Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The federal government will assess the toxicity of a harmful compound in oilsands tailings after the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and environmental groups requested a review.

Naphthenic acids (NAs) accumulate in oilsands tailing ponds — which currently hold at least 1.4 trillion litres of wastewater — and have been found to harm fish and amphibians; there are still research gaps on how it affects human health. Large tailings leaks from Imperial Oil’s Kearl tar sands facility spurred renewed calls for health studies, regulations and environmental reform.

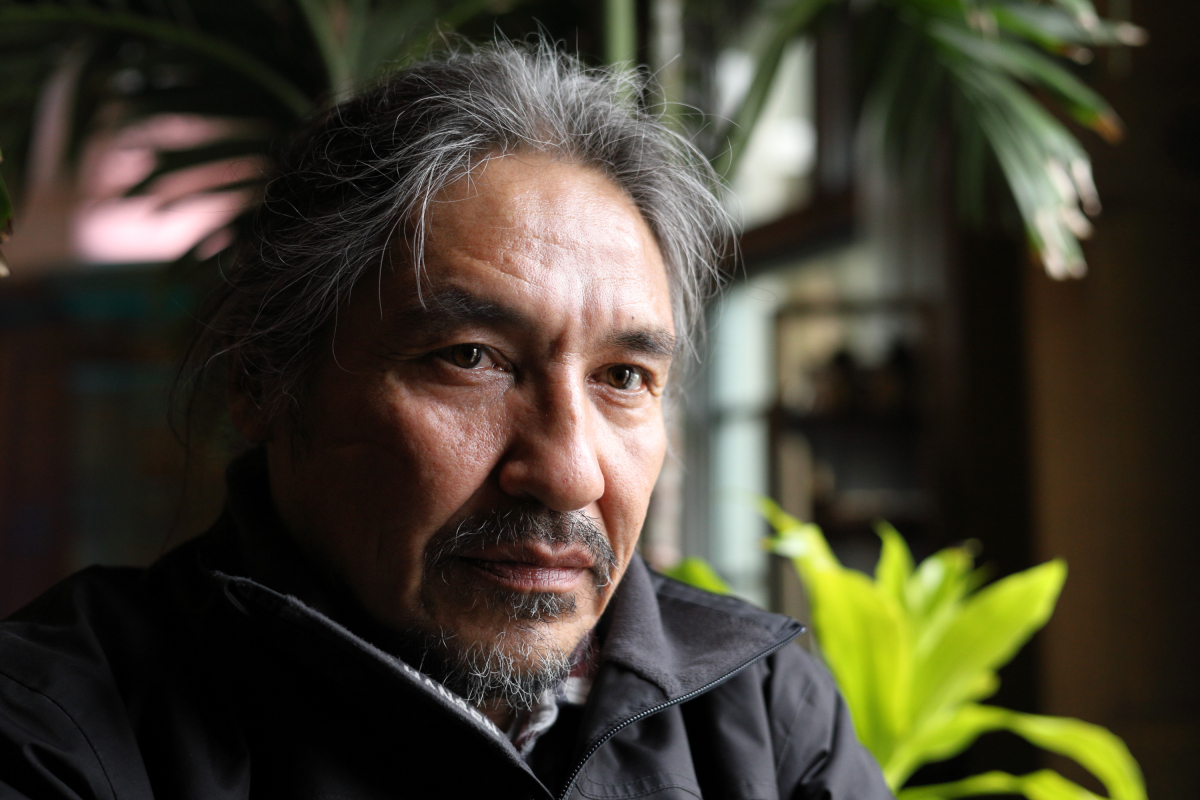

“The cancerous effects of naphthenic acids have long been known to scientists, industry, governments and sadly to our community of Fort Chipewyan,” said ACFN Chief Allan Adam in a release on May 30. “Fort Chipewyan is the closest downstream community from Alberta’s Tar Sands and it is no surprise that we live with the highest cancer rates in the Province, over twice that of the rest of Alberta.”

A group of nearly 40 leading toxicologists, scientists and health experts also submitted a letter supporting the need to prioritize NAs for risk assessment on May 27.

The existing data suggests that naphthenic acids from oilsands processed water may pose a “considerable threat to the environment and human health, including acute and chronic toxicity to aquatic life and potential disruption of endocrine functions and other impacts on reproductive health in humans,” the experts wrote.

ACFN’s request was fulfilled on May 28, when federal environment Minister Steven Guilbeault and Health Minister Mark Holland said they are adding naphthenic acids to the list of substances to be assessed for their toxicity under Canada’s flagship environmental law: the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA).

Adam is grateful Guilbeault and Holland answered their call to investigate naphthenic acids, calling it “a great step forward.”

If naphthenic acids from tar sands are determined to be toxic, the government will be required to take risk management measures, including potentially regulating or restricting these substances, according to Ecojustice.

“It's really good news, although it's a small piece of the puzzle,” said Aliénor Rougeot, climate and energy program manager at Environmental Defence.

“The tools that this would potentially unlock are really important.”

Currently, the federal government can level charges under the Fisheries Act when harmful substances enter fish-bearing waters. There is an ongoing investigation into the Kearl incident on those grounds.

However, if naphthenic acids are deemed toxic, the federal government could use more proactive tools to regulate the substance, such as requesting emergency preparedness plans for the companies, limiting how much is released or possibly asking for specific money to be put aside for cleanup, said Rougeot.

Rougeot noted that listing plastics as toxic under CEPA allowed the federal government to institute the single-use plastics ban (which is currently before the courts). However, “there's a lot of substances that are found to be toxic and they just do some monitoring and reporting requirements for industry to follow,” so environmental groups will keep pushing for the federal government to use the full extent of its powers, she said.

This type of citizens request for assessments of substances was made possible by changes to CEPA.

The decision to investigate naphthenic acids has symbolic importance too, Rougeot explained. This is finally a recognition that the threat posed by this substance — which is not bound by any federal guidelines, science or investigation — is real and should be investigated, said Rougeot.

“That's really important, to stop denying that communities are basically nearby or potentially contaminated by something that's really dangerous and is now being investigated by the federal government,” she said.

The news comes just days after Guilbeault announced a two-year extension of an emergency interim directive ordering the petrochemical industry in southern Ontario to clean up its act in response to dangerously high benzene levels at Aamjiwnaang First Nation.

Vast quantities of oilsands tailings have long been perched in man-made ponds along the Athabasca River. But dangers arising from the ponds were reinforced early last year when it was discovered tailings had seeped from Imperial Oil’s Kearl site in northern Alberta for nine months. Apart from one email, downstream communities were not notified. It took a massive spill of 5.3 million litres on Feb. 4, 2023 for the long-term seepage — which Imperial Oil first noticed in May 2022 — to be made public through an environmental protection order, sparking outrage from Indigenous communities, the public and politicians.

In March, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation filed a lawsuit against the Alberta Energy Regulator for the regulator’s failure to notify the nation about two large leaks of toxic tailings from Imperial Oil’s Kearl site in northern Alberta.

For more than two decades, experts and front-line communities near and downstream of the oilsands have called for studies on the cumulative health impacts of oilsands tailings. An initial proposal was submitted to the federal government in 2019, but has not been fulfilled.

Guilbeault’s letter says that the assessment of naphthenic acids and other substances on the list would begin in June 2025, a year after the government intends to publish the full list of substances for consultation.

Environmental groups will be pushing to get the naphthenic acid assessment underway sooner than that, said Rougeot.

— With files from Matteo Cimellaro

Natasha Bulowski / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments