Behind bars: Canada's fur-farmed mink and fox

All images and footage courtesy of the Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals unless otherwise specified. Above, a mink farm in B.C.'s Fraser Valley.

Animal advocates say Canada needs tighter legislation to protect fur-farmed animals, but other industry stakeholders disagree. Caught in between the battle are Canada's mink and fox, forgotten on farms while the debate rages on.

Animal welfare scientist Sara Dubois was horrified when she first set foot on a fur farm.

In row upon row, roughly 70,000 mink squirmed in cages the size of two shoe boxes as heaps of their own excrement mounted on the floor beneath them. Many were missing limbs, digits and ears, and one animal — mysteriously paralyzed — had to be euthanized on site.

"It was a shocking experience to say the least," she recalled, speaking with National Observer over the phone.

"There were animals with wounds in a hospital shed that weren't being adequately treated, there wasn't a proper plan of medical care, there was no [health] record of the animals or appropriate euthanasia being used."

Based on this description, Dubois could have been visiting a farm in China — a country notorious for animal cruelty associated with the fur trade. This animal cruelty investigation which Dubois was part of, however, took place last summer in British Columbia's Fraser Valley.

No charges were laid against the fur farmer in question, and, in accordance with provincial law, he was given time to "clean up his act." He complied, effectively cancelling the cruelty case.

"I think the majority of the public doesn't know what's going on," said Dubois, chief scientific officer for the B.C. Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (BC SPCA).

"This is actually happening [in Canada], and — in our belief — without proper independent oversight."

Despite this country's frequent criticism of animal welfare standards elsewhere in the world, Canada itself has no federal legislation governing the upbringing of fur-farmed animals.

It's up to the provinces to adopt their own animal welfare laws, and, according to animal advocates, most provincial governments are failing — particularly B.C.

Loopholes in the law

Above, a filthy Ontario fur farm discovered during an unofficial 2014 investigation.

Loose provincial laws regulating fur farming, standards of care, and enforcement make it possible for some fur farmers to bend the rules.

Canada is home to a robust fur-farming industry of mink, fox, marten, fisher, chinchilla and a handful of other fur-bearing species. Last year, Statistics Canada counted more than 230 registered mink farms and 50 registered fox farms across the country, which bred a combined total of more than three million animals.

Fur farms are regulated provincially and in 2013 the National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC) released new codes of practice for the care and handling of farmed mink and fox.

These codes outline minimum requirements for housing, security, feed, water, health, husbandry, euthanasia and transport, but so far, only Newfoundland and Labrador have legislated them.

The B.C. government, which has not adopted these codes into provincial law, uses them as guidelines.

“By not putting that in [the Fur Farm Regulation], they are allowed to go into your farm and inspect and use their discretion,” explained Bryce Engebretson of the B.C. Mink Producers Association (BCMPA).

“If the mink are doing well and you’ve shown that you’re caring for the mink, and the veterinarians come in and looks and the mink are doing well, they’ll say ‘you’re good.’”

Used as a "benchmark" only, the codes of practice have no legal implications. This means farmers can get away with bending the rules, even if only by several inches of cage space.

This makes the law "woefully inadequate" according to Lesley Fox, director of the Vancouver-based Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals.

"There's nothing that has teeth," she lamented. "It just comes down to the fact that there’s no recourse."

Fox pointed to the 2014 case of the mink farm in B.C.'s Fraser Valley, where BC SPCA animal welfare scientist Sara Dubois found animals living in "horrific" conditions, despite government claims that fur-farmed animals in B.C. are treated with "due care and respect."

Government trailing behind

In an email to National Observer, B.C. Ministry of Agriculture communications manager Robert Boelens said the province's current legislation is sufficient to govern fur farms, including the care of mink and fox.

He did not answer questions about why the ministry had not ratified the NFACC’s new mink and fox codes or whether it ever intends to, but he did highlight new amendments to the Fur Farm Regulation that require annual government inspection of fur farms as a condition of re-licensing.

"The B.C. government does not tolerate any mistreatment of animals," he said.

"Fur Farming is a licensed agricultural activity in B.C. and the B.C. government has legislation and regulations in place that require all animals in British Columbia to be treated with due care and respect."

