Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s decision to abandon electoral reform, laid out last week by his newly-minted minister of democratic institutions, is a cynical and calculated step.

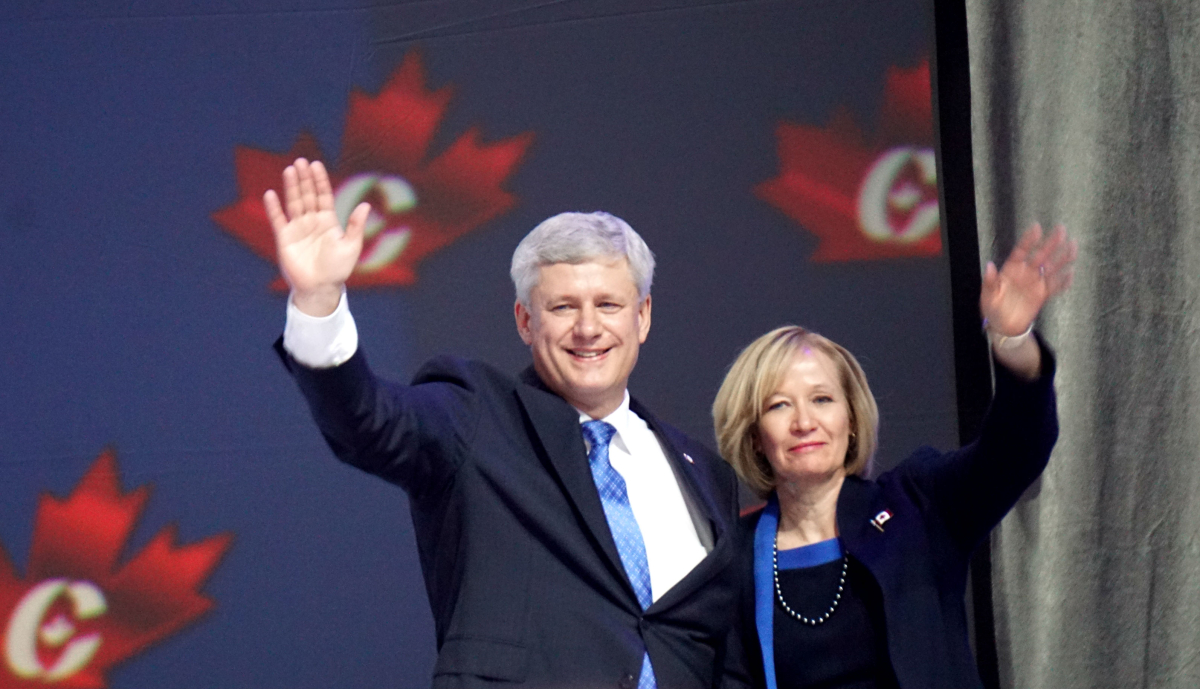

It's the kind of action we became used to under his predecessor, Stephen Harper, and it holds Canada in the minority of countries that still use the “first-past-the-post“ system – a regrettable legacy from the days of Britain’s colonial empire.

Taking this step – and saying "consensus has not emerged" (read: Canadians don’t care) – suggests that Trudeau is comfortable with a system that contributed to the election of a man like Donald Trump. It also cemented the rule of Stephen Harper for nine straight years, a man who, by the end of his administration lacked support from many of his own party members.

The implications, therefore, are much darker than an obscure back-room resolution by the Liberal caucus.

More unfair elections to come

This decision signals continued unfair elections, in which minorities usually win majorities and in which the majority of voters are disenfranchised. It signals an end to a promise of consensus-based decision-making, more odious distortion of democratic principles and a need for strategic voting.

Most importantly, the norm of unfair elections means that the locus of political action will continue its slow but steady movement out of the formal structure of government and Parliament, and back into the streets, communities and inevitably into the courtrooms of the nation.

Just look south of the border if you want to see where Canada will soon be headed, given this regrettable turnaround. The protest movements in the U.S. have mounted steadily since Trump's election.

