Kanaka Bar four steps ahead of climate change

Story and multimedia by Emilee Gilpin

The T'eqt''aqtn'mux (the crossing place people) come from T’eqt’’aqtn (the crossing place). Today, it's called Kanaka Bar. It was renamed after governor James Douglas declared the mainland colony of British Columbia.

Kanaka Indian Bar Band, located in the heart of the Fraser Canyon, is one of 15 Indigenous groups in the Nlaka'pamux Nation. During the Fraser Canyon War of 1857-1858, the Nlaka’pamux communities of the Fraser and Thompson rivers came together to “stop American manifest destiny,” explained Patrick Michell, elected chief of the T'eqt''aqtn'mux.

Kanaka Bar Indian Band is located off of Highway 1, three hours northeast of Vancouver, B.C., 14 kilometres south of the village of Lytton.

A small community that fluctuates between 70 and 140 members, depending on the season, Kanaka Bar's reputation has steadily grown with the success of numerous clean energy projects.

In 2013, in partnership with Innergex Renewable Energy Inc., Kanaka Bar opened the massive Kwoiek Creek run-of-river hydro plant. Success generated gains that the community has used to install solar panels, build a community garden and make sustainable plans for future generations.

These investments have helped equip Kanaka Bar for a future that will inevitably involve climate change chaos, says the chief.

"We realized nobody would save us"

Chief Patrick Michell woke up to more rain and clouds on a mid-January Sunday morning.

He drove down to the band office around 7 a.m. to prepare a pot of hot coffee before participants of a confined-space rescue course arrived. The band offered the course to Kanaka members, to have more employable hands on deck for current and future development projects. The course, taught by a trainer from Raven Rescue, teaches students how to handle emergency rescue situations in confined spaces, such as some of the working environments at the Kwoiek Creek run-of-river hydro facility.

Seated comfortably around the table, surrounded by diagrams and maps of their traditional territories, Chief Michell joked about stereotypes of Indigenous people in Canada who are often called "lazy and drunk."

"Here I am at the band office on a Sunday morning at 7 a.m. and haven't had a drink in years. And here you are too," he said, nodding to the two men who showed up on time. About a handful of participants had been invited for the class, and members of the group said it would take time to motivate more people to come out. As Chief Michell likes to note, change takes time, it's incremental, and even one person willing to step up makes a difference.

As the group waited on another participant, Chief Michell invited listeners to travel back through time. We have to look backwards, he explained, before we can understand where we are today and where we're headed tomorrow.

In 1978, Chief Michell said, life was dim.

“With over 150 years of settler government land and resource control, we experienced the harsh impacts of a boom and bust economy,” he said, briefly nodding to his nephew Dennis, who didn't need more of an explanation. "We all knew what was written for us. We wanted to drink, do drugs, fornicate, commit suicide. It was preordained. Life was shitty and we wanted someone to save us."

But then came a moment of clarity. “We realized, nobody would save us," Chief Michell continued. "Eight thousand years our people have been here and nobody ever saved us. We survived colonization. If we weren’t happy with the status quo, it was up to us to change it.”

On July 1, 1967, Canada celebrated its 100th birthday, a century after the British North America Act created the country we know today. It was also the day Chief Dan George of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation performed his famous soliloquy, A Lament for Confederation.

His address to about 32,000 people at Vancouver's Empire Stadium was broadcast live. He opened with, "How long have I known you Canada? 100 years? Yes. 100 years and many many more. Today when you celebrate your 100 years of Canada, I am sad, for all the Indian people throughout the land."

"He basically bannock-slaps all of Canada," Chief Michell joked. But his smile quickly faded to seriousness as he remembered hearing the lament for the first time. It changed the way he thought about things, he said.

"The last two paragraphs say, now you have survived colonization, rise up, get off the pity pot, learn their language, learn their laws and become a better person, family and community," Chief Michell paraphrased. "Yes bad things happen to good people, but we survived."

Though Chief Dan George and others gave him hope, the law didn't favour Indigenous Peoples until 1960, he said.

Chief Michell said he survived the years of residential school he was forced to attend, as well as the intergenerational dehumanizing effects it had on his family and Nation. When he came out, he said he could either drown in alcohol, drugs, or books.

He chose books.

Reading encyclopedias by candlelight, Chief Michell explored countries, cultures, places and people he would never actually meet. He grew up in a house with 17 people and no electricity, but he had everything he needed, he said.

His love of learning led him to the University of British Columbia, where he studied education and forestry. He left, worked in the service industry, got a two-year management degree from Douglas College and finally applied to the UBC School of Law.

