Shaghayegh Tajvidi: Hundreds of people across Canada died this summer from the heat

NEWSCAST: 486 possible heat related deaths over five days.

Polly Leger: Wildfires erased entire communities from the map within minutes.

NEWSCASTERS: His town, engulfed in flames. We're hearing of just a chaotic run to cars. There are currently over 100 active fires burning in northwestern Ontario.

Shaghayegh: And where there wasn’t fire there was smoke, with air quality warnings in cities across the country.

NEWSCAST: Smoky air is spreading from western Canada all the way to New Brunswick.

Polly: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that this is the new normal. And that's even if we managed to keep global temperatures from rising more than one and a half degrees. For context, we're already at 1.2.

Shaghayegh: The climate emergency can feel profoundly debilitating. The challenges are so huge, and the consequences of doing nothing are unconscionable.

Polly: But according to the IPCC, there's still time to make real concrete changes.

IPCC press conference: If we rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. If we can reach global net zero Co2 emissions around 2050, it is extremely likely that we can keep global warming well below two degrees.

Shaghayegh: From Canada's National Observer. This is Race Against Climate Change.

Polly: I'm Polly Leger.

Shaghayegh: I'm Shaghayegh Tajvidi.

Polly: On today's show, outpacing Montreal’s heat islands.

Shaghayegh: How every building in Toronto is going to get a clean retrofit.

Polly: And The National Observer’s founder and editor-in-chief Linda Solomon Wood sits down with the most famous father-daughter team in Canadian climate action: David Suzuki and Severn Cullis-Suzuki

Linda Solomon Wood: What do you think is the key climate friendly, positive step we can build on?

David Suzuki We've got to cut that lock between the economy driving everything and doing the right thing.

Severn Cullis-Suzuki: We need systems change.

***

Polly: Shaghayegh are you one of those people from Toronto who is extremely into being from Toronto?

Shaghayegh: I mean, I've never been to a Jays game or a Drake concert.

Polly : I've seen that Toronto Versus Everybody shirt you have

Shaghayegh: The exact words, and I quote, are: "Toronto is home" - but actually, very different cities have been home for the last decade.

Polly: Okay, so you probably have a strong sense of connection to some kind of place, like a physical space.

Shaghayegh: In an Iranian family, we drink tea like six times a day, if it's a slow day. So that physical place is usually by teapot and your favorite cozy chair.

Polly: For me, I actually think about the doorframe where we marked how tall we were when we were growing up as kids. It was me, my brother, my cousins. That's the thing I think about when I think about the idea of home. It's more about the building than the city.

Shaghayegh: I think we're starting to sound like a mortgage commercial right now.

Polly : I'm not trying to get you to sign on to like a low finance loan for your dreams! What I'm talking about, and the reason I'm talking about all of this, is because the climate emergency plays out so vividly in the places we call home. And I don't just mean place in a metaphorical way.

Shaghayegh : You're talking literally.

Polly: Yeah. And not just literally like, my hometowns by the ocean and it's going to get engulfed by rising seas, although like that's a real thing, too. I mean, in the physical buildings we live in, and the cities and towns where those buildings actually are.

Shaghayegh: The latest IPCC report gets into this, it says that the very way we build cities is hurting us. And that we're going to be having way more extreme heat events,

Polly: Which means city dwellers, if you're not already roasting in the summer, we're all going to be

Shaghayegh: Today we're getting into all of it.

Polly : We're going back to the heat back to the summer.

Shaghayegh: And we're starting in Montreal.

Polly: Death has become common here during extreme heat waves. This is what they're trying to do about it.

***

Nilson Zepeda: We're going to start just to take a quick look at the parking lot. And to talk about what we are experiencing right now because of the heat.

Polly: With the humidex right now it’'s 37 degrees. You can see it, it's like the air is shimmering. You can feel the heat coming up from the pavement.

Nilson: Let's go with this one. Okay, so right now I'm close to a blue car which is totally exposed to the sun. I'm about to touch it. And I think I could fry an egg. Honestly, it's super hot. It's very intense.

