Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

In the summer of 2021, the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru gave the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the body that regulates international seabed mining, two years to complete regulations governing the new and contentious deep-sea mining industry.

With the deadline on the horizon, Episode 11 of Hot Politics tackles why some countries and mining companies want to harvest the bottom of the ocean and what impacts that will have on ecosystems that deep.

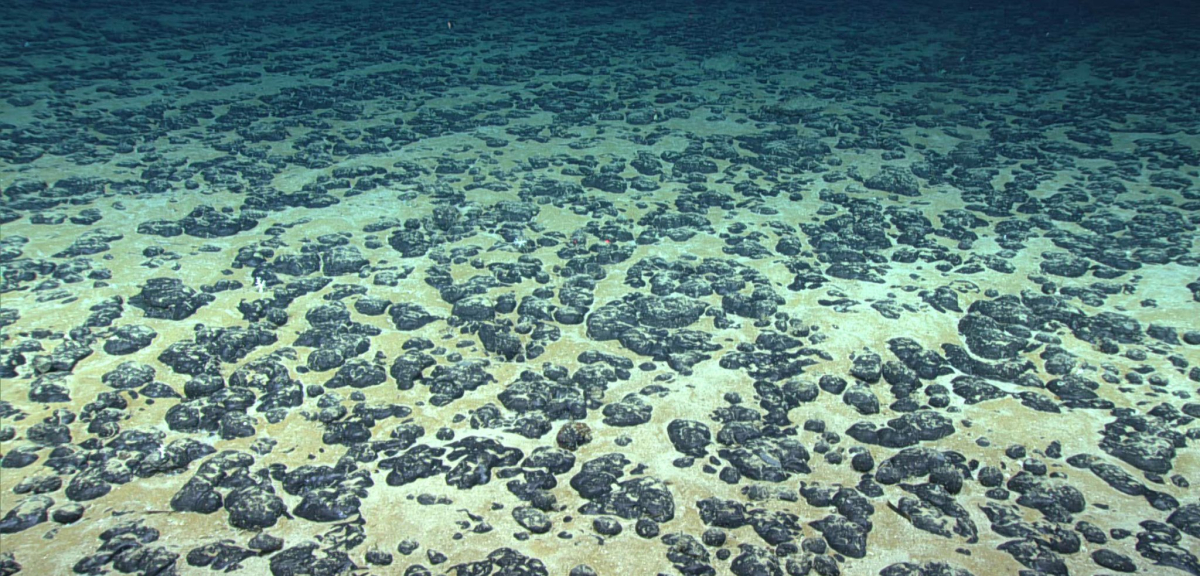

Host David McKie talks with environmental biologist Ken Nealson, who explains polymetallic nodule collection. The nodules are potato-sized rocks on the seafloor that contain essential metals such as cobalt, copper, nickel, and manganese — all needed in electric battery production.

He says no one knows the consequences of deep-sea mining. “You can't really prove that there's no collateral damage until you get the thing down there,” said Nealson.

Gerard Barron, CEO of The Metals Company, has already sent a team to the middle of the Pacific Ocean to do exploratory work with robotic equipment. Barron calls the area where the tests were done an “abyssal zone” where only bacteria survive.

“Surely, it makes sense to be carrying out extractive industries in parts of the planet where there is the least life, not the most life,” he said.

Barron argues the impact of his company’s mining practices is a fraction compared to the alternatives on land. The energy transition seems impossible without vast quantities of metals that could replace fossil fuels, he said.

“I think it's easy for our opponents to sensationalize deep-sea mining by looking at what happens on land and encouraging people to think we're going to do this in the ocean. Now, that is a totally different thing,” said Barron.

James McFarlane, the former head of the office of resources and environmental monitoring for the ISA, has concerns about Nauru’s demand for regulations by this summer. McFarlane is doubtful any meaningful environmental impact assessment can be done by then.

“The foundational work that's required to understand the environment that's going to be exploited is really not completed. We've done a better job of mapping the surface of the moon. We've done a better job of mapping the surface of Mars. We've got more data there than we do in the deep ocean,” he added.

Want to learn whether deep-sea mining could be a new frontier or the next environmental disaster? Tune in to the 11th episode of Hot Politics — on Apple Podcast or Spotify.

Hot Politics is made possible by listeners like you. If you’ve supported the podcast already, thank you. If you haven’t, click here to donate what you can to help us keep producing valuable journalism.

Got questions or comments? Email us at [email protected].

You can also follow us on Twitter @NatObserver.

Comments