(The U.S. presidential election is carried out by a peculiar system of state Electoral Colleges, which override the popular vote; these Colleges are, however, heavily influenced by the first-past-the-post system, which determines the election of every member of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives.)

I personally voted strategically in the 2015 election, because I was deeply distressed by the possibility that Stephen Harper would be reelected with a majority, the first-past-the-post system forces such behaviour. In past years, I have never voted strategically, feeling that it was better to stand for what one believed than to hold one’s nose and vote for a party that was a second or third choice.

In 2015, I felt I had no choice and hoped I'd never have to do it again.

After Trudeau's flip-flop, it will be hard to take the act of voting seriously again, because election outcomes will continue to be deeply unrepresentative of the full spectrum of Canadian political values. Although Trudeau is clearly more acceptable to most Canadians by a country mile than his predecessor, decisions like this reveal his party’s willingness to engage in self-serving gamesmanship, probably counting on the brouhaha in U.S. politics as a public distraction.

It also indicates that this country, like the United States, will continue to be vulnerable to an ideologue who captures the public attention, even one who embraces misogyny, racism and hard-line nationalism.

How we got here

Before the 2015 election, this is what the Liberal website – replete with a photo of the prime minister in full flight – had to say about elections and electoral reform:

“We will make every vote count. We are committed to ensuring the 2015 will be the last federal election conducted under the first-past-the-post voting system. We will convene an all-party Parliamentary committee to review a wide variety of reforms such as ranked ballots, proportional representation, mandatory voting and online voting. This committee will deliver its recommendations to Parliament. Within 18 months of forming government we will introduce legislation to enact electoral reform.”

Nothing could be clearer: electoral reform, during the last election campaign, was on the way. It was just a matter of time.

Then, a month before the special House of Commons committee on electoral reform finished its deliberations on Nov. 28, 2016, Trudeau started hinting that he would only change the electoral system “if Canadians are open to it.” Some speculated that this shift was related to the fact that the Liberal Party’s favoured system, the so-called “ranked ballot” system, was not supported by either experts or committee members. This system, which, with current voting patterns, might have changed very little (except possibly future voting patterns) did not gain much traction in the special committee’s deliberations.

Then a few days later, the committee released its report, emphatically recommending that Canada move towards a proportional voting system – as suggested by the majority of expert witnesses who came before the committee. It also recommended a referendum, which the Liberal government was supposed to (for very good reasons: they have rarely been used, and they have never worked particularly well as they are so subject to manipulation).

But nothing bound the Liberal government to do anything it absolutely didn’t want to do. The field was open – to any form of proportional electoral design.

A few days later, the government sent out a questionnaire, called “My Democracy,” which contained 30 questions with no opportunity to indicate a preference for one electoral system over another. Nonetheless, a majority of respondents favoured collective decision-making, co-operation between parties and direct policy negotiations between parties – all hallmarks of proportional electoral systems.

Finally, on Feb. 1, it was up to Democratic Institutions Minister Karina Gould – a junior minister barely three weeks into her new mandate – to toss out the process of electoral reform, having already aroused suspicions a few weeks earlier that this might happen. Gould, who has an impeccable record of advocacy for social justice prior to running for office, had already demonstrated her willingness to sacrifice principles for political expediency; in August, 2015, when she declared her election candidacy, she carefully deleted social media messages that criticized development of the oilsands and pipelines.

Despite the fact that over 80 per cent of experts presenting to the special committee had recommended a proportional system, and four of five Canadians involved in national consultations had said the same, Trudeau and other liberal leaders claimed that there was no consensus (a conclusion, in my opinion, that ranks up there with Kellyanne Conway's "alternative facts").

So far there has been no word about electoral reform being simply postponed, or any hint of a timetable for recapturing the momentum generated by the committee’s deliberations and months of public's engagement'

Why FPTP is so hazardous

The first-past-the-post system generates unfair and distorted outcomes.