Polly: Nilson Zepeda is standing in a parking lot in Montreal Nord.

Nilson: Here is an empty space. There's no human occupation here, there's only cars.

Polly: Montreal Nord is an industrial neighborhood without a lot of trees. There's a highway cutting through it. There's a lot of squat brick public housing. It also happens to be in a neighborhood where the city had some of the highest rates of COVID deaths. A neighborhood where most people's first language isn't French or English. And a neighborhood where most people aren't white.

Nilson: Here, all the conditions are present to say we are in an "ilot de chaleur". And with all the consequences for human health.

Polly: Nelson's talking about urban heat islands. Cities themselves are actually heat islands, they can be several degrees hotter than the area around it. Heat islands are linked to poor air quality and higher energy use because people are switching on their fans and their AC.

Nilson: A heat island is a space with no vegetation. So in a city like Montreal, you say wow, everything is green. But in fact, it depends on the neighborhood you live in.

Polly: Within cities, you have other smaller, even more sweltering heat islands,

Nilson: The price of the ground, of the soil is cheaper, close to a heat island. So usually if you want to build for example, social housing, those are their spots where they're going to be built. The difference between a freshness Island and a heat island can be between seven and 10 degrees.

Polly: Back in 2018. a heat wave killed 66 people in Montreal. A city public health officer said that Montreal would have seen even more heat deaths last year, if COVID hadn't already killed so many at-risk people.

Nilson: So now we're entering the diner récolte, which is the name of the garden,

Polly: Nelson's part of a nonprofit in Montreal working to green the east side of the city. He took us to La Voisinerie-- it means the neighborhood, or the common space.

Nilson: Can you hear the birds? You have the birds singing, they're also happy to count on these trees.

Polly: A few years ago, this place looked just like that parking lot we were just in. But then Nelson's team partnered with the people that live in the building. And together they started transforming this asphalt alley into a place that wasn't just for cars. Now the building houses a daycare, and the alley is this lush urban garden. Kids play around, there's fruit trees, and the shade makes it noticeably cooler.

Nilson: We are in a natural space with trees, better air, more oxygen. We have birds, so it's kind of a symphony of beauty.

Polly: Dalila Hassid lives in the neighborhood and remembers what this place was like before the garden was built.

Dalila Hassid: - Speaking French -

Polly: She says, “Before La Voisinerie was here, it was so hot, you could even go out. Not children, the elderly, anyone vulnerable. Sometimes you couldn't even breathe. For people who weren't good with heat it was infernal. But now…”

Delila:- Speaking French -

Polly: She says, “We have fun. We have coffee, we talk”. It's like a real community space.

The thing that gets me about La Voisinerie and this space in Montreal is that it's this tiny microcosm. It’s one small heat island transformed into a green oasis.

Nilson: No, isn't it about the temperature. It’s all related. It's all linked. When you are in a heat island, you feel it stronger. So if you have a chronic disease, for example, your quality of life necessarily drops.

Polly: Most major cities in Canada have projects like this, both as a way to keep emissions in check and as a public health priority. Because heat islands can be deadly. One Canadian study found that if a heat island is just two degrees warmer than the area around it, there could be a 4% jump in heat related death.

Another study this time in the US found that reducing heat islands could cut energy use by 25%.

One urban garden and some trees might seem like a tiny drop in the bucket when we're talking about climate change. But Nelson's organization has already done 160 of these projects, putting 10s of 1000s of plants in the ground. Bit by bit, like Nelson says, they're creating freshness islands. It's one of the ways cities can help us get through the heat that we know is ahead.

****

Seth Klein: Hi, I'm Seth Klein, the author of A Good War, Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency. I'm also team lead with the Climate Emergency Unit. And maybe you've read my columns with Canada's National Observer. No one does climate coverage like the National Observer, and I'm proud to add my voice to their work. To support great journalism, subscribe today. Head to nationalobserver.com/subscribe. You can use the code R-A-C-C for a special offer on your first subscription.

