Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Record heat is fueling an accelerating megafire crisis in California. The ongoing massive Park fire is the latest monster to burn off the old-climate charts.

Before 2018, the state's largest wildfire on record was the Thomas fire, which burned 280,000 acres. At the time, the Thomas fire felt apocalyptic. The current Park fire burned more in just its first three days. It's currently the state's fourth-largest on record, at 430,000 acres -- joining the rapidly swelling ranks of unprecedented megafires.

Beyond California, forests all over the world are also getting baked by record-breaking heat. As everyone knows by now, the primary driver of this global heating is pollution from burning fossil fuels -- oil, gas and coal. Extreme heat events are turning forests into kindling. Californians, like people in many other parts of the world, are at the sharp end of this stick.

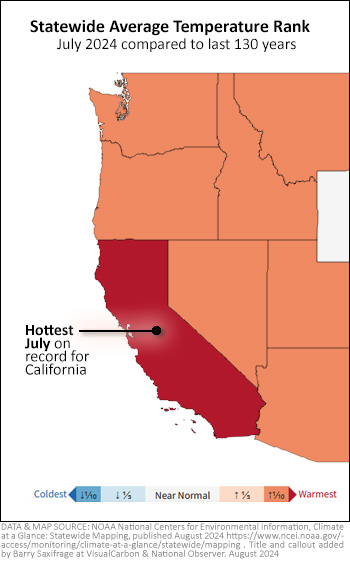

Hottest July on record

This year California suffered through its hottest July on record. That's according to NOAA data stretching back 130 years.

By the end of that record-hot month, the forests were baked and ready to burn.

The Park fire started on Wednesday, July 24. Less than two hours after it sparked, it was listed at 40 acres in the state's first incident report. An hour after that, the first evacuation orders went out. Less than 24 hours later, it had exploded to over 70,000 acres. The next day, it hit 165,000 acres. And on Saturday, just 72 hours after it started, the Park fire had burned 350,000 acres.

As noted above, that already exceeded any California wildfire on the books before 2018.

At the peak of the Park fire, more than 6,500 firefighters were fighting it -- using 525 fire engines, 190 bulldozers, 180 water tenders, 45 helicopters, and a fleet of airplanes dropping water and fire retardant.

The cost and effort needed to attack these hotter-climate monster fires is daunting. California boasts the world's fifth-largest economy and will be able to pay for such Herculean efforts longer than most other parts of the world.

But, as the next chart shows, even California, with all its resources, is already losing the battle.