The Harper government, for example, was elected in 2011 with 39.62 per cent of the votes, which won them 166 seats in the House of Commons. The Trudeau government was elected in 2015 with 39.5 per cent of the votes – a mere 0.12 per cent difference.

In both cases, the party that came second in each election received votes from nearly one third of the voting public.

Many Canadians would agree that the two governments were and are poles apart, both in attitudes and conduct, yet under the current system, they each came to power with support from fewer than two of five voters.

The first-past-the-post system tends to generate such major swings in government behaviour, based on incomplete support from the electorate, because winners tend to be minorities. In the recent US election, the contrast between the two candidates and their platforms – Trump the rogue neophyte, intent on sowing discord, and Hillary Clinton the establishment favourite, focused on maintaining the status quo – left voters no opportunity for nuance, variety or detail in their voting choice.

This is because first-past-the-post elections are really designed for a two-party system, and if there isn’t one, it leads inexorably to it. It impels voters towards strategic voting. Voters calculate how they will vote not simply on the basis of candidate positions but also on the likelihood of a candidate being elected.

Voters make compromises about who they will vote for, to try to make their vote count.

Under the current system, then, some voters have three disagreeable choices: don’t vote at all; vote for a candidate they don’t really want to elect, but who is likely to get in and is less unsatisfactory than the others; or vote for the party in which they believe, knowing that their candidate will go down to defeat.

Weird outcomes of FPTP

The fate of the Green Party in the U.S. illustrates the imbalance. Despite having a credible leader and despite receiving 1.45 million votes – over one per cent of the popular vote – Greens didn't win a single seat in November 2016.

In Canada, bizarre outcomes from first-past-the-post abound.

In the 1993 Canadian federal election, the Bloc Québecois received 13.5 per cent of votes – 1,846,024 to be exact – but received 49 seats in the House of Commons. It became the Official Opposition because its supporters were concentrated in one part of the country. The Progressive Conservative Party, which had had 156 seats prior to the election, wound up with only two seats, even though it received just over 16 per cent of votes – roughly 340,000 more than the Bloc.

As in so many elections before and after, the party that won that election – the Liberals – did so with a mere two fifths of the votes cast.

Here’s an even crazier example.

In 2008, the Green Party received 937,613 votes, comprising 6.8 per cent of the votes cast. It gained no seats in the House of Commons – zero per cent of the total seats available. The Bloc Québecois received slightly more votes – 1,379,991 (just under 10 per cent) – but earned 49 seats, once again because its support was entirely concentrated within one province. By contrast, the New Democratic Party received nearly twice as many votes as the Bloc Québecois (2,515,288, or 18.2 per cent), but earned 22 fewer seats, because its voter support was diluted by location.

Here's where that leaves us

The decision by the Liberal Party to stick to the current voting system will have far-reaching consequences for democracy. It will, of course, deepen the level of citizen cynicism, especially among young people, as the commitment to this process was so utterly explicit.

Going back on such a clear-cut commitment without any expression of regret, or any indication of intent to revisit the matter in the future, is high-handed and inexcusable. More importantly, this decision condemns future generations of Canadian citizens to the vagaries of a system that is clearly outmoded in today’s multifaceted, interactive and collaborative world.

If disapproval of this decision is intense and sustained enough, the Liberals (or future governments) will feel pushed, at some point down the road, to open the door again to electoral reform. That means ordinary citizens need to keep the memory alive of what Green Party leader Elizabeth May described as a betrayal that involved “our feminist Prime Minister [throwing] two young women cabinet ministers under the bus on a key election promise.”

Young generations depend on those in power today to set up a system that is equitable and balanced. They don't want — and can't afford — to be disabled by cynicism. They want a system that will allow them to work together to constructively solve the problems created by humankind during the era in which we have started changing the physical functions of the planet.

In this tumultuous time, we need to choose a different path – all of us working together. Sadly, in this case, Canada’s prime minister has ignored our need.

Editor's Note: This piece has been corrected from a previous version that said in the 2008, the Green Party of Canada took one seat. They did not, in fact, take any.

Comments