***

Shaghayegh: We know that cities need to be designed differently, whether you're talking about heat islands, public transit, or being able to afford housing. But even if we started planning cities in climate friendly, human-centric, new ways we still have the issue of the buildings that are already here.

There are millions of buildings in Canada that are hemorrhaging energy, so much that it makes up 12% of our national emissions. 12%. In Toronto, where I live, this gets even worse. More than half of the city's greenhouse gas emissions come from buildings,

Polly: Okay, but we can't just tear them all down. That'll make the affordability crisis even worse.

Shaghayegh: Oh, absolutely. We can't tear those buildings down. But governments are trying to find ways to at least make them emit less. Toronto's goal is to cut emissions by 65% by 2030. Not to be that Toronto person, but it is one of the most ambitious climate plans in the country.

Polly: Okay, braaaaaaag.

Shaghayegh: How's this for flex: by the end of this decade, all new builds will have to be net zero. And by 2050, the City says all of the existing building stock will be retrofitted to the same standard.

Polly : Okay, so if I get this right, that means every apartment building, every condo tower, single family home, office block, library, school, shopping mall, museum, boutique, dive bar and hotel in the city of Toronto needs to be retrofitted.

Shaghayegh : Yeah. It's a Herculean task.

Polly: Oh, my God.

Stewart Dutfield: Yeah, we're looking at close to 440,000 buildings. It's a lot.

Shaghayegh: Stewart Dutfield is one of the people trying to figure out how on earth this is going to happen.

Stewart: I'm the acting manager of the public energy initiatives existing buildings group,

Shaghayegh: This summer City Council passed a new Net Zero Buildings Strategy, which lays out how it's actually going to make this thing happen. Starting in 2025, energy audits and retrofits for large buildings are going to become mandatory. And it's going to get scaled up from there.

Polly: Sure. But what are these energy retrofits actually look like?

Shaghayegh: It's all the things you've heard before: redo the installation, upgrade the windows, think about using a heat pump, maybe throw up some solar panels. There are government grants for homeowners to help with these kinds of costs.

Polly: Okay, but what if you don't own a home? I'm a renter.

Shaghayegh: This is a huge issue. As we know, Toronto is one of the most expensive cities in the country with an affordable housing crisis. So there's a real fear that if landlords upgrade and older apartment block rents will go up forcing people out

Polly: Also known as rent evictions.

Shaghayegh: Yeah, you got it. Toronto wants to scale up a program that it currently has, focusing on apartment towers, that seems to be working. Basically, the city will give a landlord a really low interest loan to update an apartment building’s envelope. That's the outer insulation. It also keeps landlords out of tenants' actual units. This keeps the building from bleeding energy. So the city says, Listen, we'll help you do this. But...

Stewart: You cannot pass along those costs to the tenants. Because we're able to provide financing and a great interest rate, in return for that we want people to ensure that this is not negatively impacting tenants

Polly: An offer they can't refuse.

Shaghayegh: One reality is most cities don't have a ton of financial options when it comes to slashing greenhouse gases. Even though the ground-game for outrunning climate change is in the places that we live. But in this case, it's not just Toronto versus everybody. Cities are constantly looking to each other for ideas, which is super encouraging. Here's Stewart again.

Stewart: As publicly funded organizations where can we go and share knowledge and expertise? And just implement it if we know it's good and it will work, recognizing their conditions will be different. We often look to Edmonton and Vancouver, really great things happening through Halifax. You know, just rip off and deploy!

Shaghayegh: And there is a lot of potential here since buildings across Canada are responsible for half or more of cities’ GHGs. So buildings might not seem like the most accessible or sexiest solution, but in this context, every single step, like every microstep counts for something.

Polly: It's one thing for new builds to be super well insulated and low carbon. But at a time when housing markets are red hot and so many people are struggling with basic costs of living in this country, should it be up to individuals to really transform their own homes? It's part of the puzzle but it's not the whole picture. Beyond building codes and upgrades, what can we really do to push transformation where we live?

