Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The Canadian government has cut back on an important measure that detects critically endangered North Atlantic right whales and triggers protective measures.

Right whales are found and logged through visual confirmation from flights or ships and through acoustic detection from gliders. However, a policy recommendation document prepared for Minister of Transport Pablo Rodriguez says that Canada has slashed its flight hours for right whale detection by at least 50 per cent in 2024.

Hours will be cut from “from 350 hours down to between 150 to 175 hours, aligned with Budget 2023 funding levels,” reads the document, which was obtained by Canada’s National Observer through an access-to-information request. Rodriguez approved the measures in March 2024.

Today there are fewer North Atlantic right whales than there are days in a year, after centuries of intensive whaling and a temporary recovery that peaked around 2010. Two main causes of right whale deaths are ship strikes and entanglements in fishing gear, and Canada has management measures in place to reduce fatalities. For example, if a right whale is detected, a fishery closure of 15 days is triggered for crab and lobster, which can be extended if another whale is detected again in the same area.

The species is a hot topic – biologists stress that every death of a right whale matters, since numbers are so minuscule. The animals have been listed as endangered since 2005 under the Canadian Species at Risk Act. Numbers have steadily decreased since 2011, when the population was at around 481. Now, there are approximately 356 right whales, and none have died in Canadian waters since 2019.

Right whales' struggle predates entanglement and ship strike issues. For thousands of years, Miꞌkmaq in the area used the whales for food and other things — the oil for heat, the bones for tools. But in the 1500s, fishers from abroad travelled across the Atlantic and overfished the whales almost to extinction. A fishing ban was put in place in 1935, but the whales have been recovering at a slow rate.

Canada’s National Observer reached out to Transport Canada for clarification on the reduction of flight hours and did not receive any response until two weeks after our deadline. The ministry’s initial response did not confirm the cut back in flying hours. Nearly a full week later, the ministry still did not provide a clear answer, but instead noted that “aerial surveillance efforts are aligned with Budget 2023 renewal.”

The ministry said it is “currently funding projects to enhance surveillance capabilities,” including securing a third underwater glider. It also highlighted thermal imaging cameras that are currently being tested, and a new partnership that uses drones to detect the whales.

“The flight hours and trajectories have been refocused to optimize operations and enhance the efficiency of Transport Canada’s resources. Should an increase in flight times be needed and feasible, the amount can be adjusted,” reads the ministry’s response, which emphasized that “surveillance flights are only one of the monitoring tools used to monitor whale movements, this is why Transport Canada is increasing its acoustic surveillance capacity, including securing a third underwater acoustic glider.”

Losing that amount of flight hours is significant, explained Sean Brilliant, senior conservation biologist for marine programs at the Canadian Wildlife Federation, and represents a “potential threat.”

