‘Revolving door of teachers’ hurts everyone at First Nation schools

Lawrence Wesley Education Centre in remote Cat Lake, a fly-in community 400 kilometres north of Thunder Bay, is a well-equipped school, with new Smart Boards, a new gym, a library and a computer room and a cafeteria large enough for all the students to eat together.

Yet, the beginning of the school year puts Cat Lake First Nation in scramble mode. Teacher positions still need to be filled while students have already begun classes. Lawrence Wesley Education Centre was built in 2015 and could compete with any other school in the south with how it is resourced and outfitted — that is, except when it comes to teachers.

It’s almost a yearly occurrence, said Skyler Oombash, Cat Lake’s councillor who holds the education file. And Cat Lake is not alone.

“Everybody’s short on teachers — sometimes it’s hard to find teachers to work up North,” Oombash said.

For First Nations in remote communities, finding and retaining teachers is a difficult task and only hurts the educational development of students. Conditions like social isolation, a high cost of living and some infrastructure problems complicate the picture. It’s reached a near-crisis point, and Ottawa, Queen’s Park, and municipalities need to step up to help schools.

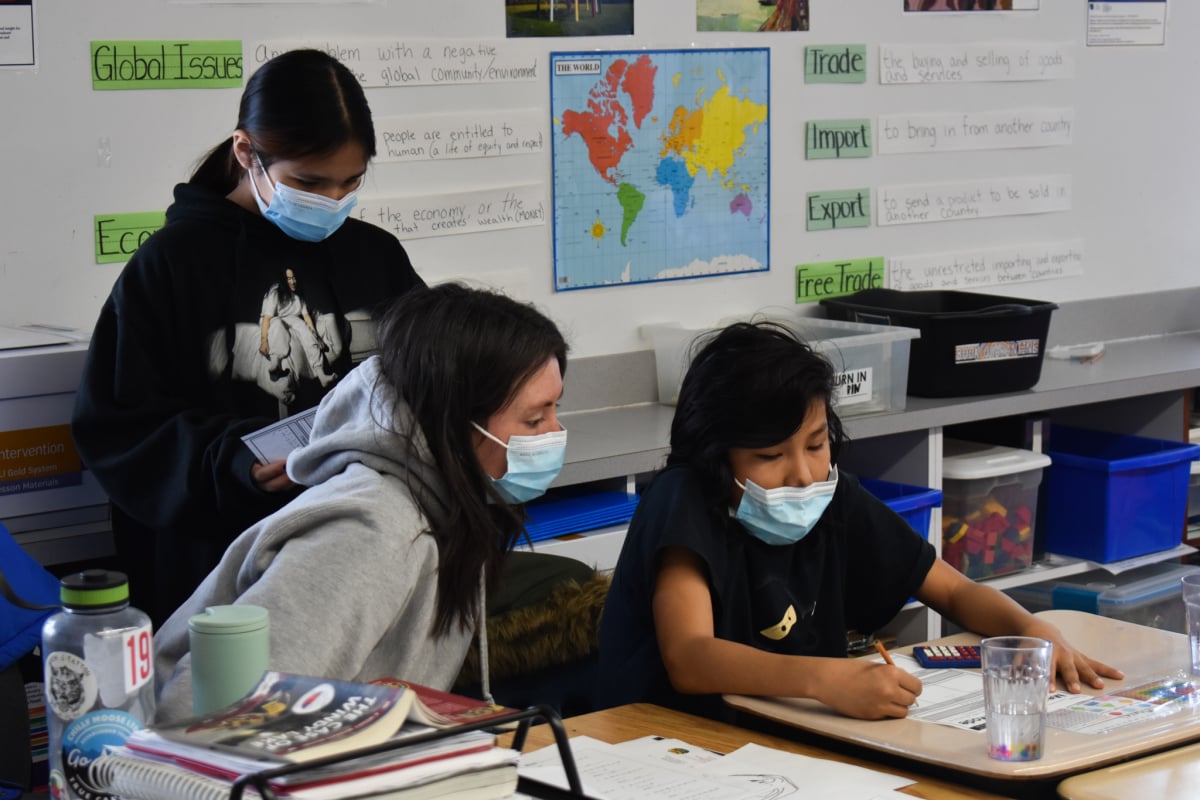

Chapter 1: High teacher turnover leads to low student engagement

While schools in the south might have teachers who remain for decades, turnover is, on average, two to three years at First Nation schools in the North, Sharon Nate — executive director of Matawa Tribal Council, a subsidiary of a First Nation tribal council that represents 12 First Nations in northern Ontario — told Canada’s National Observer.

