Thank you for helping us meet our fundraising goal!

Climate change figured prominently in the controversy swirling around Bill C-59, the wide-ranging federal law that took effect as Parliament adjourned for its summer recess. Part of the new law amends the Competition Act’s deceptive marketing provisions to address corporate “greenwashing.”

Greenwashing occurs when companies make “unsupported environmental claims.” Thanks to Bill C-59, corporate claims about the good their businesses do for the climate may now be reviewed. Competition Bureau Canada will be able to fine companies for deceptive marketing if they don’t offer “adequate and proper substantiation” for claims about their environmental benefits.

But what about governments? Do they greenwash, too? Bill C-59’s logic should apply in even stronger terms to Ottawa and the provinces. In ideal democracies, governments should offer their constituents accurate, verifiable information about their policies and actions.

When it comes to climate change, Canadian emissions records don’t necessarily support government claims of progress. Climate change debates in this country need governments to live up to the principle Ottawa now expects of the petroleum industry.

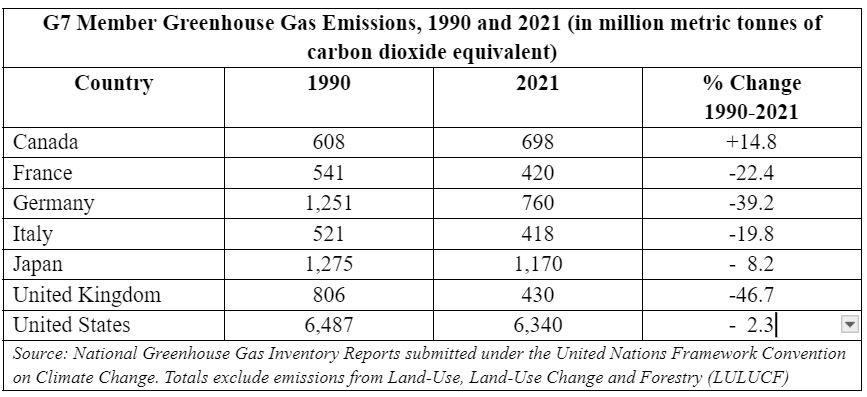

The country’s national emissions record clearly shows Canada is a climate action laggard among western democracies. For example, Canada is the only G7 member where recent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions levels are higher than they were in the early 1990s.

In 2021, Canada’s GHG emissions were 14.8 per cent higher than they were when the international community prepared to meet in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit. Canada’s trajectory since Rio is literally a world apart from the European members of the G7. Even the United States, now the world’s largest oil producer, was able to report lower total emissions in 2021 relative to 1990.

If this record surprises you, it may be because governments prefer to tell a different story. In this alternative narrative, our political leaders are the champions of climate change progress.

Alberta, arguably, is Canada’s best example of a government greenwasher. Since 1995, Alberta partnered with Ottawa to promote building one of the world’s largest oil factories in the oil sands of northeast Alberta. In the past generation, we have witnessed the unfolding of what Canada’s national energy regulator labeled perceptively as “an era of unprecedented growth” in the oil sands. Explosive oil sands production growth propelled the country into the top tier of global oil producers — of which Canada is the world’s fourth largest.

Exponential growth in oil sands production propelled the country’s GHG emissions total skyward. According to Annex 10 in Canada’s latest greenhouse gas inventory report, oil sands emissions in 1990 were 16 million tonnes (Mt) per year. In 2022, those emissions were a record 87 Mt; they grew spectacularly over that period, by more than 440 per cent.

