Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This story was originally published by Grist and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

For the past year and a half, you may have heard a lot about butter. It started with a viral video of influencer chef Justine Doiron carefully slathering two sticks of butter directly onto a wooden cheese board, seasoning the thick layer with flaky sea salt and lemon zest, arranging torn herbs and red onion across the surface, and finally finishing the dish with flower petals and a drizzle of honey. This was the butter board, a TikTok trend that quickly reached escape velocity and was featured by The New York Times, CNN and Today.

On high-end restaurant menus, the once-humble bread-and-butter course snowballed into $38 table-side “butter service” and 14-inch cylinders of creamy, imported carved-to-order butter earned prominent placement in restaurants’ open kitchens. By early March, New York Magazine could declare that “butter has become the main character.”

What accounts for butter’s spectacular renaissance in American cuisine? According to the U.S. dairy industry, it’s their own public relations campaign that started the spread. The industry marketing group Dairy Management Inc. has claimed credit for the butter board in industry press, because it paid Doiron as a sponsor at the time of her video. While Doiron’s original butter board video did not include an advertising disclosure — and, according to Dairy Management, was not itself technically part of the partnership — the chef posted a Dairy Management ad two days before her viral post and was part of the industry group’s “Dairy Dream Team” of paid influencers at the time. (Doiron did not respond to an interview request, but Dairy Management told Grist that her contract has since expired.)

Dairy Management, whose funding largely consists of legally mandated fees collected from farmers, is one of a constellation of government-supported dairy marketing groups that also includes the Fluid Milk Board, a beverage-focused entity whose promotion arm has paid Emily Ratajkowski, Kelly Ripa, Amanda Gorman and more than 200 others to promote milk on social media. (The milk board also recently sponsored a section in New York Magazine’s The Cut, focused on women in sports.) In recent years, Dairy Management has partnered with mega-influencer MrBeast at least twice, filming him as he toured a dairy farm and paying him to promote a dairy-focused competition in the video game Minecraft.

In perhaps dairy promoters’ biggest coup of last year, the limited-run McDonald’s Grimace shake went viral after TikTok users began crafting miniature horror films featuring the bright purple beverage. Dairy Management has a longstanding partnership with McDonald’s; beginning in 2009, it placed two dairy scientists at the fast food chain to help incorporate more dairy into the menu. Less than a decade later, 4 in 5 McDonald’s menu items contained dairy, according to a Dairy Management board member. Dairy Management has even funded research to help improve McDonald’s notoriously glitchy milkshake machines.

“My hope is that farmers, when they see a new milkshake or a new McFlurry at McDonald’s, that they know that it’s their new product,” Dairy Management CEO Barb O’Brien said on a podcast in December.

A spokesperson for McDonald’s told Grist that they could not independently confirm the proportion of their offerings that contain dairy due to variations in local menus, but added that the fast food chain makes its own menu decisions. “Our partnership with [Dairy Management] helps McDonald’s ensure the quality and great taste of the dairy-based items on our menu, and deepen relationships with the thousands of dairy farmers who supply milk, cream, butter and cheese to restaurants across the U.S.,” the company said in an emailed statement.

Partnering with food companies to roll out products that contain ever-escalating quantities of dairy is one of the industry group’s tried-and-true strategies. In the last couple of years, Dairy Management has partnered with Taco Bell to launch a frozen drink mixing dairy with Mountain Dew and a burrito with ten times the cheese of a typical taco. The organization also assisted with last year’s rollout of pepperoni-stuffed cheesy bread at Domino’s and supported marketing efforts for General Mills’ Oui line of yogurt.

Thirty years after the era-defining “Got Milk?” campaign — itself a project of the California Milk Processor Board — the U.S. dairy industry’s PR machine appears to be getting a second wind. The point of all these efforts is straightforward: the dairy promotion boards’ mission is to increase demand for their products. They spend hundreds of millions of dollars, collected from farmers and milk processors, on annual research and advertising in hopes of growing the market for dairy domestically and abroad.

However, as dairy consumption and production continue to grow, so too does the industry’s environmental footprint. In 2019, the EPA estimated that U.S. dairy cattle emitted 1,729,000 tons of methane each year, pollution roughly equivalent to 11.5 million gasoline-powered cars being driven over the same period. A United Nations report found that the dairy sector’s global greenhouse gas emissions rose by 18 percent between 2005 and 2015.

Meanwhile, it’s not entirely clear that all these efforts are helping the average dairy farmer. The number of U.S. dairy farms has fallen by three quarters in the last 30 years, as farmers’ costs rise and milk prices fluctuate. Many small and mid-sized dairy farms have been driven out of business and farmers’ net returns fall below zero year after year. In 2000, farms with more than 2,000 cattle produced less than 10 per cent of milk, but by 2016 farms of this size were responsible for more than 30 per cent of U.S. production. The diverging trend lines have prompted some farmers to question whether the focus on market growth above all else — which has been accompanied by increasing climate pollution and the collapse of small dairy herds — is still the best policy.

