Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Canada’s largest banks are deeply entrenched in fossil fuels, having pumped at least $1.2 trillion into the sector since the Paris Agreement was signed in late 2015. But it’s not just their investments and lending that are increasingly under scrutiny –– it’s their leadership, too.

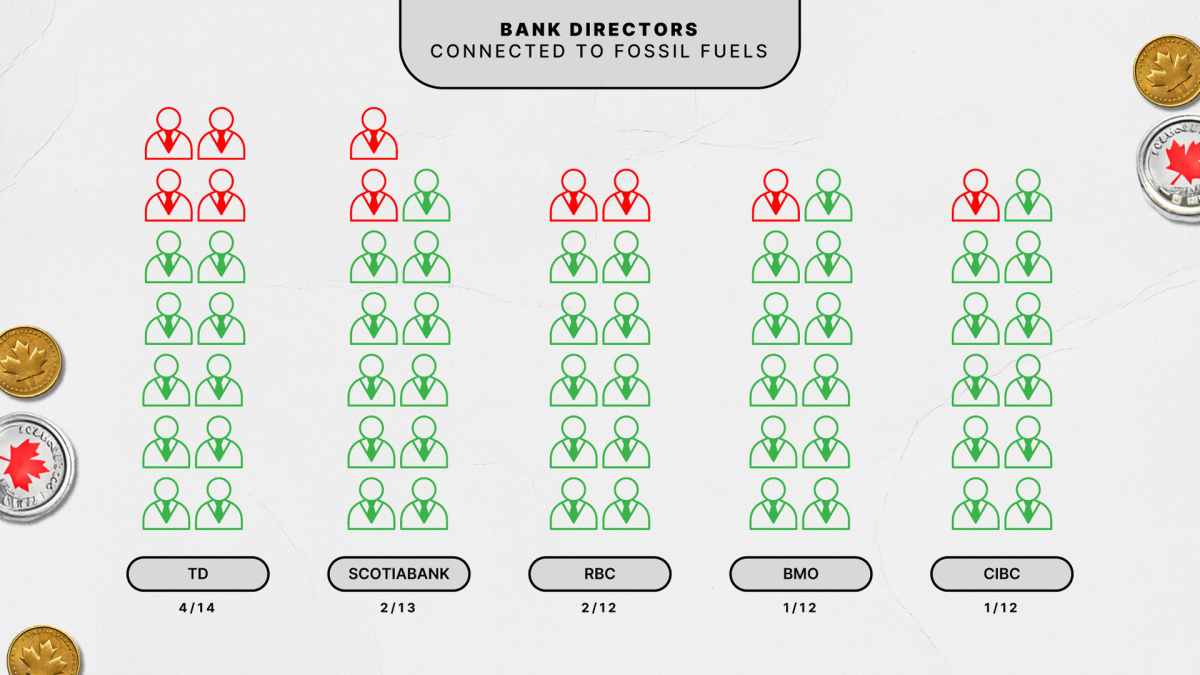

RBC, Scotiabank, TD, BMO and CIBC are each governed by a board of directors, and several of their board members also sit on the board of a fossil fuel company. For climate advocates, this raises serious questions about potential conflicts of interest and speaks to the need for government intervention.

A 2022 investigation from Canada’s National Observer revealed one in five bank directors also sits on the board of fossil fuel companies such as Enbridge, TC Energy and Capital Power. As previously reported, those connections could also represent a violation of the director’s legal obligations to act impartially in the bank’s best long-term interest, given the threat of climate change means fossil fuel assets could become worthless.

Two years later, not much has changed. Canada’s National Observer combed through how bank boards have shifted in the past two years and found approximately 17 per cent of bank directors also sit on fossil fuel boards.

Practically, these connections mean fossil-linked directors must act in the best interests of both a bank and a fossil fuel company at precisely the same time the world must transition away from fossil fuels to protect the planet.

Specifically since 2022, RBC added one fossil fuel-linked director, while Scotiabank decreased by two and BMO decreased by one. TD and CIBC remained unchanged.

BMO, TD and Scotiabank did not return a request for comment. Spokespeople for RBC and CIBC pointed to existing conflict of interest and environmental, social and governance (ESG) policies at their respective banks, but did not answer questions about why climate expertise is not present on their boards.

Serving on multiple boards at the same time is entirely legal, and for banks, having representation from major sectors of the economy is important. But with fossil fuel-linked directors evaluating the risks of climate change and climate-related legislation, climate advocates are concerned the coal, oil and gas sector is wielding influence over Bay Street and preventing the country from aligning the financial sector with climate goals.

For climate advocates, the slight step down is not evidence of banks making progress on their climate commitments, but rather proof that they’re not moving fast enough in the climate emergency. It’s time for the federal government to step in, they say.

Stand.earth climate finance director Richard Brooks told Canada’s National Observer the lack of meaningful change in board composition reflects the lack of significant change in how banks invest. He said that banks have been given years to adapt their boards for the era of climate change and have failed to do so.

That shortcoming comes into particular focus for RBC, which was the only bank to increase its fossil fuel-linked directors, Brooks said. According to the recently published Banking on Climate Chaos report, RBC is Canada’s largest funder of fossil fuel companies, having recorded approximately $348 billion worth of loans and investments since 2016.

In April at its annual general meeting, RBC added Barry Perry to its board of directors. Perry previously served as the CEO of Fortis, and now sits on the board of Capital Power. In early May, Capital Power abandoned its $2.4-billion carbon capture project at its Genesee power plant in Alberta.

“This was supposed to be the premier project in Canada that was to showcase the viability of [carbon capture and storage], and the company itself admitted it is not financially viable,” Brooks said. He added that with billions of dollars flowing into various carbon capture projects across the country, it begs the question of why renewable energy projects are struggling to secure the level of investment they need.