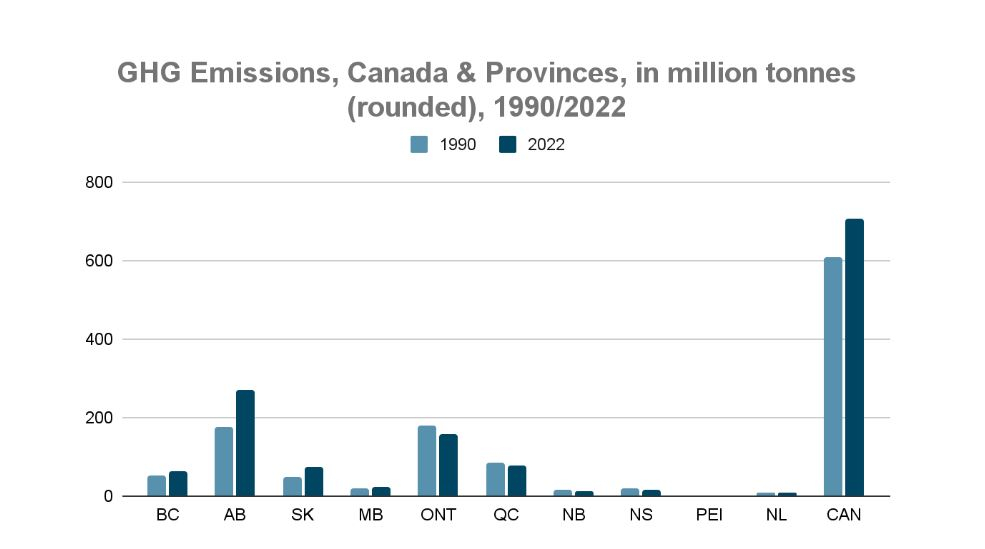

In 2022, Canadian GHG emissions were 100 Mt higher than in 1990. Literally all of that increase may be accounted for by a 92.7 Mt increase in Alberta’s emissions over that period. Most of the Alberta increase comes courtesy of aggressive oil sands exploitation.

The record is stark. Canada, thanks largely to Alberta, emits millions and millions more tonnes of greenhouse gases now than was the case when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was signed in 1992.

But governments, especially that of Alberta, market exactly the opposite picture.

Like its clients in the petroleum industry, Alberta howled in protest when Bill C-59 became law. Ever a good patron, Premier Danielle Smith rushed to defend petroleum producers. In a blistering, hyperbole-laced attack on Ottawa, she portrayed Alberta as “a global leader” in reducing emissions. C-59 would irreparably damage the public’s ability to hear the truth about “Alberta’s successes in reducing global emissions.”

Rebecca Schulz, Alberta’s Environment Minister, devotedly sells this same story. When Canada’s last national inventory report was released in May, Schulz said Alberta’s “total emissions went down.”

Minister Schulz was correct only in the most trivial sense. Alberta’s 2022 GHG emissions were 1.1 Mt lower, less than one half of one per cent lower, than they were in 2021. A more accurate portrayal of this “success” would present it in the context of the spectacular increase in petroleum emissions noted above. Then trivial success becomes clear failure.

Even in Schulz’s imagined world, it seems misleading to say that “(e)missions are declining in oil and gas.” Oil sands emissions in 2022 had never been higher. Those GHG-intensive barrels constitute a whopping 83.3 per cent of Alberta’s oil production.

Under Bill C-59, if a company made these claims, they might be guilty of deceptive marketing. But nothing stops pro-fossil fuel governments from trying to market a very similar picture.

Greenwashing also describes ambitious corporate climate promises that lack evidence of GHG emissions reductions in the near term. This is true of some governments' promises to reach net-zero by 2050.

Alberta has followed this script with respect to its promise to reach net-zero by 2050. But Alberta doesn’t have any emission reduction targets between today and 2050. None.

The federal government, too, may be tempted to greenwash. After nurturing oil sands growth in the 1990s, Ottawa now seems prepared to try to reduce emissions in the sector. A proposed cap and trade system will be this tool.

But, due to compliance flexibilities and exclusions, the proposed cap would deliver only modest emissions reductions from 2019 levels. Most importantly, petroleum emissions still would be tens of millions of tonnes higher than when Canada and the global community promised to tackle climate change in 1992.

Do these facts offer the “adequate and proper substantiation” needed for Ministers Steven Guilbeault and Jonathan Wilkinson to tell Canadians that the federal cap was “ambitious”? Well-respected research groups such as the Institute for Sustainable Development concluded Ottawa overstated what the policy would deliver. If overstatement and exaggeration are hallmarks of greenwashing, then perhaps Ottawa, too, should be more careful in how it describes its actions.