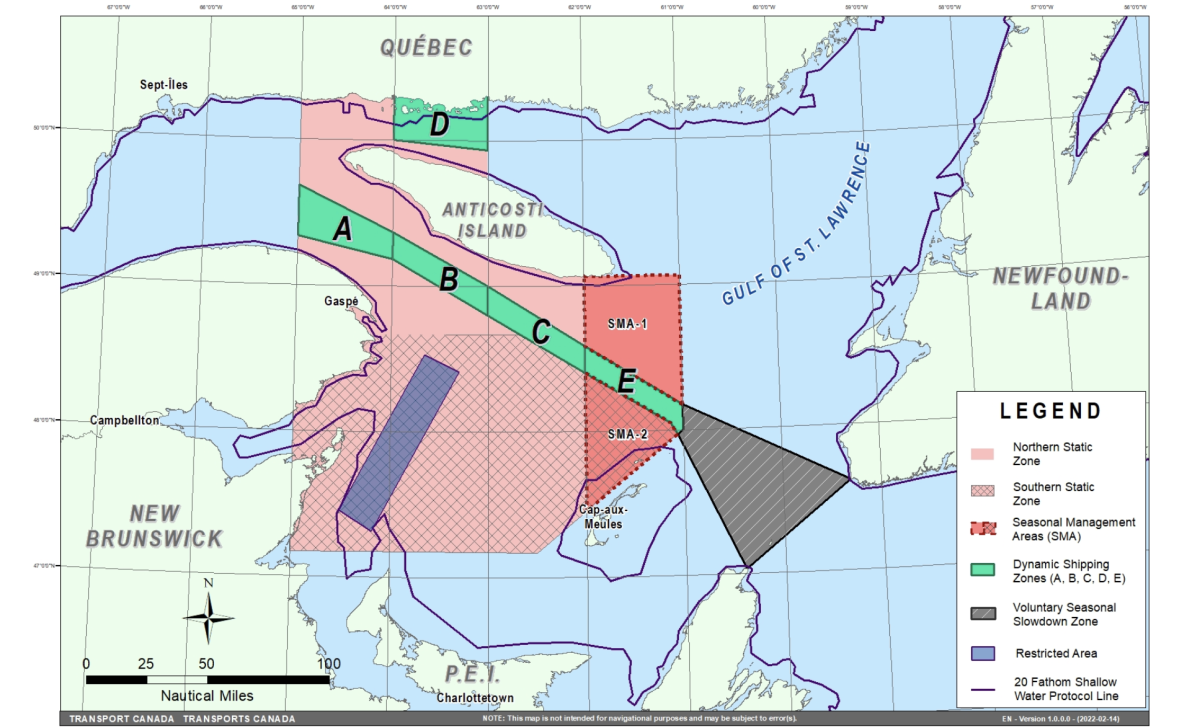

In Canada, entanglement falls under the Department of Fishery and Ocean’s (DFO) jurisdiction, and vessel strikes are the responsibility of Transport Canada (TC) to negate. Every year, the two ministries work together on mitigation measures that are enacted between April and November when the whales are most active in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. To reduce vessel strikes, the government has both mandatory and voluntary slowdown measures for ships. For example, there is a mandatory 10-knot speed restriction in two seasonal management areas, which are located south of Anticosti Island and west of Newfoundland.

Some slowdowns, however, are usually only brought into effect when whales have been spotted — or when there are no flights to confirm there aren’t whales present.

The policy recommendation document said slashing the flight hours “could lead to increased precautionary vessel slowdowns and impact industry.”

The policy document notes that “a voluntary slowdown in Cabot Strait began in 2020 and has been generally successful, although increased industry participation would improve protection efforts.” The strait is located between the tips of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, and is shown in grey in the map below. The ministry confirmed that the average participation rate in the voluntary areas has been about 76 per cent, which it described as “high participation.”

Voluntary measures don’t cut it, Brilliant explained, because there is incomplete compliance from the shipping industry, as expressed in the document. And even if ships are complying and slowing down to 10-knots, that doesn’t mean there is no risk to whales.

“We can't say, there, we've slowed all the ships down to 10 knots, clap the dust off our hands and walk away,” he said. “No — at best, we're solving 10 to 15 per cent of the problem, and we need to remove far more of the risk than 10 to 15 per cent if we want to give this animal a chance.”

He says reducing flights comes in tandem with the Canadian Space Agency ending its program, which aimed to detect the whales from space using satellites.

If TC was serious about protecting right whales, it would implement mandatory slowdowns instead of voluntary ones, said Susanna Fuller, vice president of marine non-profit Oceans North.

She added that while she acknowledges aerial surveillance is expensive, important data can be gleaned from images taken from above. When a whale is spotted entangled in fishing gear, for example, researchers can tell exactly which individual it is. Right whales are recognizable by the patterns of callosities — patches of tissues that serve as habitat for little white crustaceans.

She says the drop in surveillance will hurt the collection of this data over time, which helps monitor changes and patterns.

“Your data is only as good as your year-over-year, when you fly the same transect and you detect the same things,” she said.

New and innovative tools are needed to track the whales because they are “really hard to find,” Brilliant said. The creatures spend up to 80 per cent of their time underwater (which makes gliders useful tools because they detect whales using sonar), and less than 200 of them come into the Gulf of St. Lawrence each year. He stresses that flights are just one way to detect the whales, but are a proven measure and need to be part of a more robust approach to protect the dwindling species.

Comments

If flights are so expensive why are we not using drones equipped with cameras and whatever electronic equipment needed for surveillance/communication/monitoring etc.

I admit to scanning the report so I may have missed reference to drones.

It really ticks me off when the technology available is not put to use appropriately

Every commercial vessel should be required to fly drones ahead of their path when not out in deep sea. That's not a very expensive requirement any more.