Ever since Congress passed the Dairy Act in the 1980s, farmers have been required to pay 15 cents per hundred-weight of milk (equivalent to a little less than 12 gallons) toward industry promotion programs overseen by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Ten cents is sent to local promotion entities and the remaining five cents go to the national Dairy Board, which promotes all dairy products. Farmer contributions to the national program totaled $124.5 million in 2021.

The Dairy Board in turn sends money to Dairy Management Inc. Milk processors work under a similar structure, paying their own assessments to the Fluid Milk Board, which works exclusively on promoting a category that includes milk, flavored milk, buttermilk and eggnog. The Fluid Milk Board received $82.4 million in processor fees in 2021. Its marketing arm is called MilkPEP.

In an emailed statement, a Dairy Management spokesperson told Grist “all dairy research, promotion content and information not only complies with all regulations and standards, but also seeks to help consumers make informed decisions about the foods they choose for themselves and their families, including nutritious, sustainably produced dairy.”

The financial structure of these efforts is complicated, but the end result is that these programs, which are known to farmers as “checkoffs,” bring in more than $200 million each year for the dairy industry alone. As a result, the industry takes care to note its accomplishments. For instance, in the first eight years of the checkoff partnered with Domino’s Pizza, the average store increased its cheese use by 43 per cent.

Other promotional efforts, however, have amounted to slickly-produced flops. Last year, the Fluid Milk Board hired actor Aubrey Plaza to hawk “wood milk” in an apparent effort to lampoon plant-based milk alternatives, which resulted in a formal complaint filed by a group of physicians who advocate for plant-based diets. Another effort involved a Board-funded website featuring Queen Latifah, which was devoted to combating the seemingly fictional phenomenon of “milk shaming.”

Some recent industry-funded persuasion campaigns have been more subtle. In 2021, the fluid milk checkoff sponsored a wellness weekend for top editors from Bustle, New York Magazine, Marie Claire and others at a $750-per-night Hamptons resort where they participated in workouts led by a celebrity trainer and “partook in milk-forward meals.” Congressional disclosures indicate that the Fluid Milk Board held USDA-approved advertising and marketing contracts with Vice Media and Food52 in 2021. A spokesperson for MilkPEP told Grist that these were branded editorial contracts to develop milk-inclusive recipe content.

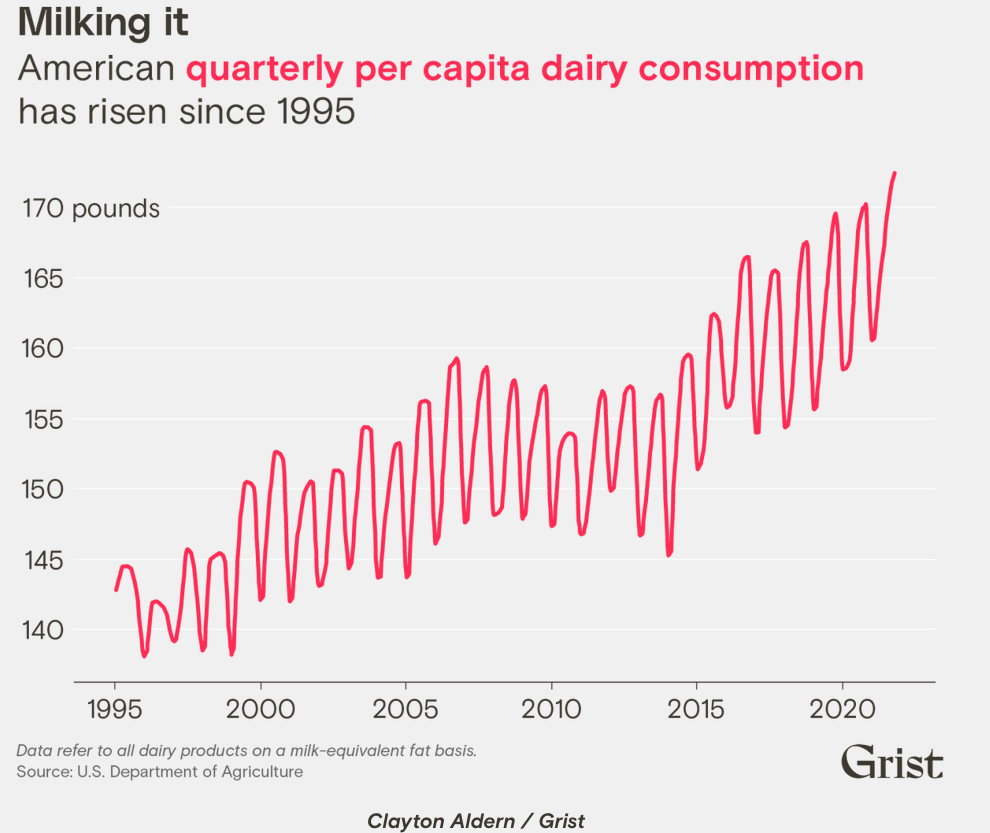

There’s some evidence that all this marketing has worked. A recent USDA report delivered to Congress claimed that farmers earn $1.91 for every dollar spent on “demand-enhancing activities” for fluid milk, $3.27 for every dollar spent promoting cheese and $24.11 for every dollar spent boosting butter. An independent evaluation by the Government Accountability Office in 2017 likewise found that, between 1995 and 2012, the fluid milk program returned $2.14 for every dollar spent.

