Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

An online form and $58.75.

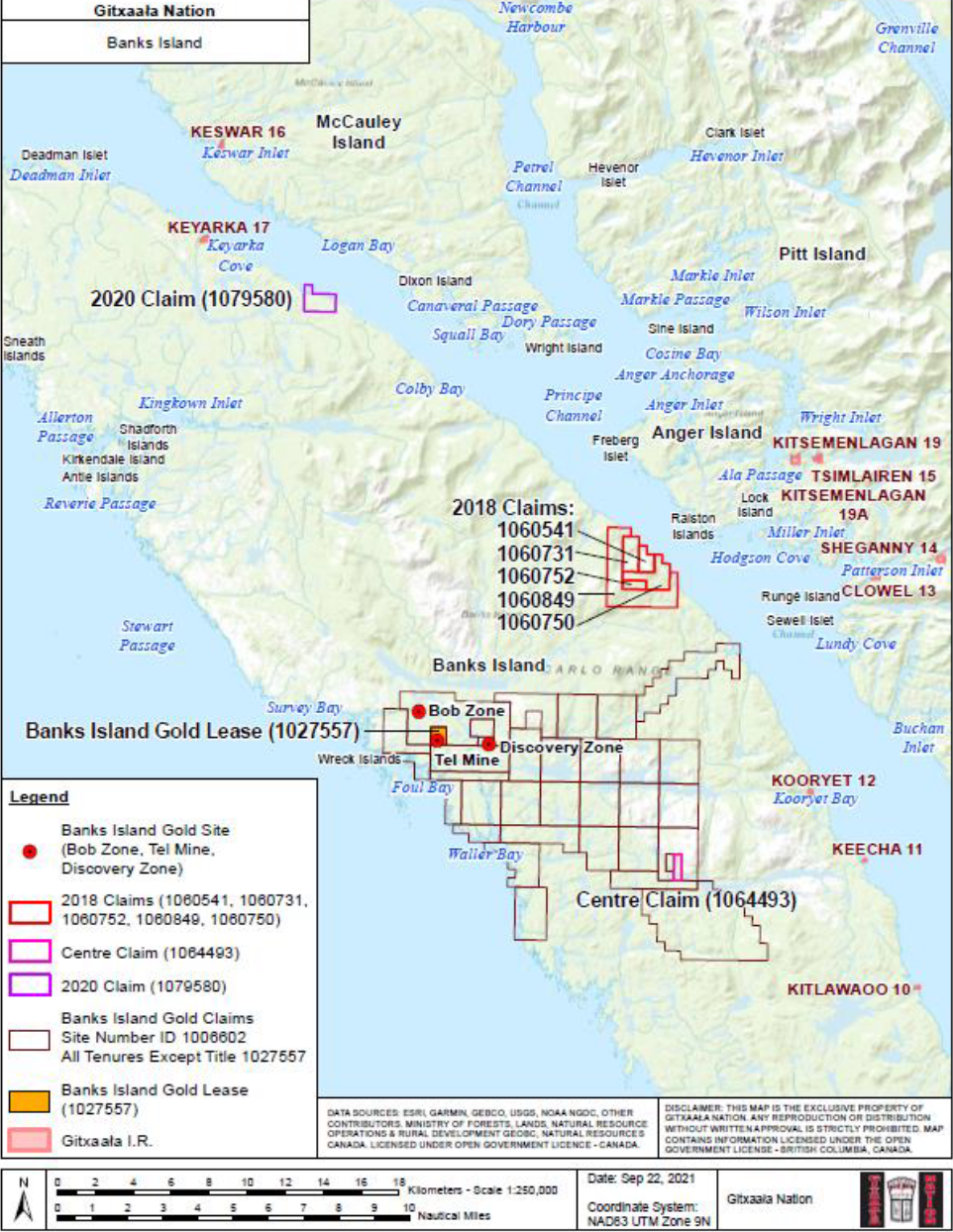

That is what it takes to claim a mining stake in the traditional territory of the Gitxaała Nation, according to a written submission to the B.C. Supreme Court. At no point in the process does the mining claim, accessed through a provincial portal, ask the individual or company applying for it to consult with the nation.

For this reason, the Gitxaała Nation is challenging B.C.'s Mineral Tenure Act in a case that will test whether the province's legal commitment to recognizing the rights of Indigenous Peoples has the teeth to change laws.

Located on the northern coast of British Columbia, the nation bases its legal challenge on the province’s 2019 Declaration of Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (DRIPA), which enshrines the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in B.C. law. DRIPA was the first law in Canada to adopt the international declaration outlining the rights of Indigenous Peoples around the world.

It’s also a case to watch across the country, given the similarity of language between DRIPA and the federal bill that enshrined UNDRIP into law in 2021.

“Presumably, it would be very persuasive to other courts, considering the federal legislation,” Jessica Clogg, one of the lawyers representing the Gitxaała Nation, told Canada’s National Observer.

B.C.’s Mineral Tenure Act was passed during the Gold Rush in the late 1800s and remains a colonial carryover, Clogg said. It’s hardly changed; in fact, it has become easier for mining claims to be made. In the past, free miners would have to physically put a stake in the ground to be authorized by the Crown. Now, with a few clicks on an online portal, stakes can be made from the comfort of a desk, Clogg explained.

It’s like Amazon for mining claims, but instead, it’s even “easier,” Clogg said. “It’s automatic, you don’t even have to wait for delivery.”

The Gitxaała Nation argues the Crown fails to consult with the Gitxaała Nation when issuing these mining claims. The court challenge comes on the heels of the 2015 Yellow Giant Mine tailings breach, in which wastewater flowed into a nearby creek for six weeks. Samples of the water exceeded health guidelines for arsenic, lead and mercury, among other contaminants. The spill has resulted in $2 million worth of cleanup costs. The mining company responsible went bankrupt, and the site has still not been remediated, according to the Gitxaała Nation’s written submissions to the court, which Canada’s National Observer has viewed.

A large portion of the written submission from the Gitxaała stresses the importance of the traditional laws of the nation, ayaawx. Linda Innes, elected chief councillor of the Gitxaała Nation, repeats a word used by the Elders of the community regarding those traditional laws: łhumts, or respect, which the province has breached in the nation-to-nation relationship by not obtaining free, prior and informed consent from the nation to grant mining claims.

Innes describes seeing old, empty oil barrels, trash and other litter around her territory from mining exploration. In 2015, the community was unable to harvest after the Yellow Giant Mine tailings breach. Without harvesting, the community is unable to hold its ceremonial feast, which is one of the most important ceremonies for the traditional laws and language transfer of the Gitxaała nation.

“When our title is claimed or staked away without our consent, it erodes our governance. And then when there’s environmental destruction, it erodes our way of life.”

Innes described her territory as beautiful. On any given day, you’ll see the whales around Banks Island, or lax k’naga dzol.

“It's a live place to be,” Innes said.

Matteo Cimellaro / Canada’s National Observer / Local Journalism Initiative

Comments

I approve of this from a strategic perspective. Mind you, from a tactical perspective, if it's that cheap and easy, maybe First Nations should just pre-emptively place their own claims on all the bits of turf they care about most. You could probably lock up all the most important places for less than the cost of a single lawsuit . . .