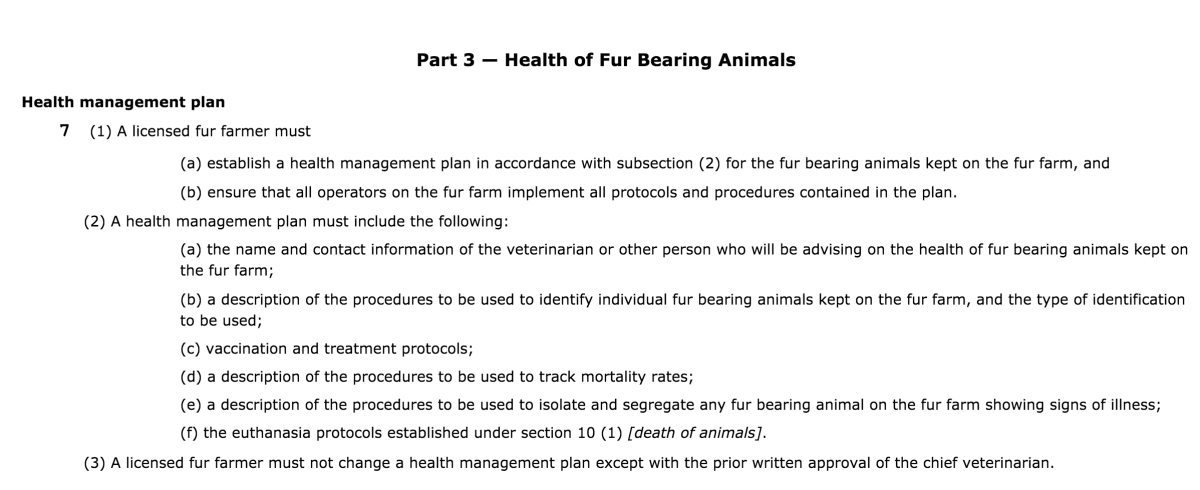

A closer look at the Fur Farm Regulation, however, reveals no clear minimum standards of care for the animals, including recommended enclosure sizes, euthanasia methods, environmental stimulation or environmental management.

As seen below, it explicitly states that farmers require only "a plan" — language that animal advocates criticize as vague.

Without strict enforcement of the NFACC codes, said Dubois, she places little faith in the B.C. government's current legislation:

"There is no third party or auditing system of mink farms right now. The reality is that the Ministry of Agriculture is not allowing the BC SPCA into farms to go and look at the practices."

During Dubois' inspection last year, a Ministry of Agriculture representative told her that the mink farm's horrible conditions were "middle of the pack" in comparison with the province's other fur farms.

The B.C. SPCA subsequently asked for access to the rest of the province's 14 or so fur farms, but the provincial government did not issue a formal response. The organization can only inspect farms after a complaint has been made, and unless it is invited in by the fur farmer, it requires a court-ordered warrant.

Dubois also clarified via email that if the B.C. SPCA inspects a farm, unless animals are in critical distress and need to be removed immediately for vet care or euthanasia, the farmer has "an opportunity to fix the issues in the complaint within a specified time (can be 24 hours, a week, whatever officer requires)."

As long as they comply, cruelty charges are not usually laid, she said.

APFA director Lesley Fox further scoffed at B.C.'s Fur Farm Regulation inspection amendment, which she called a "giant conflict of interest."

"The government sets the rules for fur farms, the government has a financial interest in fur farms, and the government is tasked currently with the enforcement and inspection," she said.

Broken promises

A caged fox on a Quebec fur farm. Photo obtained in 2014.