“I kind of wonder at the senior level if we have a conflict of interest where you've got a couple board directors who are connected very closely with the fossil fuel industry who have influence … in terms of how they make decisions at the bank,” he said.

“This is not an issue that's just come up in the last six months,” he added. “The incremental steps, if they're taking any, are not sufficient in terms of reducing their footprint and their contribution to the [climate] problem. This is why we need regulation.”

Some of the regulations currently being contemplated by Ottawa relate to what’s called disclosure and a taxonomy. Disclosure refers to a requirement for Canadian banks to transparently report on their emissions from their financing, while the taxonomy refers to forthcoming guidelines to determine what counts as sustainable investing.

Neither disclosure nor taxonomy would actually restrict how banks do business. At a recent Senate banking committee hearing to discuss Independent Sen. Rosa Galvez’s proposed Climate Aligned Finance Act (CAFA), chair of Brookfield Asset Management and head of transition investing Mark Carney called both pieces important for the financial sector.

However, other proposals in CAFA would require banks to set more money in reserve when they lend to fossil fuel companies to act as shock absorbers to the bank through the energy transition, due to the expected increase in risk of fossil fuel investments as the energy transition unfolds.

Carney said this capital allocation proposal is achievable, but he would not recommend it.

Brooks says Carney is wrong, and voluntary action won’t work. Brooks explained that as Canada and the world transitions its economy off fossil fuels, new fossil fuel infrastructure becomes more financially risky. If banks don’t set aside more money to account for that risk, “we could face a crisis like the housing bubble in 2008 and previous bubbles that have burst when there's been a lack of funds to backstop any sudden decrease in value.”

“I think we need to treat oil and gas like big tobacco,” he said. “They need to be regulated into action, and those who are propping up the industry and facilitating its growth and the harm that it causes need to be regulated as well.”

At a recent senate banking committee meeting, Brussels-based Finance Watch chief economist Thierry Philipponnat called it imperative that Canada start seriously tackling fossil fuel risks to the financial sector.

“If we don’t, it’s certain that, in human terms, we’ll have a new financial crisis on top of the climate crisis,” he said. “Exposure to fossil fuels is equivalent to the amount of subprime mortgages that triggered the crisis 12 or 14 years ago.

“The same amounts and the same causes will produce the same effects.”

Environmental Defence senior climate finance program manager Julie Segal told Canada’s National Observer that board directors who serve both fossil fuel companies and the banks raise questions about whose interest they serve.

“Despite many years of discussion and self-celebration, we have not seen sufficient action toward shifting money away from harmful activities into sustainable investing,” she said. “So we need new policy rules, like the Climate Aligned Finance Act, for example, to ensure these financial institutions are doing what's needed.”

One reason bank executives may not want rules governing their capital allocations is because directors are paid through a combination of salaries and performance-based incentives if certain financial targets are met. Segal explained that if a bank faces higher capital requirements, it would mean a lower return on equity. Return on equity is a common financial metric that is central to directors’ performance-based compensation.

So setting aside more money for risky fossil fuel investments may be in the bank’s best long-term interest, but “might not be appealing to an executive whose payment is defined based on that ratio,” she said.

The Climate Aligned Finance Act, if it were to ever become law, would restrict directors from joining bank boards if they are linked to a fossil fuel company, whether it be sitting on its board or having lobbied in the last five years for an organization that is not climate aligned. Moreover, it would also require some types of companies to appoint an individual with climate expertise on their board.

Speaking at a sustainable finance panel last week, Galvez described bank financing ratios as $3.9 to fossil fuels for every $1 invested in renewables, when the best available guidelines recommend an entirely flipped ratio of $4 for renewables for every $1 to oil and gas. She said one reason for this is because of who sits on the boards.

“If you're wearing multiple hats and you're [making] these decisions about where to invest, this poses not only an appearance, but actually a potential, and almost real, conflict of interest,” she said.

“The chances of having that orderly transition [off fossil fuels] is going away because we are waiting too long,” she said.

“We don't want them to have all their eggs in the same basket and increase exposure [to the oil and gas sector] because of all the physical risks, transition risks, reputation risks, [and] litigation risks that are exponentially increasing.”

At the same time Galvez is attempting to push CAFA through the Senate in the hope it can be brought before the House of Commons, the House environment committee is studying the financial sector’s impact on climate change.

Bank CEOs were invited to testify, but declined.

“That tells me that they don’t want to be in the spotlight and they fear the regulation that is coming down the pipeline,” said Brooks.

Segal called the House study important because it’s the first time the federal government is formally studying how finance is affecting climate change, unlike previous studies aimed at attracting sustainable investment or the risks of climate change to the financial sector.

“People are being harmed by climate change that's directly tied to the decisions these banks and the CEOs who run them are making, so they need to be able to explain the impacts their investments are having to the government, and to Canadians,” Segal said.

Comments

Excellent article, reassuring to see action at the very top thanks to Rosa Galvez from the Senate, Mr. Brooks from Stand.earth and Ms. Levin from Environmental Defence with their objective analysis that makes good use of the cautionary and highly relevant examples of the financial crisis of 2008 AND what happened to big tobacco.

Mark Carney is starting to look like the wrong guy to be leading the much vaunted "transition" that is obviously just more greenwashing, more sucking and blowing. As Ms. Galvez points out, the word has lost traction because it's now officially TAKING TOO LONG, an understatement.

The numbers of 4 to 1 STILL being spent on maintaining the status quo of big oil versus renewables tells the tale in the context of the "bottom line," which is any bank's mantra after all.