He was called to the bar in February 1997, and practiced law in Lytton until March 2005. He spent a few years in the service industry, where he "recharged his batteries." In April 2008, Chief Michell was asked to take a position as Kanaka Bar's community liaison, to assist a partnership between the band and Innergex, the power company. In 2014, Chief Michell stayed on as Kanaka's Economic Development Officer.

In December 2015, when former Chief James Frank announced his retirement, Michell was elected to replace him in the first election the band had held in over 35 years.

Language is more than words

Woven into the fabric of every language are distinct ways of thinking, being and relating. As renowned Cree musician Buffy Sainte Marie has said, "Language and culture cannot be separated."

Take the verb "to know" or the concept of "knowing." In English, we have one verb for knowing, "to know." Some languages have more. In all of the Latin languages, for example, there are two ways to describe knowing. The knowing of a fact or definition, and another more intimate, long-term kind of knowing, of a place, person, emotion or experience.

Chief Michell said for the T'eqt'aqtn'mux, there's a difference between a definition and knowing. In school, he learned many definitions of things, facts he memorized, he said, but from his relatives and from the land, he learned how to know in an entirely different way.

“If you know your language, you know who you are," he said. "Words carry knowing. A lot of this knowing has been misplaced, but not lost. Timieux is defined as land. Once you learn the word, in our ways, you are taught the law of the land: respect, asking permission, doing things right, cleaning up.”

This kind of relational knowledge transfer is hard to replicate today, he admitted, for how can we practice a language, if it is not spoken? How can we practice Indigenous ways of being, thinking, and relating, if we are doing so with the language that colonized our ancestors? How can we receive the language spoken by our elders, when they were beaten into silence?

Chief Michell said his mother and grandmother were "not allowed to speak Indian" in residential school. He was proud that on their deathbeds, they both refused to speak English. For two women who were told "bad Indians speak Indian," they journeyed long enough to return to their Indigenous tongues. This gave him hope.

Chief Michell grew up on the land of his ancestors

As he speaks about T'eqt''aqtn'mux's earliest relatives, pit house villages (whose remains still sit across the river), fishing, hunting and preserving during long winters, one might think Chief has a superpower. He sees into the past and to the future. His historical knowledge of his Nation and his vision for the future are equally impressive.

As we stand in front of the band office, looking to mountains blanketed by trees, shades of green and frosty white, he tells me how the T'eqt''aqtn'mux used to cross from one side of the Fraser and Thompson rivers to the other.

Settlers described his people as nomadic, he said, because, according to his research, if they recognized the Indigenous peoples' relationships to place, they would have to acknowledge their pre-colonial laws and jurisdiction over their land and resources too.

"The T'eqt''aqtn'mux lived in our territories for 8,000 years," he explained. They fished off the river that fed them 11 months of the year, hunted, preserved, traded what they couldn’t provide themselves, practiced rich cultures and flourished, he said.

“Over the last 8,000 years, there were economies,” Chief Michell explained. The community used what was available and developed sophisticated trading systems with neighbouring nations and early settlers. “Simon Fraser arrived on June 20, 1808. He immediately noted that there were buffalo hide, steel, all this stuff that we had acquired through relationships with other nations, through trading.”

It’s not romantic, he said, it’s just the way it was. But would Chief Michell trade his denim for furs? Give up his cell phone, to go back to a time passed on through stories, from one generation to the next? No, he wouldn’t. But he sure won’t stay still either.

The first step to self-sufficiency, Chief Michell said, is awareness. It’s important to tell the stories of old, so that Kanaka members today know where they come from and who they come from, in order to understand how to walk forward in a good way.

"After awareness, comes implementation,” he said.

The Kwoiek Creek Project

Patrick Michell was elected chief in 2015. In the early stages of his tenure, he resisted federal recommendations for a comprehensive community engagement plan.

“No, we need a land use plan,” was the Chief’s response. “We have knowledge of the land and resources here. If you want to know about the land, go to the land. If you want to know what renewable energy project will work best, just ask the land.”

The land is broken and battered, Chief Michell said, but it also survived. Like Indigenous Peoples, it has changed and adapted. For 8,000 years, Kanaka lived sustainably off of the land and now the community is transitioning back to self sufficiency.

The idea for a renewable energy project arose in 1978, Chief Michell explained. The nation obtained a water license in 1990, an Electricity Purchase Agreement from B.C. Hydro in 2006, a certificate from the Environmental Assessment Office in 2009, and hired a CEO in 2013.