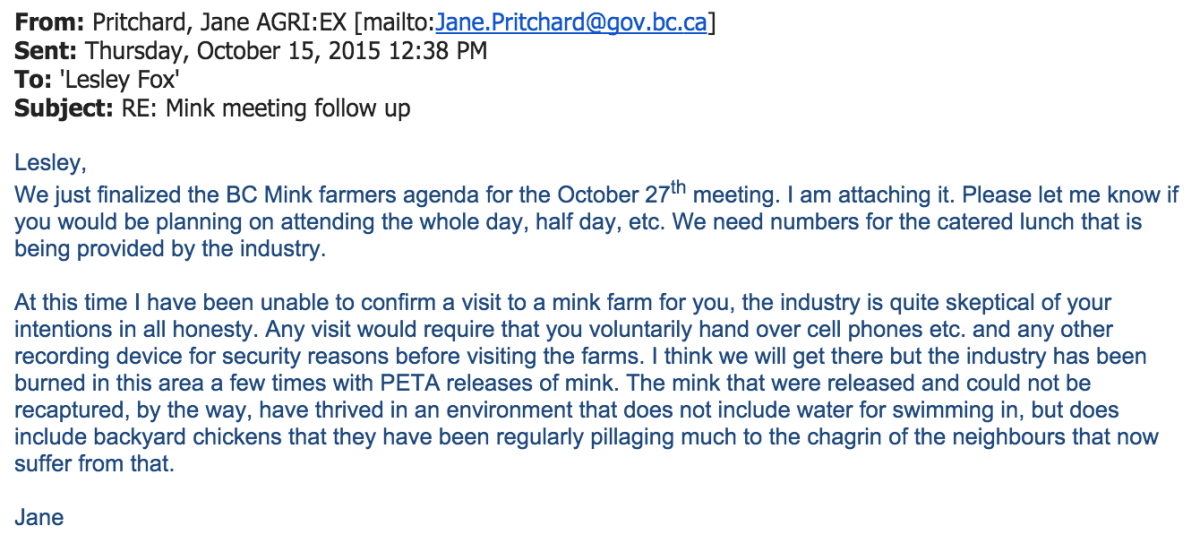

The B.C. government promised to escort an animal rights activist onto a B.C. fur farm, but later reneged.

On Oct. 13, APFA director Lesley Fox met with B.C. Agriculture Minister Norm Letnick, his team, and the government’s chief veterinary officer, Dr. Jane Pritchard, who joined in over the phone.

It was the first audience the association had ever received despite decades of lobbying, and Pritchard not only offered to bring Fox to an Oct. 27 fur-farm industry meeting, but to personally escort her onto a local mink farm.

"The gesture was incredible, and we felt really encouraged," said Fox. "At first, it really looked like a genuine offer to have all parties in the interest of animals and animal welfare get together and discuss the issues."

Within 10 days of the meeting however, both offers were rescinded.

On Oct. 23, Fox wrote Letnick about the fallout, encouraging him to "take immediate action to demonstrate a full commitment to involving all stakeholders in an ongoing, truthful and open dialogue about B.C.’s fur farms."

She has not heard back from the Ministry of Agriculture since then. Its communications manager, Robert Boelens, would not comment on the department's halt in communications with APFA.

"Ministry staff have followed up with them directly since [the meeting]," he told National Observer, referencing Pritchard's emails.

"The Ministry of Agriculture offered to try and arrange a tour for an AFPA representative to visit a farm, but was not successful in our efforts to arrange a tour."

National Observer has asked for all government records of exchanges between the ministry and APFA under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, and is waiting for a provincial response.

A different version of the story

In her emails, Pritchard suggests "distrust," skepticism and a "bad relationship" between APFA and B.C. mink farmers as the reason for withdrawing her offer to connect Fox with local fur farmers.

Bryce Engebretson, a B.C. mink farmer and member of the B.C. Mink Producers Association (BCMPA), however, told a slightly different version of events.

"Personally, I have never heard of anyone asking to come onto a farm, or join a meeting and then have the offer rescinded," he said."Maybe that was the government."

In fact, as far as Engebretson knows, the BCMPA has never been contacted by an animal welfare group for a candid conversation.

Fox also confirmed that she has never been in touch with the BCMPA.

So, what "bad relationship" with APFA was Pritchard referencing?

National Observer called and emailed her for comment, but she directed the inquiry to the Ministry of Agriculture.

Engebretson, meanwhile, said he would be happy to escort an activist onto his family farm in Abbotsford, B.C. provided their intentions involve genuine and productive industry discussion:

"If someone was really wanting to learn, and they didn’t have motives where they were trying to be confrontational and malicious, then of course, I would have no problem with that," he told National Observer.

The fur farmer in your backyard

A fur farm in Nova Scotia. Photo taken by activists in 2014.

There are bad eggs in every basket, but not all fur farmers should be painted with the same brush, say Canadian fur producers.

According to the Canadian Mink Breeders Association, Canada's mink and fox farms produce nearly 3 million pelts every year across eight provinces, pumping nearly $300 million into the economy.

Statistics from the Fur Council of Canada (FCC), which represents the industry's stakeholders, say the entire fur trade is worth about $800 million and employs more than 65,000 Canadians.

"Fur is made with traditional craft skills, not machines. It's a heritage industry," said FCC executive vice-president Alan Herscovici. "All the farms are family-owned farms."

The pro and anti-fur debate has raged on for years. Meanwhile, said Herscovici, industry, government and activists go back and forth, leaving farmers and trappers in the lurch along with the animals themselves.

"I think it's become very ugly, with some of these debates," he told National Observer.

"A lot of the campaigns speak in the name of compassion. And yet we're showing so little respect for other people, people on the land."

He believes the fur industry in Canada is very well-regulated and encourages engagement between stakeholders, government and animal advocates.

The fur farmer in your backyard is not a bad guy, he said, and most trappers and farmers abide by industry codes of practice, and in many cases, exceed them.

"The more people who know about the fur trade, the more respect people will have for it," he explained. "We have to reach out more about who the industry is."

Engebretson — a foreman on his family mink farm in Abbotsford, B.C. — agreed completely.

“I look at the mink every single day and if anything is in pain or hurting, we give it medication and painkiller," he explained. "If it’s too far gone, we euthanize it immediately.”

Just as law-abiding animal advocates shouldn't be painted with the same brush as those who illegally release mink on farms, he said law-abiding fur farmers shouldn't be grouped with any farmers who neglect and abuse their animals.

"It's been a very touchy subject for a long time for some people," he said, of the anger and sometimes hatred that is often directed toward fur farmers. "We're doing everything we can to make sure that we're up to the standards of the government."

Engebretson's own family farm will be inspected by the Ministry of Agriculture every year prior to re-licensing to ensure the government is happy with the conditions of the farm and the health of the animals.

"It's up to us to keep it that way; we're not afraid of anything, we're proud of what we do. And we feel that we're going to keep everything up to code."

The future of fur-farmed mink and fox

Industry stakeholders say the future is bright, but animal activists disagree.

"Right now, as you and I speak, those minks are being skinned for fur," said Fox, speaking over the phone with National Observer as she pored over dozens of photos of B.C. mink farms in the Fraser Valley.

Some of the mink are chewing at the bars of their cages. Other mink, resorting to cannibalism, are chewing on each other.

Most mink are pelted in November or early December, killed by exposure to carbon monoxide — if the farmer is following the NFACC Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farmed Mink.

In 2014, a group of concerned citizens provided APFA with footage from nine different fur farms across Canada that clearly showed these codes were not being followed.

"I think the public wants reassurance that we're doing everything we can to maximize animal welfare," said Fox. "There’s really no protection for these animals, still."

The association filed cruelty complaints in B.C., Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia, most of which fell through the cracks of the bureaucratic process.

When the B.C. government stopped communicating with Fox, her concern for the future of fur-farmed animals rose to new heights.

"I feel like talks have broken down and that the government is fiercely protective of this industry," she said. "At what point is it transparent?"

A secretive fur farming industry

Since 2011, SPCA branches across Canada have recommended more than 800 provincial and Criminal Code charges of neglect and cruelty against animal owners, but only one Canadian fur farmer has ever successfully been charged.

In January 2015, Jean-Luc Rodier became the first fur farmer in Canadian history to face cruelty charges, in this case relating to 90 foxes, 10,000 mink and two dogs at his facility in St-Jude, Que. Rodier pleaded not guilty to all charges, but if convicted, he faces up to 18 months in jail, $60,000 in fines and a lifetime ban on animal ownership.

Some animal advocates may celebrate this as a victory, but Fox isn't as encouraged. The fact that only one fur farmer has ever been charged with cruelty is proof there haven't been enough inspections, she said.

"There aren't any complaints about fur farms because no one sees them," she insisted. "This industry is extremely difficult. And now to have no dialogue or follow up [from government] is really disheartening."

Engebretson, on the other hand, has a much more optimistic view of the future for Canada's fur-farmed mink and fox, especially in B.C.

He rejected the idea that secrecy is a quality of the fur farming industry, and said transparency is a virtue of his family farm:

“I have nothing to hide, personally," he told National Observer.

"I’m really for people being transparent with what’s going on. It doesn't make any of us who follow the rules and really care about the animals and are proud of what we do look very good.”

He further stated that the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture tightened up the Fur Farm Regulation as a direct result of 2014 mink farm cruelty investigations, and that more legislative changes are on their way.

The codes are coming

"The [NFACC code of practice] will eventually be 100 per cent enforced," Engebretson explained. "Dairy farms have one, chicken farmers have one, pork farmers have one — it just takes a bit of time for the [new] code to be ratified."

When the B.C. government inspects local fur farms, he said, it uses the NFACC code of practice as a guideline anyway, and issues licenses based on compliance with those regulations.

He couldn't speculate as to why the Ministry of Agriculture would not discuss this with National Observer, but said B.C. is at the forefront of protection for farm animals in Canada.

"As British Columbia mink farmers, we are held to a very high standard," he said.

"As for as farmers that aren’t up to code in British Columbia, the government will be taking care of that."

Based on the weak track record of fur farming cruelty charges in Canada, however, animal welfare advocates have a little less faith. Until provincial governments step up their game across the country, advocates fear the animals will remain forgotten on farms.