California's exploding megafire crisis

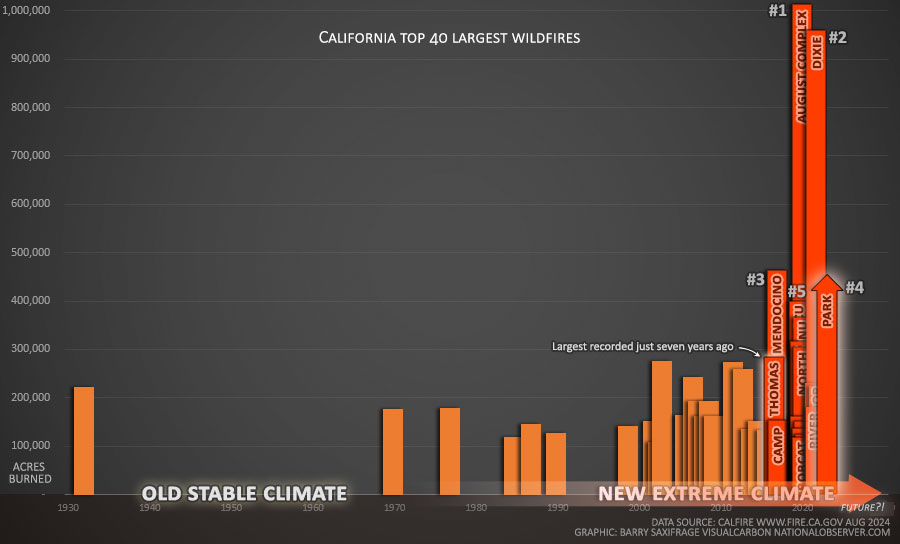

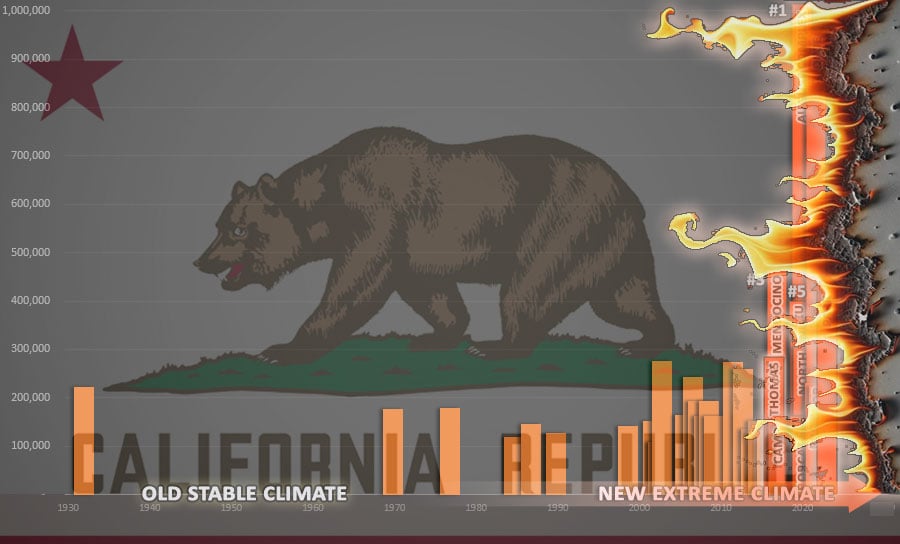

To illustrate the stunning acceleration of the state's wildfire crisis, I created the chart below. It shows California's 40 largest wildfires, arranged by the year they burned. The height of each bar shows how many acres each fire burned.

As you can see on the left side of the chart, when we all lived under the blessings of a stable, lower-energy climate, Californians rarely had to deal with megafires. And when they did, the biggest fires topped out at around 200,000 acres.

Now, billions of tonnes of fossil fuel pollution later, we live under the shadow of an increasingly destabilized and higher-energy climate. And California megafires have responded with rising frequency and fury.

First came a dramatic surge in the frequency of big fires. You can see this on the chart with the pile up of orange bars starting in the new millennium. Gone are the peaceful decades, like the ones I grew up in, with only one or two big fires.

Next came a dramatic surge in the size of the biggest fires. You can see this on the chart by the towering cluster of red bars starting with 2017. During the century before that, the ceiling for extreme wildfires was below 300,000 acres. But in just the last seven years, eight monster fires have shot past that old ceiling. And the biggest wildfires now reach a million acres.

This explosive surge in both the number and size of California megafires is happening despite all the increased resources and technology the state has been able to throw at them.

Before we leave that chart, take a look back at it and consider which decade you would pick to live in: Would you pick the current decade crammed with million-acre, town-eating megafires and smoke-choked summers? I sure wouldn't.

But I also know that fire weather will continue to grow ever more dangerous until we stop fueling it with more fossil fuel pollution. So, as bad as it is today, it can quickly become much more dangerous.