It’s a widespread crisis across northern First Nation communities that requires an all-hands-on-deck approach, Ken Sanderson, executive director for Teach For Canada-Gakinaamaage, said. His non-profit works with northern First Nations to recruit, prepare and support teachers who make the minimum two-year commitment to teach in a northern First Nation community.

“We need governments to step up, we need universities to step up, and we need the public system to step up,” he said.

Many factors impact a child’s development, but one of them is consistency in their educator, Sanderson said. With a high turnover of teachers, a student can struggle to become engaged and grow exhausted with the relationship-building process integral to the student-teacher relationship.

“If you have a revolving door of teachers coming in — never mind year after year, but midway throughout the year — you can't form those trusting relationships,” Sanderson said. “It becomes difficult for children to become excited about lessons and learning.”

In Canada, only 69.9 per cent of First Nations members have a high school degree compared to 82 per cent for the rest of the population of Canada, according to the 2021 census. For those in northern remote communities, that number can be higher. In Cat Lake, around one in five working-age members has completed their high school education, but graduation rates are rising, Chief Russell Wesley said.

In Cat Lake, teacher retention remains an issue, save for three longtime staff members, and students are falling behind in their literacy skills, Oombash said.

Cat Lake is exploring recruiting and paying community members as tutors to provide a stopgap for the lack of action from the federal government, the province and universities. Cat Lake hopes to have its program up and running in the fall.

Teach For Canada—Gakinaamaage similarly supports First Nation schools by engaging local teacher assistants in First Nations through training and professional development.

It’s an echo of the ideal situation where teachers would be from the community, Sanderson said. But that’s not the reality — even in larger First Nations, recruiting has to come from outside, often from the southern parts of the province.

“There's always this need to find people to recruit, to teach, and you don't just want to find just anybody, right?” Sanderson asks.

Take Beth Shaw and April Whalen, who are working in Big Grassy River First Nation in Ontario. Both knew they wanted to work in a First Nation when they graduated from teacher’s college. The couple started working in the community four years ago and have found a rhythm and deep connections in Big Grassy River.

“We've really taken the time to build those connections within the community and with the kids, and it feels like you know them and the families,” Whalen said.

“You can see what the consistency has done for the school because it takes time to build that trust and ability to work all together cohesively,” Whalen added, pointing to her fellow school staff.

Both Cat Lake and Big Grassy are small, tight-knit communities where the slightest changes like a new car can set off conversations throughout town, Shaw said. That’s why it’s so important to build connections because “everybody is family here,” Whalen added.

Chapter 2: Housing, social isolation and the high cost of living

Back in Cat Lake after March break, Lawrence Wesley has settled down again after another scramble to find teachers following an exodus over the Christmas 2022 holidays. Lawrence Wesley Education Centre lost three of its eight teachers over that period alone.

Teacher retention is a yearly struggle, said Oombash, sometimes throughout the entire school year. Since Christmas, two of the three teaching spots have been filled, but Lawrence Wesley remained shorthanded without a fully functioning Grade 4 class for weeks on end.

Lawrence Wesley sits in a clearing of trees down a winding road past the new subdivision in town. Dogs run about, gnawing at stacked framing lumber near the contractor’s lodging. When the school was built, temporary housing was erected for labourers. The homes are small — trailers, essentially — with two or three bedrooms and a small living space.

They weren’t designed or built to be long-standing accommodations, Oombash said. But they became teachers’ housing anyway because all the new housing is prioritized for community members to escape the remaining homes plagued with black mould.

Over the past years, some of the furnaces in the teachers’ quarters have broken down. Without heat in winter, when temperatures regularly drop below -30 C, the teachers were in a precarious situation. It’s part of what makes teacher retention so difficult, Chief Wesley said.

Sometimes it’s not the heating that’s the problem. Sylvia Wesley, a kindergarten teacher at Lawrence Wesley Education Centre, reels off a shopping list of deficiencies. The electrical wiring needs work (some outlets aren’t functioning), and the trailers need new dishwashers, sinks and toilets. In a word, they are getting old, she said.

