Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

For John Barton, writing himself into Canadian literature has been solitary work.

“As a queer poet, I feel that I have been ‘doing’ some lonely form of identity politics for 40 years while, at the same time, suffering the mainstream’s reluctance to hear what I have had to say, especially in the early years,” he writes in his introduction of Best Canadian Poetry 2023.

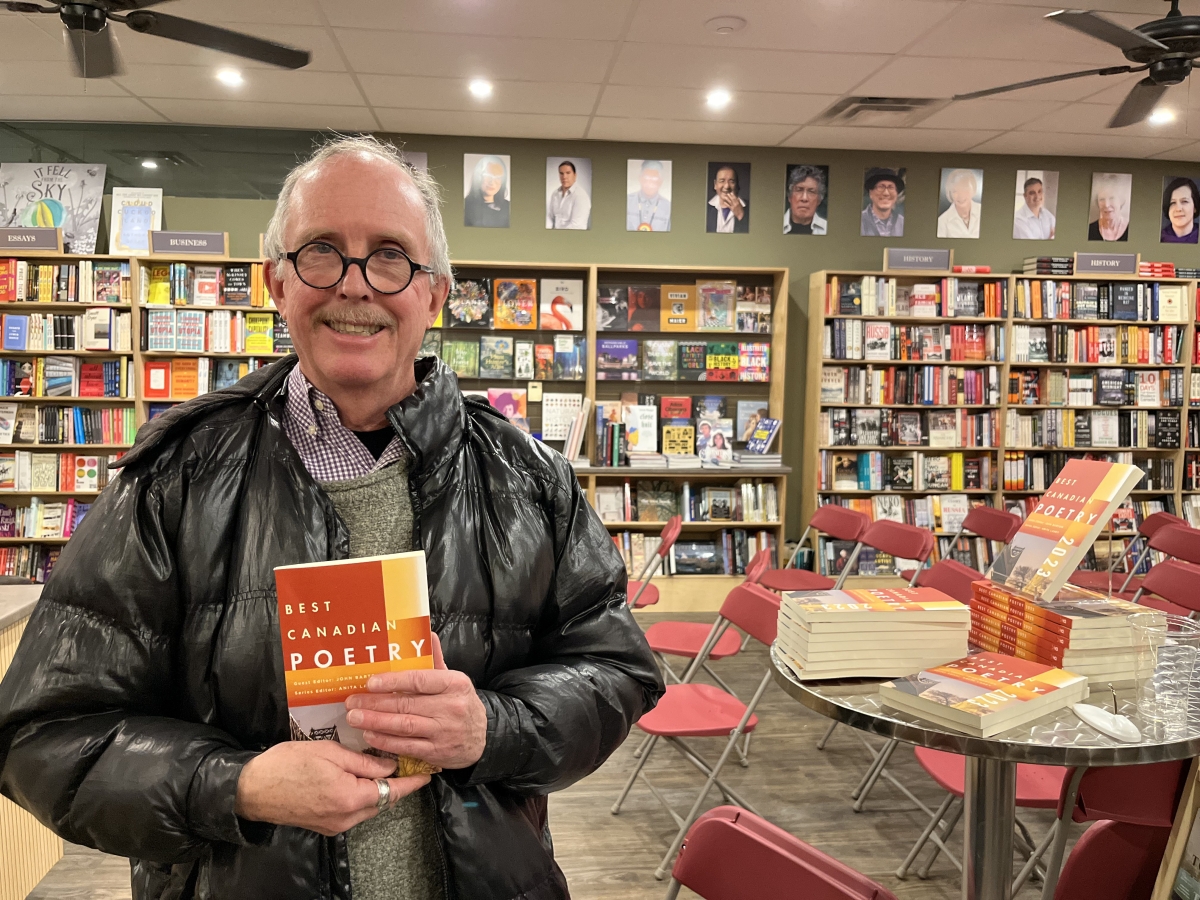

It’s a sentiment shared by his colleague, Armand Garnet Ruffo, whose work appears in the anthology, at its launch, held at Ottawa’s Perfect Books on Nov. 23.

Except, for Ruffo, all you have to do is swap the word “queer” for “Indigenous.”

The Best Canadian Poetry 2023 launch reflected on Barton and Ruffo’s decades of work, the efforts of both queer and Indigenous trailblazers to bring communities once on the margins of Canadian literature to the forefront and the poets breaking new ground today.

In the 1970s, when Ruffo began writing poetry, he was rejected time and again by mainstream literary publications. The only home his work found was in Indigenous publications.

In the lead-up to that decade, Indigenous writers were not given autonomy, as mainstream audiences were reluctant to hear and see Indigenous Peoples in their own words.

Canadian nationalism took over Canadian literature at that time, and it remained a hangover until the ’70s, Ruffo said.

“So if you have an alternative type of voice, then you don’t fit in. These people had an idea of what Canadian nationalism was, and they were sticking to it,” Ruffo added.

“And the nationalism was pretty narrow,” Anita Lahey, series editor for the book, said.

“It was, you’re right.”

For years, Indigenous Peoples were chained to the perspective of the white writer, similar to the way an author might write about an animal, Margaret Atwood wrote in Survival. As the 1970s arrived, Indigenous Peoples were only just appearing in places other than the texts of white writers.

It wasn’t until shortly before (and arguably long after) Survival’s publication in 1972 that Indigenous characters were considered autonomous people, instead of seen only through the white imagination, Atwood wrote.

It took years for a chorus of Indigenous writers to escape that way of being seen, Ruffo said. For him, it was writers like Jeannette Armstrong, Thomson Highway and Thomas King who forged a path in the 1990s.

Now, thanks to Ruffo’s generation, and new Indigenous writers publishing unmuzzled polemics, space has opened up for him to finally “experiment with other forms of Indigenous esthetics,” like his poem in the book, Observed and Observing, That’s Him.

Whether it’s unashamedly Indigenous or queer, this type of poetry is what Barton characterizes in his introduction as “validating rhetoric,” which pushes “hegemony to the curb” and celebrates difference.

It’s in direct opposition to a pleasing, self-confirming type of poetry that “keeps people in their comfort zones,” he added.

For decades, Barton has been writing a form of queer poetry that challenges a discomfort in the reader. It’s an ask, or expectation, for the reader to rise to the occasion of the poem, no matter its language or scenes, Barton said.

“The things that made them uncomfortable, [the reader] should ask themselves why — instead of expecting me to make them feel comfortable on the page,” he said.

As attendees sat cramped between oak bookshelves, listening intently to the readings of Barton and Ruffo, as well as Colin Morton, Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang, John Steffler and Susan Gillis, readers were challenged with distinct poems of varying language, scenes, stories and identities.

The reading — and the anthology — appreciates the overlaps and differences of each poet’s specificity, “so that there’s space for everyone,” Barton explained.

Matteo Cimellaro / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments

I offer a different, "broader" perspective. Firstly, homosexual people are as wonderful as any other people, but are also the minority at this point, at least until and unless all the endocrine-disrupting chemicals change that.

There is no better place to live than Canada as a minority because of our Charter and over the last few decades the general acceptance and appreciation of gay people has truly evolved to the point where they are as mainstream as they will ever be.

A sort of fretful contradiction has arisen now when they balk at still not being "mainstream" enough while simultaneously projecting a preference for "special," read "superior" status. The reason a lot of people don't sufficiently gravitate toward or appreciate poetry about being gay, for example, is mainly because they are NOT gay and so lack interest. Hectoring readers for being uncomfortable with what seems to boil down to their sexuality, especially considering the machinations of gay sex ignores the fact that a lot of people simply don't consider that particular context appealing even with heterosexuals.

To my "broader" perspective, if you primarily balk at your minority status and want more power, maybe perceiving that the top job is still not open to you, that' it's still more likely to go to a white heterosexual man, well then as a woman I say get in line. We're in the same position relative to that reality, have always been, are still fighting for parity, but are also NOT a minority, comprising half of the population.