It’s difficult to refute the view that political communication today, more than in any previous era, is rife with propaganda — and when it comes to climate change, propaganda is easier than action. To prevent this from happening, we must convince our political leaders that deceptive language about climate change, intentional or not, will cost them politically. The first steps on that path are to inform electors of the real, unvarnished facts. Electors must be encouraged to hold their politicians accountable for policies that may harm future generations.

Ian Urquhart is a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Alberta. His teaching and research there focused on the political economy of natural resource exploitation and climate change. His 2018 book Costly Fix: Power, Politics, and Nature in the Tar Sands was short-listed for the Canadian Political Science Association’s Donald V. Smiley prize.

Comments

I agree, the government should be held just as accountable to bill C-59 as the companies. It no secret that the government greenwashes the numbers to make them selves look good, than tell Canadians the real truth. They should be highlighting the provinces like Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario for contributing the most to our disgraceful numbers, because conservative premiers are in the back pockets of the oil & gas industry. Soon we will have Pierre "Snake oil Salesman" Poilievre becoming PM and will further disgrace this country as he rolls back environmental and climate change initiatives. I wouldn't be surprised to see him roll back C-59 as well.

Justin Trudeau is no saint either when it comes to climate change. He talks-the-talk, but doesn't have the backbone to do what is needed to bring in line our failure to clean up our act.

Fraudulent misrepresentation in Canada. Criminal Code 361 (1). A false pretence is a representation of a matter of fact, either present or past, made by words or otherwise, that is known by the person who makes it to be false and that is made with a fraudulent intent to induce the person to whom it is made to act on it. To determine whether fraudulent misrepresentation occurred, the court will look for six factors: A representation was made. The representation was false. That when made, the defendant knew that the representation was false or that the defendant made the statement recklessly without knowledge of its truth.

I'll show you fraudulent representation. Canada has one of the worst forestry industries in the world. The forest fires in this country are a result of intentional forest degradation and climate change.

A huge percentage of the forests in this country are plantation monocultures vulnerable to disease insects and fire.

And this will only get worse over time.

Because these practices are deliberatel the emissions from fires and bad management practices should be counted in the National Inventory because they are not accidents or acts of God.

It's a pairing of the worst of govt and worst of the natural resources sector.

https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2020-09-13/150-million-dead-t…

I'll show you fraudulent representation. Canada has one of the worst forestry industries in the world. The forest fires in this country are a result of intentional forest degradation and climate change.

A huge percentage of the forests in this country are plantation monocultures vulnerable to disease insects and fire.

And this will only get worse over time.

Because these practices are deliberatel the emissions from fires and bad management practices should be counted in the National Inventory because they are not accidents or acts of God.

It's a pairing of the worst of govt and worst of the natural resources sector.

https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2020-09-13/150-million-dead-t…

https://youtu.be/n5UlUx79LXU?si=cTvRvaL5cflg3tHG

https://youtu.be/BPhc_rtonTw?si=zzl3xQIE3nO-li7x

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/08/us/park-fire-california.html

Wow they really have no idea how stupid they are in using fire suppression and letting dry fuel build up.

I always mention Germany. Every part of that forest gets visited every 15 to 20 years to harvest mature trees and clean up dead trees.

They don't have problems with fires.

When and how did the fire start?

The fire ignited on July 24 near Chico, a college town in Butte County, north of Sacramento. After igniting, the fire exploded to more than 120,000 acres by the next day and then nearly doubled in size the night after that. Officials said the cause of the fire was arson.

Somebody should be hung for this kind of unbelievable stupidity.

People dying in the equivalent of WW2 fire bombs not because of climate change but because of stupid practices starting from when they plant 10 to 20 times more than capable in natural forests because of moisture availability causing extreme risk of drought.

The Park Fire is burning primarily in dry, thick timber with heavy dead and down fuels. Low relative humidity contributed to significant fire behavior today, including slope-aligned runs and frequent spotting

https://inciweb.wildfire.gov/incident-publication/calnf-park-fire/wedne….