Cat Lake is looking for ways to improve or build new teachers’ quarters, but funding is tight, Oombash said. Repair costs are steep, and equipment is hard to transport to remote First Nations like Cat Lake. There is no Home Hardware in town to purchase a new furnace. Supplies must be flown in or transported on the winter road, which only operates from January until the spring thaw. On the winter road — a maintained frozen pastiche of lakes, rivers and mud paths — it can take up to four hours to reach the closest central hub in Sioux Lookout and another four hours to get to Thunder Bay. When heavy appliances, such as new furnaces, have to be flown in, costs can rise steeply.

Even with the community’s housing problems over, the isolation can prove too much for some teachers unaccustomed to living in a fly-in community of fewer than 500 people, said Wesley, the kindergarten teacher.

“People need to recognize that you’re removing yourself from family and friends … there’s a loneliness factor, there’s a whole bunch of this that I don’t think people always understand that is at play,” Sanderson from Teach For Canada—Gakinaamaage said.

Teachers don’t really know what they are getting into when they take the job, Wesley said. They come with good intentions, thinking they can handle living so far north. But once the isolation sets in, it sinks in that the community has only one store and a handful of streets, and the only choice for a weekend getaway is a pricey plane ticket to Thunder Bay.

“It's like BOOM, they come here and,” Wesley pauses, “OK.”

Most teachers come from away, some even from other countries. Cat Lake has had three teachers from Lebanon and another from West Africa.

There is some homegrown employment, however. Teacher assistants are hired within the community, and those workers just received a pay raise from minimum wage to $17.50 an hour. The nation’s leadership hopes to bump that to $20, due to the high cost of gas and groceries at the Northern Store, which is not owned by the community, but instead by the North West Company, a carryover from the colonial presence of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Groceries in a fly-in community are expensive: a box of juice hovers at around $9, a box of pasta at $10 and a bag of salad over $11. At the Northern Store, the only shop in town, teachers have to pay exorbitant prices for fresh foods compared to what they pay down south.

Chapter 3: Better incentives and community direction

All of this leads Wesley to believe teachers should be paid more.

Salaries currently range between $40,000 and $100,000, with the average wage of around $50,000 for early career teachers in northern First Nations, according to Teach For Canada—Gakinaamaage.

However, these regions incur higher costs for retaining teachers, resulting in the need for better compensation and higher investments for remote First Nations to expand and sustain their education programs because “it’s about equity,” Sanderson said.

First Nation Education organizations often cover a teacher’s accommodation. Still, the costs to visit family over March break or Christmas can stretch into the thousands of dollars. Sanderson jokes it would be cheaper to fly his team to Hawaii for a meeting than to a northern First Nation.

Teach For Canada—Gakinaamaage also provides up to $4,000 in allowances and usually two round trips in and out of the community for teachers, enough for the beginning and end of the school year.

But Wesley thinks the starting salaries need updating to offset the high cost of living and ensure teachers can access fresh fruits and vegetables.

“It’s hard to get what you want in the community,” she said, so some teachers choose to leave.

“When teachers leave, the teachers here struggle,” Wesley said. “It stresses us out because we have to take over their duties and we're burnt out.”

However, not all teachers leave early. Some fall in love with the community and stay for their entire career, but there are only two teachers like that in Cat Lake: Wesley and another teacher from the south who has been in the community for 17 years. But she acknowledges: “It's hard to find people like that.” In the North, those teachers are often the exception, not the rule.

For Sanderson, it’s about finding the right people, like Shaw and Whalen, who are ambitious enough to take on the learning experience of teaching in a First Nation community.

But for that to happen, there have to be incentives. Sanderson points his finger at Ottawa to create a loan forgiveness program for teachers graduating from university. If they are willing to move to a remote First Nation to teach for a sustainable number of years, governments ought to seriously consider that, he said.

It’s not unheard of. The federal government runs a loan forgiveness program for nurses and family doctors working in underserved and remote communities for a year.

“We are at a crisis point with First Nation education that it is warranted to set up a program like that,” Sanderson said.

A previous version of this article stated that Teach For Canada—Gakinaamaage pays for accomodation and is developing a tutoring program in Cat Lake. In reality, First Nation education organizations often pay for accommodation, and Teach For Canada—Gakinaamaage supports First Nation schools by training and developing teacher assistants hired within the community.

A previous version of this article described Beth Shaw and April Whalen as friends when they are, in fact, partners.

Comments

Money talks, free housing, BUT, the 2 things first nations lack! A sorry situation

Thank you for another insightful report about the challenges of indigenous communities in NWO.