The Alberta government pulled off a bit of a feat with its new climate plan, managing to disappoint even those who were fully prepared to be disappointed.

Danielle Smith’s government even sounded like it had disappointed itself. "We're behind,” said Sonya Savage, the provincial minister who pulled the short straw and was tasked with presenting the document. “I wish this plan had been out two years ago. We know we have work to do."

Savage won’t be doing that work herself — she is not running for re-election in Alberta’s upcoming vote. And her boss was atypically absent from the unveiling. Premier Smith did make a statement, demanding the feds “stay in their lane” and “stop setting unrealistic, unachievable targets.”

Despite her absence, Smith may have issued the most concise summary of the Alberta emissions reduction and energy development plan: “Instead of moving away from hydrocarbons, we will use these resources in innovative ways.”

The first thing to know is that Alberta’s plan is not really a plan in any normal sense of that word. Andrew Leach called it “a plan to make a plan.” The University of Alberta economics professor is being generous. There are nods towards advisory groups and committees. There is apparently a whole lot of research to be done. But no benchmarks, regulations or laws, no commitments to reduce emissions. The closest is a promise to “explore” an emissions limit for the oilsands. One that “aligns” with targets set by the big oilsands companies themselves through their Pathways Alliance.

There is some vague hand-waving about a carbon-neutral economy by 2050. The Alberta government even resurrected that old Harper era throwback, “aspirational.” You might have dared hope the days of aspirational targets were over but, no, Alberta now has an “aspiration” to achieve net-zero by mid-century.

The Smith government is keen on carbon capture and apparently even more hyped on hydrogen (104 mentions, almost two per page of the document). But strangely reticent about renewables for a province that leads the country in wind and solar (solar makes a meagre 17 appearances). And when renewables do make an appearance, the UCP government couldn’t resist taking swipes — the world’s leading energy analysts (not to mention the thousands of Earth scientists contributing to the IPCC) will be shocked to learn that the sun sets every day and the wind blows intermittently.

Why bother releasing this not-a-plan at all? The obvious answer is there’s a provincial election looming at the end of May. Someone must have realized that swing voters expect the government to have a climate plan.

