Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The federal government has released an action plan on how it will implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The release of its United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA) on Wednesday was timed to match National Indigenous Peoples Day, two years after the legislation received royal assent.

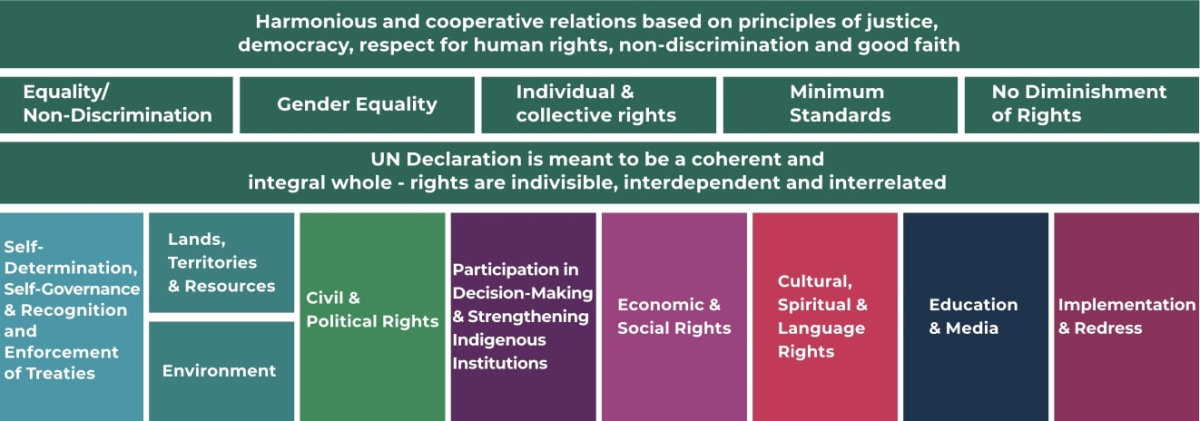

UNDA, which contains articles describing a wide array of collective and individual Indigenous rights, will have implications for every federal department. There are also over 700 federal laws in Canada and all of them will be impacted by the implementation of UNDRIP, a Justice Canada official said on background at a technical briefing on Wednesday.

Much of the document commits to a path forward, including developing mechanisms for accountability. But much remains unclear as to how these actions will manifest in policies and what sway they will have over resource projects, modern treaties and dismantling of the Indian Act. It’s why federal Justice Minister David Lametti calls UNDA an imperfect evergreen roadmap for implementing UNDRIP into Canadian law and policy.

Here are three sticking points to watch in UNDA’s action plan.

What is the definition of free, prior and informed consent?

Free, prior and informed consent is one of the central doctrines of UNDRIP, allowing nations to give or withhold permission to develop in their territories. However, it’s an ambiguous concept when a nation-state’s sovereignty, like the Crown, cannot be disrupted.

There is no mention of First Nations having veto power over natural resource projects in the UNDA action plan, keeping pace with what Ottawa has said in the past. Without a veto, it’s unclear how free, prior and informed consent will be defined going forward when industry and provinces are involved.

Ottawa is not in the position to define free, prior and informed consent, a Natural Resources Canada official told Canada’s National Observer. However, industry and Indigenous partners are interested in a definition.

Ottawa is in a position to bring all interested parties together to develop expectations around free, prior and informed consent for the development of projects, they explained.

The concept also stretches beyond natural resources, including participation in decision-making processes and modern treaty rights. The official notes there will be no one-size-fits-all definition.

Natural Resources Canada is committed to creating a process that will help define the parameters of free, prior and informed consent, the justice minister said at a press conference on Wednesday.

“I think you can expect a framework in the future,” Lametti added.

Provinces without an UNDRIP act remain a big question mark

B.C. is the only province that has enshrined UNDRIP into law and crafted its own action plan with DRIPA. The rest of the provinces remain a big question mark.

The UNDA action plan pertains only to federal legislation, including federally regulated industry.

Government officials maintain that they expect the feds will be able to bring the provinces and territories alongside over time, citing UNDA as “generational work.”

In 2020, when the federal government tabled the UNDRIP legislation, six provinces objected: Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and New Brunswick.

With UNDA’s action plan released, Lametti hopes the provinces will work with Ottawa to adopt the principles of UNDA, “whether formally or informally,” moving forward.

“We’re leading by example here,” he added.

It’s a significant sticking point given that the largest owners of Crown land are the provinces, which means they have a majority of jurisdictional power over natural resource development.

How will Indigenous Peoples and their communities be involved in the economic participation of natural resource projects?

UNDA includes sections on increasing this involvement.

Yet, it’s unclear what actions the feds will take and what that participation might look like.

Natural Resources Canada is developing a national benefits-sharing framework that will include measures like increasing Indigenous capacity to participate in projects, as well as increasing access to affordable capital, according to documents obtained through an access-to-information request.

Also, $25 million has been earmarked to engage and build Indigenous capacity to support participation in the critical minerals sector.

Matteo Cimellaro / Canada’s National Observer / Local Journalism Initiative

Comments

I expect that when it comes to other things, both Mr. Trudeau and Mr. Lametti understand what "free, prior and informed consent means.

They know what it means, FI, when they go to a doctor, and treatment, say surgery, is what the doctor recommends. They know they can refuse the suggested treatment. They know they have a right to ask what other measures are available, and to be have full information as to the processes, risks and expected outcomes.

And because they are Mr. Trudeau and Mr. Lametti, they have every reasonable expectation of exercising their right to consent -- or to withhold consent. Withholding doesn't matter that the doctor and the hospital and whoever all else get to decide, over their heads, what to do outside the conditions of consent.

However, poor people and others the people within the medical system decide are somehow not entitled to exercise their rights, get something else.

I'm just saying that those who have power over are quite used to treading heavily on the rights of those who don't. And that is the position that First Nations peoples have been in for a long time. It looks to me like governments are quite determined to make sure that position is maintained.

I'm sorry: being able to have some of the proceeds of acivity that ruins their lands, their health, and indeed *everyone's* health ... isn't consent and it isn't reconciliation, in any way that I understand reconciliation. Then again, what do I know.