Fewer than 20 per cent of employees at Canada's health and public works departments received mandatory training on ethics, values and conflict of interest between 2013 and 2016, a report from Canada's auditor general, Michael Ferguson, has found.

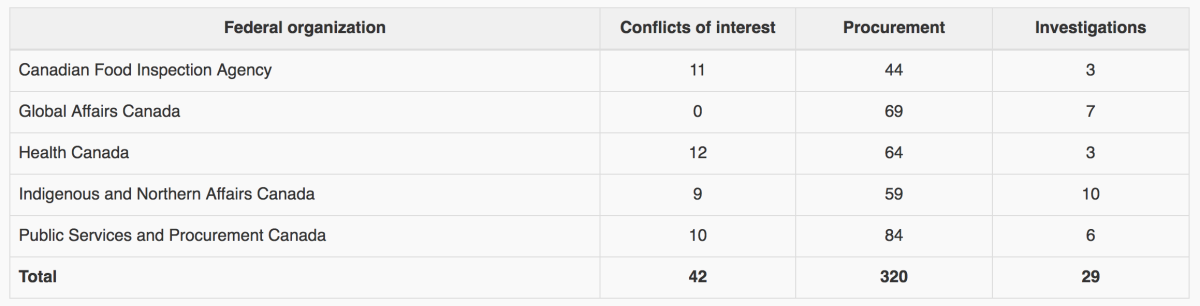

The audit on fraud risk management published Tuesday examined both Health Canada and Public Services and Procurement Canada, along with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC). It examined how well the five organizations were equipped to deal with the risk of fraud between April 1, 2013 and October 21, 2016.

While these departments and agencies all have plans to manage fraud, these plans weren't always put into action, Ferguson's office found. In some cases, the organizations failed to implement standard controls, such as justifications for sole-source contacts, in addition to staff training on ethics, the report stated. At the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 34 per cent of employees received the required training, and within INAC and GAC, those figures could not be calculated.

Many conflicts of interest declared by employees also took too long to resolve, said auditors, who completed the assessment in early March.

“Overall, the organizations had appropriate governance structures to help them manage their risk of fraud, but some organizations did not use a strong enough approach to assess those risks,” said the report tabled Tuesday. "...none of the organizations made sure that the specific controls we looked at worked as they should have.”

Three of five conduct fraud risk assessments

Fraud is inherent in all federal government programs, according to the Office of the Auditor General, and manifests in various ways. An employee could, for example, misuse his or her influence in a business transaction for personal benefit, accept a bribe to influence a decision, or provide sensitive information to an external party for money.

There is no reliable estimate of financial losses associated with fraud within the federal government, said the report, but a 2016 global study by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners indicated that all kinds of organizations around the world suffer significant losses as a result of fraud.

All of Canada’s federal organizations are responsible for ensuring that their information, assets and integrity are safe. But within the 2013 to 2016 timeframe, auditors found that only the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Global Affairs Canada, and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada had actually completed a fraud risk assessment.

Even then, it said, some best practices elements were missing from those assessments.

Treasury Board providing adequate support

All organizations however, had governance structures in place that contributed to fraud risk management, including independent audit committees, values and integrity offices, and units to investigate fraud allegations. Some had additional structures, including an ombudsman or national centre for allegations and complaints.

Auditors reported that while their report did not try to specify individual cases of fraudulent activity, it did examine whether the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat had adequately supported and managed how the five organizations managed their overall risks.

Ferguson's office found that the secretariat fulfilled that requirement, but did not, as some other countries do, provide specific guidance about the risks of fraud themselves.

In the future, it recommended that the secretariat increase awareness of the importance of managing fraud risk within federal departments by supporting senior management with fraud risk assessment. It also suggested that it consider issuing guidance on how to manage such risks.

Comments