***

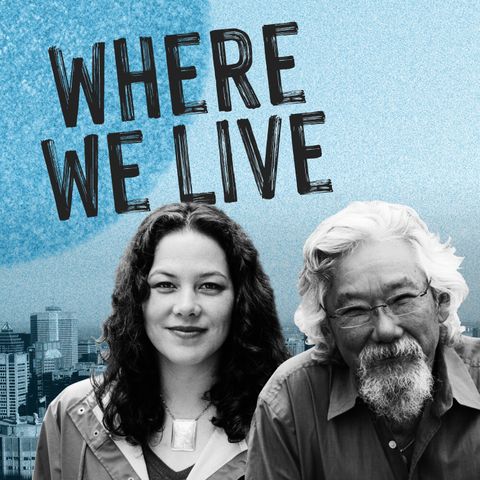

Linda Solomon wood: Hi, I'm Linda Solomon Wood. I'm the founder and editor-in-chief of Canada's National Observer. Recently, I sat down with two climate icons, David Suzuki and his daughter, Severn Cullis-Suzuki. Severn is the new executive director of the David Suzuki Foundation.

David Suzuki: She herself has been an activist since she was a child when she called to say, “Dad, I'm pregnant.”

Severn Cullis-Suzuki: We’re really gonna go there?

David: I said, “Sevm you know, the state of the world…”

Severn: I was hoping for congratulations!

David: But tell tell us what you said,

Severn: I have no idea.

David: You said, Dad, this is my commitment to the planet. My child is my commitment. There is no way I'm not going to fight like mad for the earth.

Linda: In a moment, we'll get to the climate crisis and transforming cities. But first, we've all got vaccines on the brain...

Severn: The lessons we've learned from COVID could directly apply to climate change, and how we actually address a real emergency. We have learned that science and data are key to our way forward. We need expertise to be able to identify risks, and also solutions. We've learned that we are all totally interconnected. And perhaps one of the biggest things is we have renewed agency. If you don't get a vaccine, if you don't wash your hands, your actions could have devastating effects. And this is the same for climate change. So I think right now, there's a huge opportunity for all of us individuals to take advantage of what we are learning right now and apply it properly to the climate crisis that no one can deny is happening.

Linda: What does that look like when it comes to the climate crisis,

David Suzuki: We're going to have to impose demands on reduction of our emissions. And that means we've got to set targets and say: we've got to meet these targets. That's going to cause a lot of kickback if people don't feel a sense that we're in this cosmic crisis.

Linda: So David, you're talking about the cosmic global crisis, yet we all live in cities or towns. In this episode, we talked about heat islands in Montreal, and building retrofits in Toronto. When it comes to the places we live, what do you think is the key climate friendly, positive step we can build on?

David Suzuki: Well, I think we have to stop building cities to serve the car. We have to return to the notion that cities are human created. We originated in the grasslands of Africa 150,000 years ago. We were nomadic hunter gatherers. Cities, which became possible because of the agricultural revolution, where we could stay in one place, cities then became our habitat. Let's make our habitat habitable for humans. And part of that is that we're going to have to live in a way that doesn't exploit the environment, dumping our stuff into it. You know, I meet a lot of parents that say, ‘what can I do?’ and I say, ‘stop driving your kids to school’. It's not just the way we design our cities differently, but our own behavior within the city.

Severn: Our current economic system is promoting the car. One car per person. It's promoting highways, it's promoting the fossil fuel industry, it’s promoting individualistic society. That is totally why you have people protesting in the streets about their rights not to wear a mask. We're now looking at, at The DSF (David Suzuki Foundation), a pilot in conjunction with a lot of different groups about a ‘wellbeing economy’. What does that look like? How are countries like Scotland looking and using a wellbeing focus instead of a focus on GDP. In cities, we have very good dialogue on these pieces, so there's a huge opportunity right now with where people are at.

David: I think the whole idea of having your own property, your own house, and your own little yard that was fostered after WWII, when the suburbs just exploded. We can't do that. Of course, one of the problems we face is that we're pricing the ability to live in a city like Vancouver out of the range of a lot of the people who are looking for jobs within the city. So the housing issue is a big one. But to me, you're touching on this Sev, it's the economic system itself.

