Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

There was some polite applause after retired atmospheric scientist John Reid stood up to ask his question.

Reid, who used to work at Environment and Climate Change Canada, wanted to know whether the public actually had the tools to track the government's climate change promises, when it takes years for the department to release greenhouse gas emissions data.

“How do you hold people accountable when you have such a delay in the information becoming available?” he asked. “And is it credible, when it comes from the same organization that produces the regulations?”

Reid was in the audience at a panel discussion on climate change science at an Ottawa convention centre on Tuesday. The event was hosted by Statistics Canada, the country's national statistical agency.

The Trudeau government has promised to set a national price that polluters would pay for releasing heat-trapping carbon emissions into the atmosphere. This carbon tax would be a major component of the government's plan to slash greenhouse gas emissions. Federal officials have been drafting regulations to implement the new tax.

John Moffet, a top Environment and Climate Change Canada official who is acting as associate assistant deputy minister, responded to the scientist by saying that he hopes the new rules to implement the carbon tax will also usher in a new era of transparency.

“The short answer is that both issues will improve in the near-term," Moffet told Reid. “I think you will see more timely information, and more credible information."

It just isn't clear when that will happen.

Critics, including staff from the office of the auditor general, say the public is often left in the dark about government commitments to tackle climate change, with little public data available to hold politicians to account for their promises. Successive federal governments have promised to take action on climate change and reduce emissions since the 1990s, but none of them have ever met their goals.

The auditor general's office has also spent a lot of time trying to pin down the government on its progress, warning that Canada has a long way to go to meet its goals.

Moffet, from Environment and Climate Change Canada, explained that the government can tackle these concerns through new emerging regulations.

“As the reach of our regulations is extended, in particular through broad-based initiatives like carbon pricing and the clean fuel standard, we will also be able to extend the reach of our [carbon pollution] reporting obligations,” Moffet told Reid at the event.

Earlier in the talk, during introductory remarks, Moffet also said Environment Canada is now “the most active regulator in the federal government” in terms of the number of regulations it puts into effect.

The federal Environment Department in Canada publishes greenhouse gas emissions data on a yearly basis — which is then delayed by several months before being publicly released. For example, the most current national inventory report on emissions includes data up to the year 2015.

The department gets its emissions data from across the country through both “a very general reporting obligation that’s been in place for about a decade,” and through more specific regulations, Moffet said. Then the department makes sure the data has been assembled, collected and reported as required, which he said takes time.

The exchange between Moffet and Reid coincided with the release of a new United Nations report that found an "alarming gap" between commitments made by countries to reduce greenhouse gases and the amount of action required to prevent global warming of more than two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, considered to be a threshold of major irreversible damage to the economy and the planet's ecosystems.

Data sought to compare profitability, emissions

Andrew Leach, an associate professor at the Alberta School of Business at the University of Alberta, who was the chair of the provincial government’s climate change advisory panel in 2015, agreed that the complexity of gathering emissions inventory data means that it takes time to coordinate existing data into a single national profile.

“It is a challenge to get it out there. It’s not like it’s there and it’s being held on to for 15 months,” he said.

But Leach also suggested in his own remarks that Canada needs more detailed and timely data on carbon pollution so it can better design policies and programs to mitigate climate change.

He said data was lacking that cross references revenues and profitability with emissions intensity, energy use and capital stock. Economists need this complete picture to better predict the impact of climate change policies on regions and industries, he said.

An example he gave is figuring out whether the stock of low-efficiency furnaces is concentrated in low-income housing. Such data could help governments craft better retrofit policies, building codes or incentive programs, he said.

Monica Gattinger, professor and director of the Institute for Science, Society and Policy at the University of Ottawa, said the need for more data in the context of the low-carbon economy transition was "exceptional" given the scale of the issue.

"I think we really need to do a better job of thinking through ideally what [these needs] are, and in the context of limited resources, what can we all begin to build on," she said.

Beyond data, Gattinger also pointed to the need for a political "decision-making framework" that would help local communities and groups get more involved with their own low-carbon transitions, which she said her institute had seen a significant “appetite” for at the municipal level.

Statistics agency looking to publish more green data

After the panel discussion, Greg Peterson, director general for agriculture, energy, environment and transportation at Statistics Canada, said in an interview that the federal statistical agency is making its own changes to provide more data.

In addition to the agency’s environmental statistics program that produces the Canadian System of Environmental-Economic Accounts, which processes GDP (economic growth) numbers to figure out how much energy use, for example, is embedded in commodity numbers, the agency has recently been pushing “the development of additional products,” said Peterson.

For the past year or so, the agency has been examining how to calculate the impact of clean technology, which Peterson noted doesn’t fall neatly into pre-existing industrial or technological categories.

To that end, the agency has been “tweaking” its survey of environmental goods and services, he said, to “identify and target clean technologies” and another survey to measure the use of those goods.

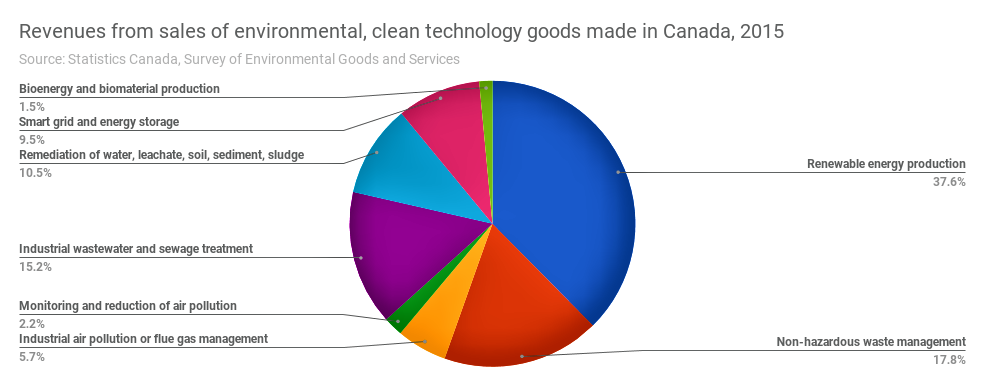

In 2015, Canadian firms sold over $3.4 billion "environmental and clean technology goods" manufactured domestically, and related services sales accounted for almost $3.8 billion, Statistics Canada reported Oct. 30.

Ultimately the goal is to produce an environmental account, said Peterson, that can reveal the contribution that clean technology makes to the existing national accounting framework.

He said the agency was also in the "very early stages" of figuring out how to collect data on the secondary effects of what a low-carbon economy will do to society: things like the health of the labour market, the health of Canadians, whether the proper skill sets are being developed, and what people's attitudes are as the economy transitions.

"This is the range of things that we want to try and take a look at it," he said.

Comments

Well we’ll see how that goes, won’t we? Another plan, not a bad one, but right now, it is just words, not Action.

I understand that ‘things take time’ but I find it interesting that reforming the NEB (as promised in 2015) PRIOR to pipeline approvals was preempted by the approval of Kinder Morgan in BC, Line 10 in Ontario, and other Fossil Fuel infrastructure PRIOR to reforming the NEB. Backwards isn’t it?

And how is it that the promised implementation of UNDRIP is continually preempted by the Federal Government challenging lawsuits of Indigenous Nations on approvals that do not comply with Free Prior and Informed Consent?

Nowhere in the Federal Government’s “plans” for combatting Climate Change and meeting our Paris commitments is there anything about reducing fossil fuel extraction. In fact the emissions targets for Tar Sands extraction are higher than the current levels of extraction. And each of the proposed and approved pipelines come close to tripling pipeline capacity, thus greatly expanding Oilsands’ extraction.

The mantra of “getting our resources to tidewater” is rather pointless given the Chinese Ambassador’s recognition that the “Canadian Oil Sands is not competitive .... [and disbelief] that Chinese enterprises would still be interested in this”.

None of these actions lines up with the stated ‘plans’ of the Trudeau government to address climate issues. They’re talking the talk ......

Some excellent points. You are underlining what has been occluded in these experts' search for better data. I suspect we wouldn't be so anal about our statistics, if we were more focused on the task ahead of us. Reducing carbon dioxide in the air, won't happen by wasting years making sure we're measuring 'effects' correctly, while working hard on the ground to dig up more expensive carbon.

But as Canadians of liberal incination, we're used to eating our cake and having it too.

Official John Moffet promises us "more credible information"?

Hmmm...information is either credible. - or not.

I think keeping records are a good thing...but no substitute for action on the ground. Take just one example from this article...the question of low efficiency furnaces and whether they are being used in low income housing projects.

Here's an activists take: 1. If the houses are being built by capitalist developers, most likely the furnaces are as cheap as money can buy.

2. Low income housing is the least of our worries; what's being done to make our mega mansions being readied for the global elite looking to 'a clean, free country' to move to....net 0? Because if you're wealthy, for sure net 0 should be demanded of those McMansions.

3. If the low income housing is being built by government, or approved by government, we don't need to wait for data to know what we should do. High efficiency furnaces should be the law. NO exceptions.

Governments are playing the rhetorical game, while continuing to pander to the old business as usual crowd....Sure...in time, good data will show that. But why wait for proof when we could move on sustainable regulation now?

Studies, commissions, even cross country town halls are generally delay tactics. Let's continue to have them, but have some actions in progress to report. We've left global warming very late....time for everyone to begin implementation..............and keep records of that, as we go.

Here is a link to the Clean Fuel Standard Discussion Paper Submissions including one directly to ours.

Clean Fuel Standard Discussion Paper - Ammonia (NH3) as a Carbon-Free Fuel

University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Prof. Dr. Ibrahim Dincer, Yusuf Bicer

Hydrofuel Inc., Greg Vezina (Chairman and CEO), Frank Raso

http://nh3fuel.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=48&Itemid=…

66 comment submissions on the Clean Fuel Standard Discussion Paper:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B0uMvHfE8C2uQXdFNjdoSHRzWDQ