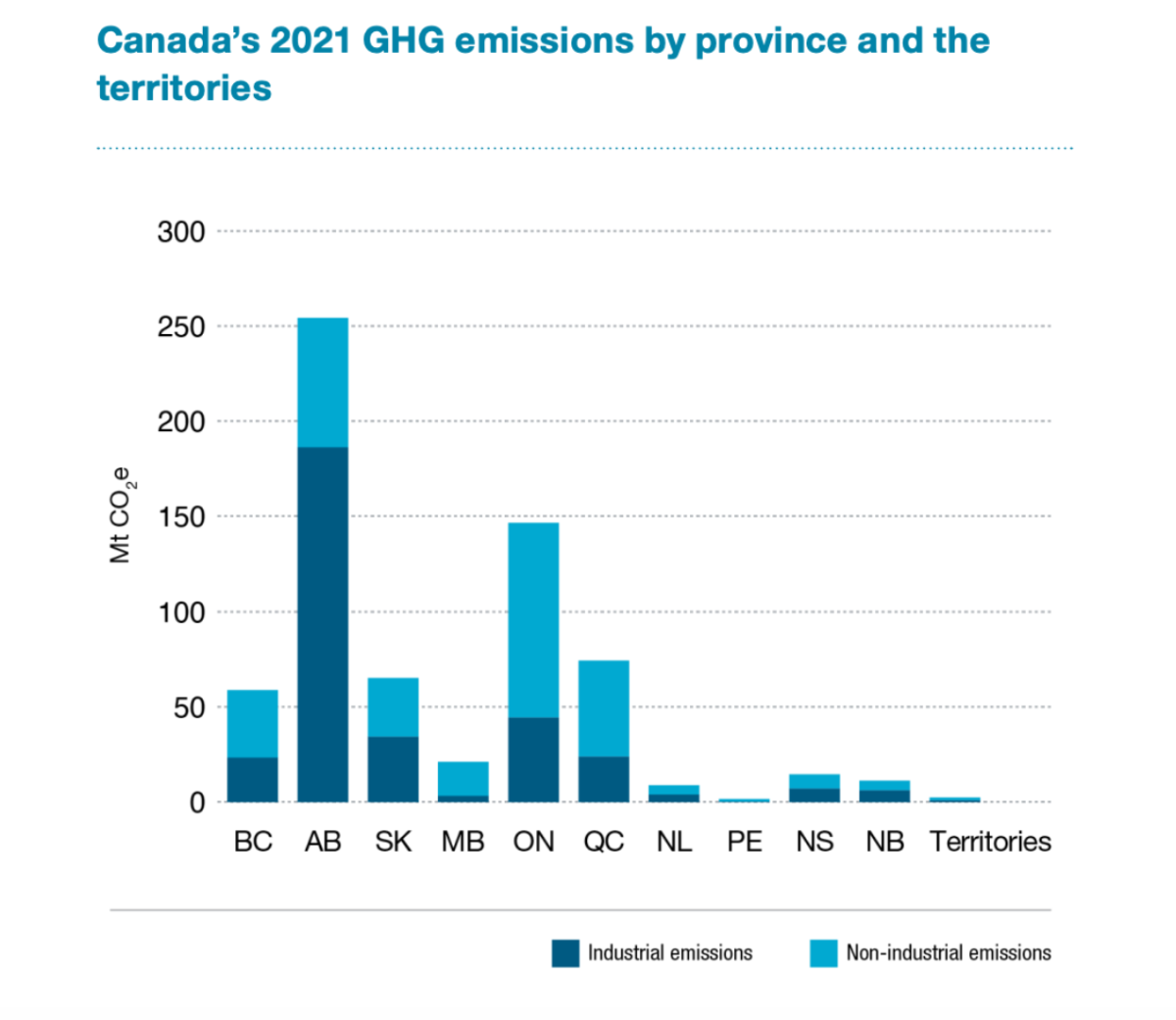

It matters because Alberta spews the most climate pollution of any province. By a large margin. Alberta has about 10 per cent of Canada’s population but emits almost 40 per cent of the country’s greenhouse gases.

Look at that towering bar on the chart, contrast it with the disappointing, even contemptuous response by the provincial government, and you can understand why disappointment has turned to desperation in some quarters. Throwing paint on politicians’ office walls, or soup on paintings (or mammoth tusks). Frustration, anger, even sabotage are in the air.

“You’ve taught me to listen to my anger,” says one member of the crew that bands together in How to Blow Up a Pipeline, just released in theatres. It’s an impressive, gritty film (94 per cent on Rotten Tomatoes), reminiscent of classic heist movies and thrillers. “The climate crisis is the largest existential threat we’ve ever faced,” director Daniel Goldhaber told The Financial Times. “There’s no one system, no one person causing climate change, so how do you come up with a target? Well, it’s the machines that are killing us. That’s the morally defensible target.”

I won’t spoil the ending, but I will say the audience reaction is fascinating — a strangely kinetic silence as the lights come up.

In one sense, the movie is an adaptation of the book by Andreas Malm. But Malm’s book isn’t remotely dramatic fiction or even a how-to as its title might suggest. The book is more of a why-not? A philosophical exploration of the distinction between violence against living beings and damage to property. A history of sabotage and property destruction in successful social movements like the abolitionists and suffragettes. Malm argues these actions get rinsed out of conventional histories.

Some popular podcasts have been digging up more recent history. “How far is too far to stop the planet burning?” asks the host of Burn Wild, as she delves into the worldview of the 1990s’ Earth Liberation Front. Timber Wars takes us back to the old-growth battles in western North America, inspired by Edward Abbey’s 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang.

Eco-sabotage is certainly back in the air today and prominent on the fiction shelves of bookshops. The outlaw group 6Degrees targets oil and gas infrastructure in Stephen Markley’s The Deluge, released in January. The Children of Kali are a shadowy presence through Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future, taking vengeance on private jets and super yachts.

The bookshelf goes on: Hummingbird Salamander by Jeff VanderMeer, the more genteel guerrilla gardeners in Birnam Wood by Booker Prize-winner Eleanor Catton.

We live in very strange times. David Suzuki provoked days of outrage for his observation that pipelines could get blown up if government leaders don’t get more serious against climate change. Richard Powers won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Overstory, in which activists resort to arson. Barack Obama claims the book “changed how I thought about the Earth and our place in it.”

I’m still a bit unnerved by that tense silence after Pipeline. There’s power in culture and desperation in the air.