Linda: Severn, up until recently, you've lived in Haida Gwaii. David, you spend a lot of time on Quadra Island. These are not bustling cities. They're fairly remote. What's the most innovative thing you've seen happen in your communities?

Severn: The innovations that inspire me are ancient. So I live on Haida Gwaii. And living on Haida Gwaii for the past 14 years, I've deepened my understanding of traditional things like the Potlatch. Which is something that happened in communities up and down the coast, not only in Haida Gwaii, so in different cultures a bit differently. But this was an incredible system and way of redistributing wealth. These totally different ways of existing as humans are right here, there are opportunities for a different way of existing, and we can learn so much. On Haida Gwaii, there's potlatching that continues today. I also lived in a community where the band council in Skidegate provided every home with a heat pump. We saw this amazing reduction of our emissions through heat pumps. These are very sophisticated people who are looking for solutions-- but the combination with ancient practices that are fundamentally successful...Amazing.

David Suzuki: And as individuals, as cities, we've got to stop, cut that lock between the economy driving everything, and doing the right thing. I don't know if there is any magic bullet for how we're going to develop cities, that's for people who are experts in that. We just have to make the commitment that our cities have to look towards a zero footprint, and then find all of the creative abilities.

Rural communities, we can't go in and tell them. They've got to help us, and tell us what their needs are, and design a way for them to live in rural communities. But the most important thing is to say: we can't go back to doing it the way we were. We can't let the economy hamper us in doing the right things. And let's get the creative ability of people in various communities to come up with the solutions.

Linda: What I hear, and what both of you are saying is you're talking about a kind of different economy, and you're talking about the power of community. I wonder what you both think about the expectation of individuals, like homeowners, to do a full energy retrofit on their home? How much of this is going to be solved by individual actions?

Severn: We need systems change. We've all been struggling with this our whole lives. Do you vote with your dollar? Is it up to the consumer? And yeah, I've taken it on, you know, lugged around my non-disposable coffee cup. Dad loves the bus. You know, we're all doing all those things. And we're realizing it is not enough.

When I became a mother, I realized, you know, we as activists, environmental activists, and advocates, were asking people --and it's usually mothers, they're the ones that care about the future in such a visceral way. We're asking people to do all their homework, do the research, and then make the tougher decision. Because all the things that are right for the planet are more expensive, are more difficult, take more time.

I mean, our whole society is built towards destroying ecosystems, essentially.

So when you live in that context, it's very, very hard. And I think that that reality is why so many of us who are exhausted with this paradox, that's why we're exhausted because we're living in a paradox.

Linda: We’re exhausted with the paradox.

Severn: And we live it every day. And we know that we're contributing to the end. So we need systems change, and we need our governments to help us out here, and make being a Canadian not congruent with destroying the climate.

David: Yeah. I think that corporations love to say, ‘well, it's up to you, we just serve what you want. It's up to you to choose your product’. They love that. But they're spending billions and billions of dollars telling you, you need these things that we never even even knew that we wanted. And suddenly they're creating the want.

We need, as Sev says, big systems change. Because we're all trapped within an economic and a political system that is itself destructive. I think that what we need is the kind of response that we get when we have a crisis that you can't avoid. And that is what we saw in World War Two. And I love what Seth Klein has done with that with A Good War. Because once you suspend all of the politicking and all of that, and say ‘we've got an existential crisis, we have to win that’ and throw everything into it, then all of the the system's constraints disappear.

Severn: Just like we saw in COVID. Everybody's been saying, oh yeah, this is a climate emergency. Well, we just saw what a real emergency response was right now, this year,

Linda: When you think about the crisis, and you know, everything we're facing in the world right now. And you think about your grandchildren, are you afraid?

David: I'm terrified. You know, we've started the experiment..

Linda: --The experiment?

David: The experiment with the planet. We're changing the chemistry of the atmosphere. And we're doing it in a way that has never happened in nature, we're doing it so quickly. If we stopped all emissions today, it will still take over a century to find equilibration. We're destroying the only real safety net we have, which is the web of living green things all over the planet.