The megafires that are coming

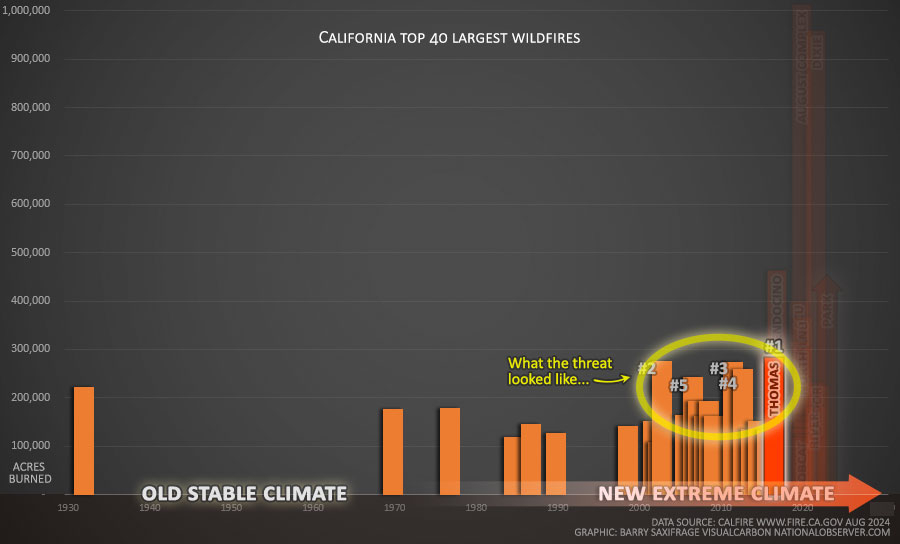

It can be hard to imagine a significantly different future. As a result, humans often underestimate the rapid changes we are cooking up with our climate pollution.

California's wildfire crisis provides a good example. Let's step back a few years to the end of 2017. Here's what California's wildfire crisis looked like back then.

That year, the Thomas Fire exploded to become the state's largest fire on record at 282,000 acres. It's shown by a bright red bar on the right of the chart. Firefighters, politicians, and the public were shocked by the size and fury of this record-breaking fire. At the time, the five largest wildfires on record had all burned in that current decade. They are numbered on the chart.

Back then, it was common to hear warnings that this was the "new normal" for fire in California. That phrase incorrectly assumed that the current climate and fire regime would continue on into the future.

We now know that the actual threat was explosively larger. That supposed "new normal" didn't even last until the end of the year.

What will the next decade bring?

What we do know is that the more fossil fuels we burn, the more extreme our future fire weather will become.

Hotter climate spawns more megafires

Climate science has documented many ways in which fossil-fuelled global heating turbocharges wildfires around the world. And California wildfires are an excellent window into that science because the state has been so well studied.

For example, one recent study funded by NOAA found that "climate change is to blame for record-breaking California wildfires." It concluded that "nearly all the observed increase in burned areas over the past half-century is due to human-caused climate change."

Another study, led by researchers from McGill University, showed that "hot-dry extremes" are the conditions that breed explosive, hard to contain megafires. And the study documents how these hot-dry conditions are becoming increasingly common and more extreme in western parts of the United States due to climate change.

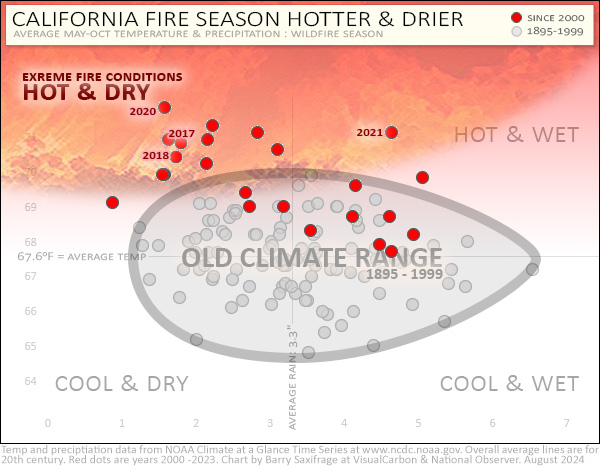

To illustrate California's trend towards more extreme heat and dryness, I created the chart below using NOAA data.

On this chart there is one dot for each year since 1895. These dots show California's average temperature and precipitation during its traditional wildfire season of May to October.

The gray dots are years before 2000. A gray oval marks the range under the old climate.

The red dots are the years since 2000. Notice that all these years have been hotter than the "old normal". And, critically, many were hotter than any year was before 2000. Heat combined with drought brings the most extreme fire weather. And if you look in the upper left corner of the chart, you can see California's hot-and-dry years are growing far more extreme.

I've labeled four of the five most extreme wildfire years on the chart — 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2021. The current year, 2024, isn’t on it yet because there are months still to burn in this fire season. But as we saw at the top, July 2024 is already in the record books as the hottest ever in California.