After decades of growth, per-capita U.S. dairy consumption reached an all-time high in 2021, though fluid milk consumption has been steadily declining since the 1970s. This presents formidable challenges for climate action: meat and dairy consumption are responsible for a full 75 per cent of the country’s diet-related greenhouse gas emissions, even though animal products account for only 18 per cent of calories consumed.

And even setting aside climate concerns, small-scale farmers worry that this emphasis on demand growth might actually end up edging them out of the market. They say that the checkoffs have unfairly benefitted a few big producers, supercharging their growth while driving others out of the industry.

“[The checkoff is] set up to be entirely demand-side,” said Wisconsin farmer and former Dairy Board member Rose Lloyd. “You’re not allowed to talk about price, you’re not allowed to talk about supply. It’s a wasted effort.”

Lloyd and her family maintain a herd of 350 cows, and while checkoff assessments represent less than 1 per cent of her revenue, she says she feels like she’s paying to reinforce a structure that’s working against her farm and her community. For example, she has watched a neighbouring dairy farm quadruple in size to supply mozzarella to a nearby factory that produces frozen pizzas. The local infrastructure has struggled to contend with the waste produced by all those additional cows.

“We have massive water quality issues,” she told Grist. “It’s a real crisis right now on all the legs of sustainability: ecologically, socially, economically.”

Some farm groups are holding out hope that they can persuade Congress to pass a form of supply-management legislation that limits total milk production, which they are pitching as a win-win for small-scale farmers and the environment. If the government placed a cap on the amount of dairy produced in the United States, the idea goes, such a policy could theoretically ensure that a market exists for all the dairy produced.

A similar model has functioned in Canada for decades. Each year, annual dairy demand is forecast based on the previous year’s sales figures. The resulting estimate is divided among provincial boards, which in turn distribute production quotas to individual farmers. In exchange for promising not to market more milk than the quotas allow, farmers are guaranteed minimum prices for their products — meaning they’re somewhat insulated from the seasonal price fluctuations and rising costs that plague their U.S. counterparts.

To maintain this delicate balance, Canada prevents an influx of cheap imported milk using high tariffs. In part for this reason, the system is not without controversy. Critics argue that the policy pushes up dairy prices and the quota licensing system can make it hard for new producers to enter the market.

Still, the system has enough admirers that some are hoping it will be adopted in the U.S. Earlier this year, representatives from the National Family Farmers Coalition, or NFFC, flew to Washington, D.C., to try to persuade legislators to adopt supply-management legislation through their proposed “Milk from Family Dairies Act” in the next Farm Bill. The bill would establish price minimums and quota-like “production bases” for farmers. Farmers would have to pay additional fees to export their product and the policy would raise import fees where possible.

Antonio Tovar, senior policy associate at NFFC, said the proposal has garnered support from environmental groups who see supply management as a means of reducing emissions from feed and trucking.

Nevertheless, Tovar is clear-eyed about the bill’s likelihood of passage, at least in the near term. “I have to be honest with you, I’m a little bit pessimistic about these proposals being included in the next Farm Bill,” he said, citing Congressional gridlock and limited political will to pursue the change.

In the meantime, the dairy checkoff has set its sights on the export market. Specifically, it’s promoting pizza — which one executive called “a strong carrier for U.S. cheese” — in the Middle East and Asia. In Japan, the checkoff and Domino’s launched a “New Yorker” pizza topped with a full kilogram of cheese and served with a packet of seaweed and maple syrup. The product was subsequently rolled out in Taiwan.

Domestically, there are still some fast-food menu items that haven’t yet been topped with a slice of American cheese or shaken with milk. In a 2022 blog post, Dairy Management Inc. chair Marilyn Hershey pointed out that 80 per cent of the two billion chicken sandwiches sold in the U.S. each year do not contain a slice of cheese.

The checkoff, she wrote, was engaging with Chick-fil-A, Raising Cane’s and McDonald’s to change that.

Comments

If you think Canadian Supply Management pushes up prices, I disagree. My 4 litres of 2 % is less expensive in Canada than equivalent in USA on average. And our 4 litres is a bit larger than an American gallon. Many other dairy products when changing weight into metric and US $ to Cdn $ are less. Cheese is exception. I only buy Cdn cheese on sale as it keeps for over 6 months. See USDA monthly dairy stats