Linda: And extinction is final. Extinction is one of the only things that is final.

David: Extinction is final, but it's normal. Extinction was necessary for life to evolve. Without extinction, you get no evolution. But what is not normal is the rate at which we have now induced extinction

Linda: And Severn, as a mother, when you think about your kids living through the changes ahead, are terms like hope or fear even useful for you?

Severn: Well, I'm definitely afraid. But for me, the conversation about hope is really about agency. I'm not hopeful in the way of, you know, ‘I hope climate change is stopped’. Because it can't be stopped, it's going to be unfolding now and it's just a matter of degree.

But I'm currently doing my PhD in anthropology. And I find so much inspiration in Indigenous cultures around this planet. Right now, there are so many cultures that can show us different ways of being human. And they have existed for thousands of years. Indigenous people, for them, the extinction event that we are just as a colonial society coming on into awareness about, for them it's been happening for 500 years.

And what the experiment to me is cultural. We suddenly have for the first time a globalized economic culture that is being imposed on humanity. And look at the ramifications. It's having terrible ramifications on the entire atmosphere, on the entire ecosystems.

So for me, I'm really focused on what currently is working and has been working for millennia. And what can we as a colonial society, as a globalized economic culture, what can we learn from what exists right now? And has survived all kinds of crazy events.

I mean, it's been so humbling for me to live on Haida Gwaii nd to think about people who have survived smallpox-- 95% and an over mortality. I mean, that pandemic, that epidemic, was the end of the world. And now you know, here it's been really in high relief dealing with COVID and the current pandemic to just think about that time at the turn of the century for them.

So we have so much to learn about resilience, about survival from those who have survived the end of the world. And they are Indigenous people, and they are here, they are alive, they are vibrant, and they are going to have to be the ones that we look to, to find our way through. And so it for me, that's what gives me a sense of agency. And I see a path for humanity to get through this bottleneck. And that's the hope I have for my children.

Linda: David, Severn, thank you so much for being with us here today.

David: Well, thank you very much.

***

David Suzuki Archival: If we continue to look at the land of the world around us, just in terms of dollars and cents, we are going to destroy the very things that make that land so precious to us.

Shaghayegh: There's an inherent tension when it comes to climate solutions. Are more traditional neoliberal financial incentives, like grants to help you renovate your home, is that enough?

Polly: Or is that too much burden on the individual? We know we need to fix what we have. Green urban heat islands, retrofit our existing buildings stock, change building codes for new construction so that they emit less.

Shaghayegh: And we also need serious systems change, like Severn Cullis-Suzuki says. The status quo, just tweaked to include heat pumps and better windows isn't going to get us across the finish line. We need to throw everything we have at this

Polly: The cost of doing nothing is far more extreme than the cost of renovations.

David Suzuki: This is our moment. This is not going to happen overnight.

Polly: Our conversation with the Suzukis was so good we're going to release the whole thing for you as a bonus episode.

Shaghayegh: Make sure you subscribe to the show so you don't miss it and your podcast feed.

***

CREDITS

Polly: Special thanks this week to our guests, you can find more of their work in our show notes and way more climate writing at nationalobserver.com

Shaghayegh: Canada's National Observer wouldn't exist without founder, and editor-in-chief Linda Solomon Wood. This show was produced and edited by me, Shaghayegh Tajvidi.

Polly: And me, Polly Leger. With field production this episode from Ellen Payne Smith and Elysse Deveaux in Montreal

Shaghayegh: Final audio mix by Tyler Gillis and the Aftertouch Audio team. Music this week by Blue.sessions and Martijn de Boer

Polly: Artwork by Ata Ojani And thank you to our promotions and comms team, Suzanne Dhaliwal and Luke Ottenhof. Fact check by Dana Filek-Gibson.

Shaghayegh: Race Against Climate Change is a joint project from Canada’s National Observer and the Canadian Centre for Journalism. You can follow us on twitter -- and we’ve revived our Instagram! @NatObserver.

Polly: If you like the podcast, please subscribe and give us a rating wherever you find your podcasts. It really helps other people find the show!