Trees can't move. California forests have been forced to survive as best they can as our fossil fuel burning has turned up the heat and cut off their water.

This link between a warming climate and increased wildfires is an ancient one in California, according to yet another study. This study found that "climate has been the dominant controller of wildfire activity in the Sierra Nevada region in the past 1,400 years." Researchers from Brown University studying ash layers in old lake sediments determined that warm and dry conditions were linked to increased wildfire as far back in time as the layers went.

There will always be sparks to start fires in California, from both nature (lightning) and humans. For example, in 2018, the largest California fire at the time was started by a common spark thrown off when a rancher hammered a metal stake into the ground. But to turn a normally harmless spark into a city-eating megafire requires a lot of kindling-dry fuel (forests, brush, grassland) that is primed to burn explosively fast. And that's exactly what our new extreme hot-dry conditions are serving up.

How extreme the fire weather will become in California and around the world depends on how much more fossil fuel pollution we choose to emit. Rising temperatures are the most certain result of continued fossil fuel burning. As an International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report highlights: "Every tonne of CO₂ emissions adds to global warming."

And once emitted, damage is locked in. As the World Meteorological Organization warns: “the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere is irreversible on human timescales and will affect climate for millennia.”

As California's wildfire crisis highlights, the abject failure of today's adults to rein in their fossil fuel emissions is locking our kids, and generations to come into a dystopian future.

-------------------------------------

ENDNOTES

Here are a few related items that readers may be interested in:

- OFFSETS BURNING -- The Park fire burned 43,000 acres of forest that were set aside for carbon offsets under California’s carbon offset program. You can read more about this event on Politico. This is just the latest carbon offset forest to go up in flames. This highlights the growing climate risk from trying to greenlight additional fossil fuel CO2 emissions by claiming that this CO2 will be safely locked away in trees or other nature-based carbon storage.

- WESTERN FORESTS -- A recent study of forests in the American West from 2005 to 2019 found that carbon storage is declining. The reason is a one-two punch of climate changes (ex: hotter temperatures and droughts) and the rising wildfires that come with it. They warn that carbon losses could accelerate dramatically in coming years. Here's one of the articles that covered this study: Forest carbon storage has declined across much of the Western U.S., likely due to drought and fire

- GLOBAL FORESTS -- Another recent study found that the record-breaking heat globally in 2023 caused a dramatic decline in the amount of CO2 removed from the atmosphere by the global land "sink" (forests and the rest of the biosphere on land). This study found that land regions exposed to extreme heat in 2023 turned into CO2 sources that year -- emitting a combined 1.73 billion tonnes of CO2. Here's one of the articles that covered this study: Plants absorbing less carbon dioxide in 2023, accelerating global warming

- RECOMMENDED BOOKS -- If you are looking for an in-depth read about how climate change, wildfire and forestry practices are impacting Western forests -- particularly the great pine forests stretching from Mexico through Canada -- I recommend Daniel Mathews' book: Trees in Trouble. And, of course, if you haven't already read John Valliant's multi-award-winning tour de force, Fire Weather, the Making of the Beast, it deserves a spot on your reading list.

Comments

Another brilliantly illustrated essay. Thank you Barry.

One can imagine the ramifications of an icrease in the flow of First World climate refugees to the US Pacific Northwest and to BC. However, many ex-Californians are moving back to their family roots in the Midwest, New England and other cooler Atlantic states.

One can also imagine the ramifications for our imported winter produce grown in California and Mexico. When the heat rises, the water supplies go down.

What I've been wondering is, how big are these fires (in California and also in BC) compared to the total amount of forests available to burn? Will we at some point run out, because ALL the forests will have burned down? Or is this still very small compared to the total size of burnable areas?

I believe the record 15 million hectares burned in Canada last year was 1/24th of the approximately 367 million hectares of forest in Canada. That's pretty staggering. The issue you raise is a real one, though I think if Canada doesn't get successive "off the charts" burns, the rate might be low enough for substantial regrowth.