Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A widespread plague of the dreaded “zombie deer disease” in B.C. can only be controlled by ramping up surveillance, testing and disposal methods for infected animals, wildlife experts say.

Fast action is needed to halt the spread of chronic wasting disease (CWD), especially in remote rural areas where people rely heavily on hunting for food, said Jesse Zeman, executive director of the B.C. Wildlife Federation.

The disease destroys the nervous system of cervids like deer, moose, elk and caribou, leaving them skinny, stumbling, dazed and drooling in its late stages, and it is almost impossible to eliminate once it infects wild populations.

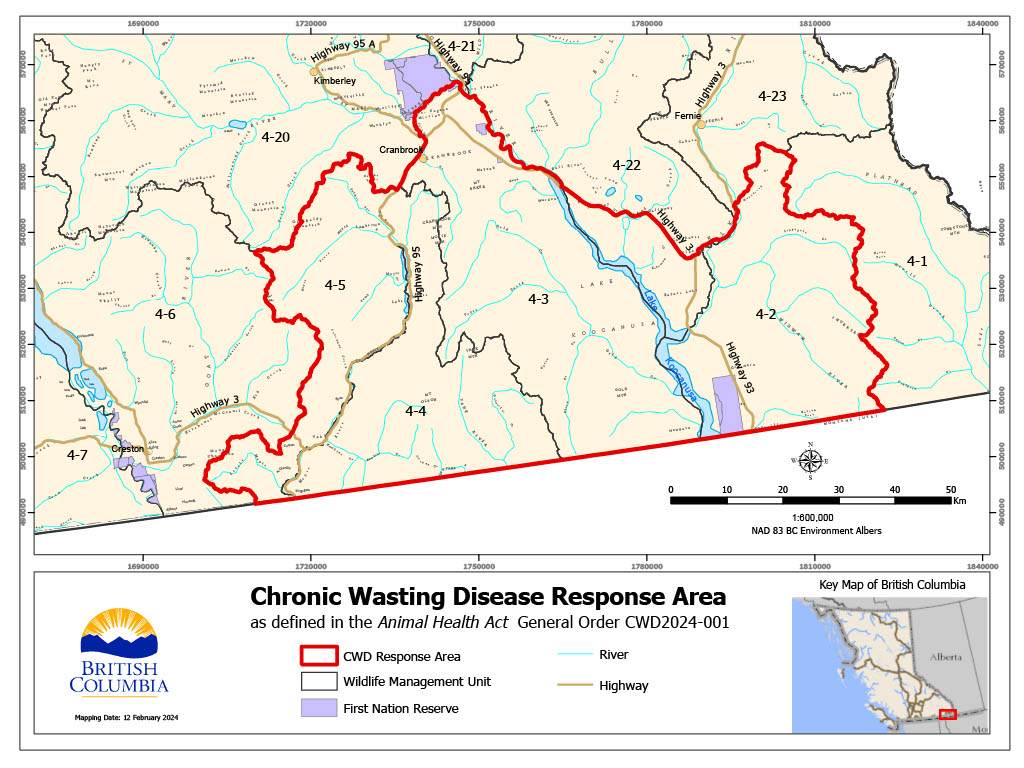

CWD had already spread to the Prairies and south of the border but was detected in B.C. for the first time early this month in the Kootenay region south of Cranbrook.

Now that it has arrived, the province can no longer afford to shortchange testing and monitoring efforts, Zeman said.

The disease spreads easily through animals’ saliva, urine and blood and is tenacious once it enters the soil or environment and can be transported far and wide as animals roam across the landscape, Zeman noted.

Ramping up efforts and investment to monitor and test for the disease is going to be key to contain transmission and any impacts, he said, adding B.C. underfunds the management of wildlife threats.

The province’s CWD program gets $200,000 in funding, according to the 2023 CWD response plan.

B.C. has created new rules that make CWD testing for all harvested cervids compulsory and restricts the transport and disposal of any road-killed deer, moose, elk and caribou in the immediate area where the first cases of the disease were confirmed.

The new rule builds on a 2019 regulation requiring hunters to submit the heads of just deer harvested in high-risk areas along the borders in the southeast Kootenays for testing after nine cases of CWD were discovered near the border in Montana.

Hunters are also encouraged to drop off the heads of any cervids, regardless of where they were harvested, at freezer depots located around the province where samples are collected and sent out for testing.

However, some hunters who turned in animal heads for testing in October are just getting results back now, Zeman said.

“It’s completely unacceptable to take four months to get test results back,” he said, noting many hunters rely on wild game for their food security.

The CWD samples are sent to a lab in Alberta for testing, where they are considered a lower priority than local samples. The CWD response plan recommends a lab be set up in B.C. if the disease arrives in the province.

In 2022, a little more than 1,000 heads, most from deer, were submitted to depots for sampling and testing.

Long waits for results will stymie efforts to limit the spread of the disease, Zeman said. And as new mandatory testing regulations are introduced, the volume of tests and the lag time are bound to increase, he added.

Most freezer depots are concentrated in the B.C. Interior and there are none on Vancouver Island.

Health authorities, however, warn people not to eat meat harvested from high-risk areas until test results come back negative.

There’s no record to date of CWD being transmitted from animals to humans.

However, it belongs to the same class of diseases as mad cow (Creutzfeldt-Jakob) disease — another type of fatal prion degenerative brain disease — that jumped from cattle to humans.

There are also currently no specialized disposal facilities or incinerators to deal with carcasses or meat confirmed to be tainted, Zeman said.

Although animal remains can be buried in a dump safely at specific depths, there’s no framework for that practice, and some dumps refuse to take them.

It also poses a serious conundrum for hunters, who typically leave unused animal remains on the land as food for other animal scavengers.

Animals may be sick without showing any symptoms, so leaving potentially infected remains on the landscape may contribute to the spread of the disease, but so could transporting remains elsewhere if they can’t be disposed of safely.

The implications are just beginning to set in and the wildlife sector and province will need a beat to determine the next steps, but significant changes will be needed by the hunting season in the fall, Zeman said.

“Everybody's gonna have to take a step back and ask, ‘How do we minimize or mitigate how fast it spreads?’”

- Anyone seeing cervids displaying symptoms of chronic wasting disease should call B.C.’s RAPP line at 1-877-952-7277.

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments