Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

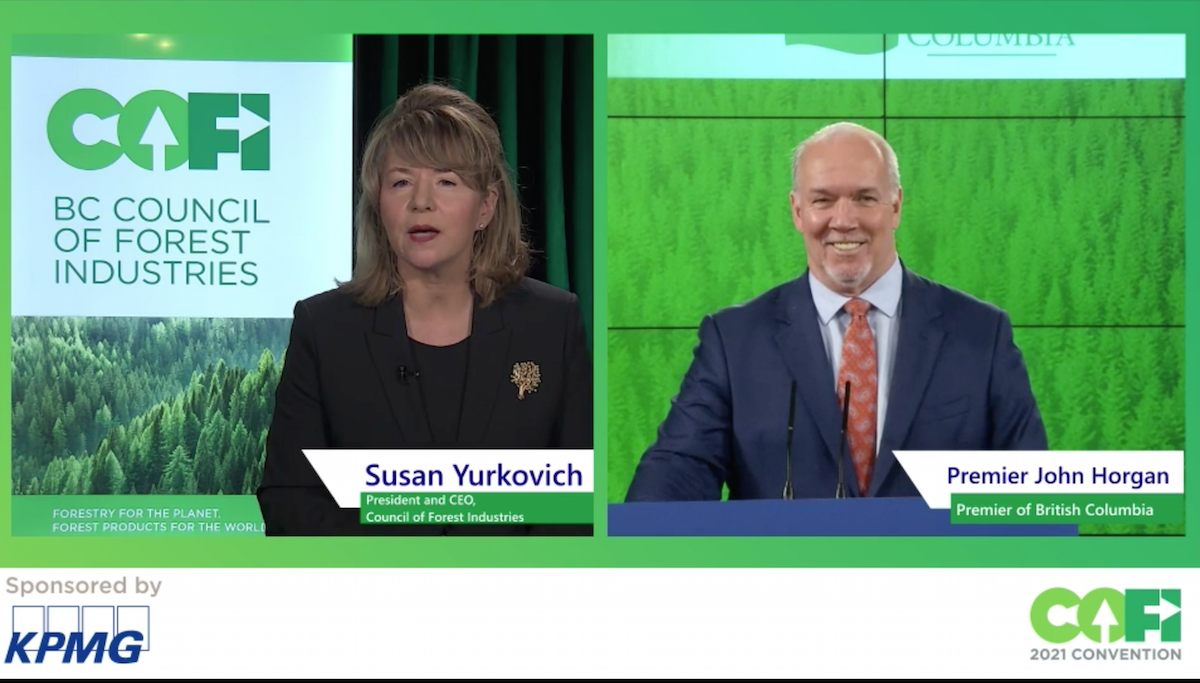

Though the battle to protect ancient trees is brewing in his own backyard, B.C. Premier John Horgan did not utter the word old-growth when talking to logging industry leaders Thursday.

Horgan — keynote speaker at the Council of Forest Industries conference — did not highlight what steps the province is taking on its promise to meet recommendations from the strategic old-growth review, which calls for a radical shift from timber extraction to protection of at-risk ecosystems.

Meanwhile, increasing numbers of people, frustrated by the rate at which the province is protecting old-growth, are heading to the Fairy Creek blockades near Port Renfrew in Horgan’s Vancouver Island riding.

Demonstrators at roadblocks to various entry points to Teal-Jones' Tree Farm Licence (TFL) 46 were served an injunction on Tuesday, although the RCMP had not arrived as of Friday morning.

However, Horgan said Forests Minister Katrine Conroy had a mandate to modernize forestry, and she’d issue an intentions paper in the weeks ahead.

“Our vision for the forest industry is very clear. It's going to be diverse, it's going to be competitive, and it's going to be sustainable,” said Horgan.

“One that places people first, and one that works directly with Indigenous peoples.”

Industry better share timber tenure or government will

The shrinking supply of timber from the pine beetle infestation and forest fires is an undeniable challenge with too many people chasing too few trees, Horgan said.

The premier expressed disappointment on the lack of progress by large companies holding most of B.C.’s forestry tenure in reaching deals with First Nations and smaller communities, so they could access timber to create value-added products and add jobs.

He sent a salvo over the bow of the sector, warning his government would step in to make it happen.

“There’s no magical solution to the lack of fibre,” Hogan said, adding work can be done to encourage companies and Indigenous nations to reach agreements.

“And those who do have tenure, and do not want to share it, well, we'll have to step in and ensure that there is fair compensation,” he said.

Horgan reiterated the province’s pursuit of value over volume, citing Wednesday’s announcement of a $4.2-million investment to develop mass timber for the construction sector, and the establishment of an advisory council to help facilitate that goal.

“An essential part of our approach to the industry is to make sure that we do focus on that value-added marketplace, and we stop chasing every stick to get it out as quickly as we can,” Horgan said.

He cautioned industry to put money away now with the “staggering” prices for lumber for rainy days associated with a cyclical sector.

“We all need to make sure that we're taking advantage of these extraordinarily high prices,” Horgan said.

“So, when the market starts to stabilize again, we're not looking back to government or out to workers to make concessions to make sure that the companies can continue to be profitable.”

Environmental groups pushing the province to act on the old-growth strategic review said Horgan’s desire to ensure small communities and First Nations are involved in forestry is positive.

But it does not address the problem that only three per cent of the remaining old-growth forests in the province support massive, ancient trees.

“Right now, all it sounds like is a new way of dividing the pie for logging without acknowledging it’s becoming smaller and smaller,” said Jens Wieting of Sierra Club BC.

“Action must be tied to acknowledging that we have an ecological crisis and what old-growth remains is so important for our survival from a climate risk perspective.”

The all-time high prices for lumber paired with the looming expectation in the industry that government will increase old-growth protections mean companies are motivated to log big trees as fast as they can, Wieting said.

“As the province continues to talk and log, companies will try to get as many big trees as possible,” he said.

“So we really have to find those mechanisms — now — to preserve what’s left.”

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments

It is sad the even the NDP cannot protect what is left of the amazing environment we were blessed with in this country and especially in BC.

Social Democracy, like the Liberals and the Conservatives are in the hands of Neo-liberalism and getting their hands on everything everywhere. Everything is commodified to extinction no matter what.

Horgan, just like our Rachel Notley in Alberta are nothing but soft Liberals without much of a real understanding of true social democracy.

The extraction sector - as its name suggests, is intent on stripping the earth of its natural wealth - with neither the intention of restoring what is taken, nor of remedying the ghastly waste and destruction it leaves behind - almost without exception, with total impunity

The apogee of the Anthropocene is probably already behind us. At humanity's growth rate and consumption rate, we have most likely passed the tipping point and a viable earth ecosystem is no longer possible.

The extraction sector certainly seems to have recognized and accepted this proposition and are with increasing desperation, striving to wring the last remaining vestiges of wealth they can identify from the earth's mantle. What they will do with that useless wealth when the viability of life on the earth collapses is anyone's guess. They certainly embody the futility of human evolution. And in the process have turned the science of Geology into a soulless and venal slave to mammon.

Unless timber is on private land not rolled into a Tree Farm Licence (TFL) or other Ministry-standard management, logging companies cannot ‘grab as many trees as possible’ while the government ‘dithers.’ That is, there’s a limit to the allowable cut (AAC) on Crown land or private land officially designated in a Managed Forest Unit (MFU) which is managed to Ministry standards like allowable annual cut, regeneration, &c. in order the owner enjoys a considerable property tax discount.

Companies can, of course, maximize the tolerance allowed in TFLs and MFUs: plus/minus 50% of AAC in any given year, but +/- 10% over the whole five-year planning period. Fines and/or commensurate deduction of Crown land chart—or even licence— result when the 5-year target is missed.

A considerable proportion of the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Land Grant is private forest land which is not included with a TFL (rolling in private with Crown forest managed to Ministry standards is often a condition of granting a TFL), nor officially designated an MFU (entirely private forest managed to Ministry standards in order to enjoy a property tax discount). The government has little control over such land, much of which has been or will be converted to non-forestry uses (like residential, recreational or industrial real estate which does not enjoy the MFU tax shelter). Most of this private land was logged before WW II; a huge tract was burned from north of Campbell River down nearly to Courtenay a few years after the War. Many of these private forest holders have elected to liquidate the mature second-growth over that last two decades. There is no Crown-imposed AAC on wholly private land not in a TFL or MFU.

Old growth preservationists seem to focus on Vancouver Island, the southern half of which includes the huge E&N Land Grant area—virtually the whole east coast of the Island from Sayward to Sooke. It seems to me a notable number of stats about remaining old growth in BC are calculated from this, the most heavily logged Coastal forest—that is, not including the vast Mainland Coast rainforest. This common type of statistical abuse is intended, I think, to make the amount of remaining old growth look smaller than it really is in order to raise alarm amongst the mostly uninformed urban residents of densely populated southwest BC. For example, to claim that only 2% of OG remains in the province, one would have to subtract OG protected in parks and ecological reserves (about 12% of the province) and low-volume, high elevation or low-elevation coastal bog forests which preservationists often do not consider OG simply because it isn’t the iconic, gigantic kind of OG on better sites. Failing to mention these statistical assumptions is misleading and, IMHO, doesn’t help preservation activism when it is revealed.

The government abuses stats, as well—or, perhaps better described as taking advantage of general ignorance of forests and forest polices. For example, when politicians say “sustainable,” it doesn’t mean preservation of OG for its own sake. Crown policy is, generally, to liquidate OG— which is not growing (and is often decadent, volume being lost to decay) —and replace it with relatively fast-growing younger stands. I think many people imagine “sustainable forest management” means sustaining OG such that it will never run out, as if several centuries is a cut-control horizon. Perhaps it could be, but that’s not the policy nor what is meant.

In fact, what will be sustained is not even the amount of timber per area that was found-wealth as virgin forest. Rather, the much lower, but faster accumulating yield of 60–120 years growth is what will be sustained after the much bigger virgin volume has been “liquidated.” The difference is called the “fall-down effect.” (It is theoretically possible to sustainably harvest OG: it would require rotation periods of several centuries and would net much less volume per area per time-period.)

Unfortunately, most of the low-elevation forests on southern Vancouver Island were logged many decades before AAC standards were regulated, the liquidation mandate was enacted, and the concept of sustainable commercial harvest was developed and enforced. That’s why there’s so little OG left in this region. On the other hand, there is a substantial amount of Coast Western Hemlock OG remaining today on north Vancouver Island and the Mainland Coast.

The NDP’s Forest Practices Code of the 90s ended unsustainable overcutting previously prevalent, AACs were substantially reduced (averaging about 25% provincewide, but in some Timber Supply Areas, up to 75%), parks and protected areas almost doubled to 12% recommended by the UN, logging waste billed and/or punished in other ways, while major treaty negotiations with First Nations were advanced or completed (Haisla/West Fraser Mills and the Nisga’a Treaty, for examples).

In spite of all that, the remaining tidbits of OG on southern Vancouver Island were bound to become more controversial, even as licensees forwent chart on places like Meares Island, Nitnat Triangle and Carmanah, to name a few, past, “War in the Woods” battlegrounds. It seems reasonable to preserve the last of the last. Would that it were that simple.

As to Fairy Creek: I too would like to see this area preserved because it truly is one of the last, intact, whole-drainages of OG in the region. However, the logging company owns the right to log it. That means, if the government intends to preserve it, it would have to expropriate and pay the company for the lost timber value and opportunity. A little thought reveals that the Crown is reluctant to creat this kind of precedent. That said, I wish the protestors luck.