new governance structure, said May, pointing to the success of Green co-leaders in other countries like Germany, Scotland, Australia and the United Kingdom, to name a few.

May also expects Pedneault’s ample experience working on human rights issues, his charisma and his comparative youth will attract new members to the party.

“I'm talking to members and I think there's a real thirst and desire for new faces, for new people to come in,” said Cara Camcastle, a political science professor at Simon Fraser University.

Camcastle said she thinks the Pedneault-May partnership is an effort to bring in people with diverse backgrounds because “the Greens have been criticized for being a party that is mainly … white and anglophone.”

May’s status as a “unifier” in the party — inspiring support from the left and right of the political spectrum and everything in between — and her 13 years of leadership position her well to mentor the next generation, said Camcastle.

When May stepped down as Green leader in 2019, she said she had no intentions of running for leader again. But that changed when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a bombshell report on April 4, May said. The grim prognosis hit her “like a ton of bricks.” A few days later, federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault approved an oil project off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador and May said she considered leaving politics altogether to do direct action, but ultimately decided she could have the biggest impact if she threw her hat in the ring and found herself a co-leader.

Camcastle thinks Pedneault’s human rights background will help the party draw vital connections between environmental sustainability and human health and well-being.

Hailing from Montreal, Pedneault worked abroad as a researcher with Human Rights Watch and documented human rights abuses in war zones.

“It became very clear to me, mostly over the past three years, that the state of our political discourse here in Canada was degrading,” Pedneault said of his decision to run for leader. “As I watched these growing tensions in Canada, especially over COVID, I started to get quite concerned actually about where we were headed.”

Last year was an undeniably rough one for the Green Party, with abundant political and financial woes — like Jenica Atwin crossing the floor to the Liberals and Annamie Paul’s rocky leadership tenure. May and Pedneault acknowledge the party is in a rebuilding phase, but say they are not daunted.

“The tensions within the Green Party are not something that scare me,” said Pedneault. “It is complex, but I think collectively, we can not only heal and go beyond that, but also grow and come out stronger… But in order to do that, we need to have a strong, solid team at the helm.”

He says one of the party’s biggest challenges is “looking too much inward” and emphasized the need to quickly address internal issues and focus on the party’s main goal of presenting Canadians with green alternatives.

There are six leadership candidates in total, with Anna Keenan and Chad Walcott running a joint campaign and Sarah Gabrielle Baron and Simon Gnocchini-Messier running as individuals.

Camcastle said it’s smart for candidates to team up because there's more opportunity for people of different races, genders and backgrounds to be represented.

Importantly, these prospective party leaders are from a variety of provinces, not just B.C., she added. In the last election, Keenan ran in Malpeque, P.E.I., Walcott ran in Quebec’s Notre-Dame-de-Grâce—Westmount, Baron ran as an Independent candidate against Erin O’Toole in Durham, Ont., and Gnocchini-Messier ran in Hull—Alymer, Que.

Natasha Bulowski / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments