Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Amid all the fear and uncertainty that defined the first few weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, there was also an undeniable undercurrent of hope.

People stood on their balconies to bang their pots and pans in a show of support for health-care workers. They picked up groceries (and, yes, even washed them) for neighbours at greater risk from the virus. And they gathered in online forums and communities to talk, share and generally pull together.

But after two years of conspiracy theories, fearmongering and the ongoing politicization of public health measures, that shared sense of solidarity is long gone. Our apparent indifference to the scores of children now ending up in crowded emergency rooms and pediatric ICUs is just the latest depressing data point here. Despite hospitals across the country having to cancel surgeries, postpone procedures and even create new ICU spaces for these children, we still seem unwilling to wear the masks that could spare them at least some of their pain and suffering.

As SickKids Hospital CEO Dr. Ronald Cohn told the Toronto Star, “My main message to people is: if you read what is happening, and if you hear what is happening, do the right thing … you don’t need a mandate to wear a mask.”

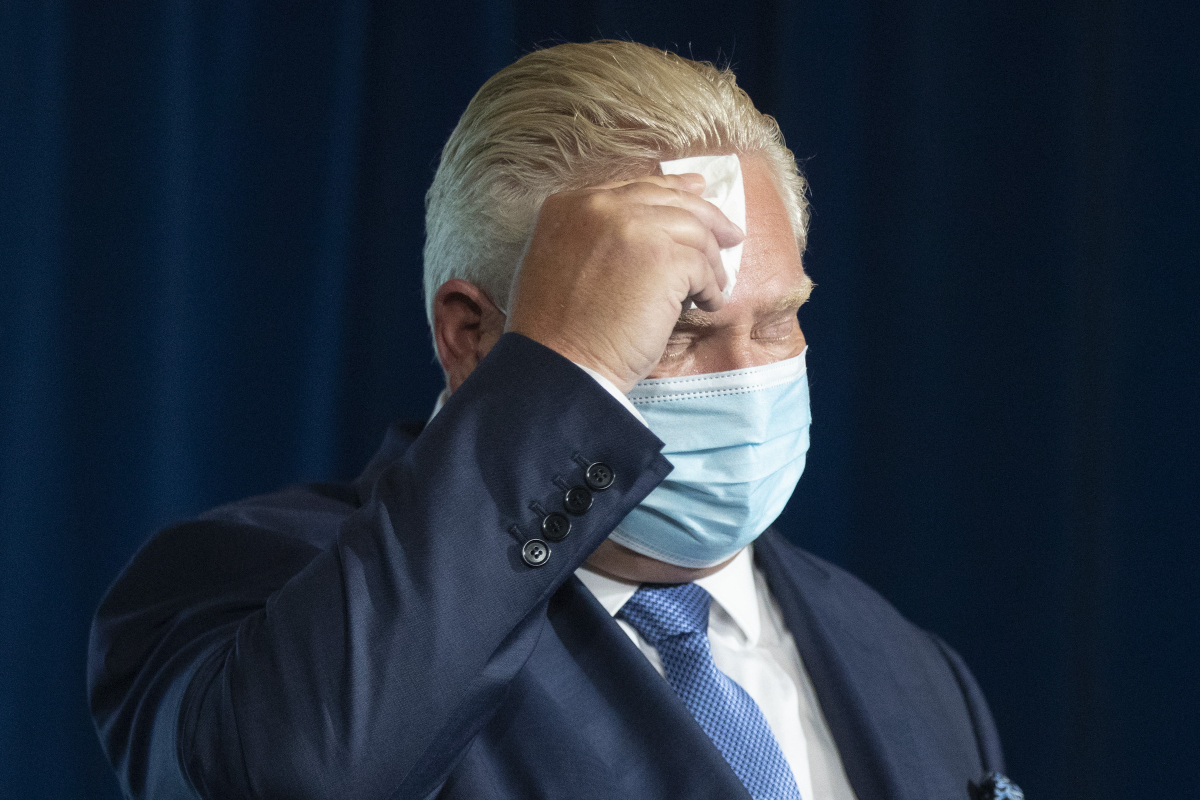

But with all due respect to Dr. Cohn, he’s wrong about that. After all, we’ve been hearing pro-mask appeals from all sorts of public officials and they continue to fall on deaf ears. On Monday, Ontario’s chief medical officer of health said he was “strongly recommending that Ontarians mask in all indoor public settings, including schools and in child-care settings,” while Premier Doug Ford encouraged people to “wear a mask every time possible.” Neither, of course, was willing to actually mandate the measure.

These kinds of cautious interventions are no match for the furious flow of misinformation on social media, and the disparity between the two helps explain why the public seems largely unmoved on this issue. There is an entire digital ecosystem on Facebook and Twitter that seems dedicated to sowing doubt in public health interventions like vaccines and masks, and it rewards the voices that attack them most flamboyantly.

National Post columnist Rupa Subramanya, for example, tweeted a 2019 study showing that respiratory pathogens attach themselves to outer areas of masks in health-care settings, and their volume increased with both time of use and the volume of patients seen. “Masks can actually make things worse,” Subramanya concluded. But this would only be true if the health-care providers in question were licking their masks or eating them after their shifts were over. The very fact that the pathogens ended up on their masks rather than in their lungs is proof that masks do, in fact, work.

Those sorts of facts don’t seem to weigh very heavily on some people’s feelings, though. Neither does the prospect of more children getting sick and ending up in hospital. “There is every indication that this troubling situation is going to get worse before it gets better,” Globe and Mail health columnist Andre Picard wrote in a recent piece. “After all, winter cold and flu (and potentially COVID) season is only just beginning.”

That’s why our elected officials need to step up and do their jobs. Asking people nicely to wear their masks isn’t going to get it done, especially in the face of such concerted resistance. If we want people to do the right thing here, we’ll have to make them — just as we did when it came to other public health interventions, like smoking and seatbelts. That’s especially true in a moment where the sort of “me-first” populism that defined the anti-mandate convoy in Ottawa earlier this year has so thoroughly infected the conservative body politic.

Ironically, if there’s anyone who can turn this ugly tide, it’s actually Doug Ford. Unlike most of his fellow conservative premiers and federal counterparts, Ford has shown some spine in the past when it comes to dealing with anti-vaxxers and other public health scofflaws. He has kicked them out of his caucus, pushed them away from his party and generally struck a more moderate and co-operative tone than people like Jason Kenney or Scott Moe. He has a safe majority government that’s four years away from an election, one that can afford to burn a bit of its popularity in the name of the common good.

And after trying (and so far, at least, failing) to use the notwithstanding clause to choke off the constitutional rights of 55,000 education workers, he could use a good news cycle or two.

Yes, the vocal contingent of anti-mask activists on social media will whine and complain about this intolerable abrogation of their freedoms. Let them. They might even send a convoy to Queen’s Park to rattle Ford’s cage. He should welcome it. In the end, this is about protecting children from sickness, hospitalization — or worse. That’s an issue that any politician with even a hint of a survival instinct should embrace.

And maybe, just maybe, one premier’s decision to show a bit of courage here could be contagious. It could spread to other political leaders, to public health officials, and to leaders in civil society, who might all be emboldened to stand up and say something more forceful than they have to date.

Wearing a mask in crowded public settings for a few weeks is hardly the affront that the loud and selfish would like us to believe. And if there is a slippery slope here, maybe it slides us back to a place where we think and talk as passionately about public safety as we do personal freedom.

But maybe that’s all a pipe dream. Maybe the best we’re going to get is a lot of empty talk from politicians and public officials who are too afraid of their own social media shadows to do anything about the crisis that’s unfolding in our hospitals. And maybe the growing deficit in our shared sense of social solidarity, an unintended consequence of a pandemic that has drained our reserves of trust and community, has become a terminal condition. If so, we’ll need even stronger medicine the next time we face a shared health crisis like this.

Comments

If Ford's goal were to sow enough doubt and mistrust of our public institutions that parents start putting their kids in private school despite the high costs, and the public starts demanding for-profit healthcare, where, if you have the cash, you get served, then it's no wonder he isn't going to mandate masks. This healthcare crisis is then deliberate and calculated.

That's a very interesting comment. Journalists rarely think of back-end payoffs as being part of a politician's motivation but I think that needs some examination. There are significant rewards awaiting a politician who kills unions, public education and public health...and let's not forget how grateful developers might reward someone with a board position or in some hard-to-trace way. Is that happening? I don't know but I do know that Mike Harris is a hero of Dougie's and entered politics as a cranky school teacher and is now a wealthy man.