Kanaka’s corporate organization, Kwoiek Creek Resources Inc. owns 50 per cent of the Kwoiek (pronounced Kay-eek) Creek power project, located on the west side of the Fraser River. Innergex owns the other half of the project, but will release full ownership to the band in 36 years, as a part of their agreement.

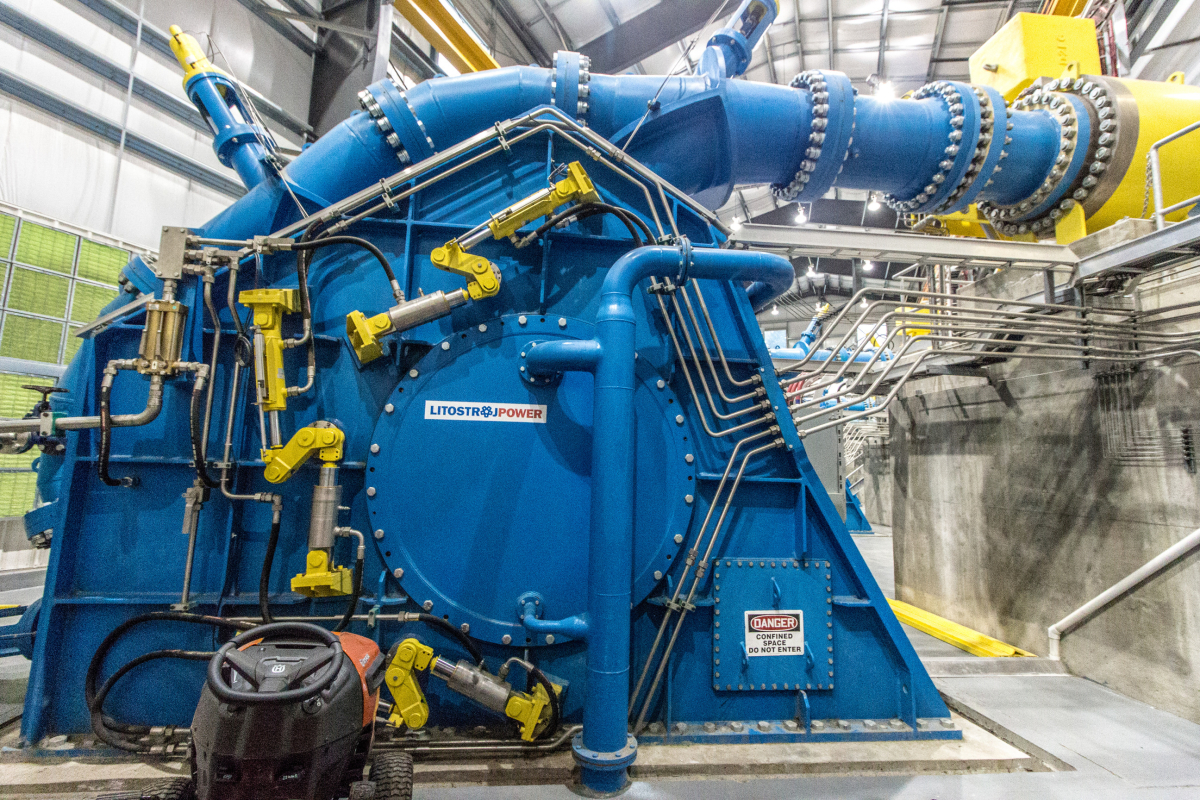

The run-of-river project produces approximately 215 GWh of electrical energy per year, enough electricity to fuel up to 22,000 homes.

Gary Handley, the hydro station manager, took me and the men from the confined-space rescue course down the massive gondola across the river to the power plant. When Chief Michell dropped me off, he told me with a mischievous sparkle in his eye, that the crossing people were invoking their old traditions, with a modern twist. Here they were, generations later, crossing the river again, but this time in a massive gondola.

The plant is a simple system, with a lot of updated technology. It’s basically a giant water wheel, just like the old days.

There are 15,000 metres between the source of the water and the power plant. The water drops through a penstock (or giant water slide), which is eight km long. The pipe is 1.9 meter in diameter. By the time it reaches the plant, it’s 800 pounds per square inch (psi) of pressure powering through a 1.9 meter pipe (for anyone unfamiliar with power pressure measurements, this information will fly by, but for the men attending the course, it was enough to gasp at).

“It’s a lot of pressure,” explained Handley, pointing to a screen in the operating office with an illustration of the system. “The water comes through these needles here, hits the runner, spins around, and there’s a generator on the other side of the turbine. The turbine drives the generator and the generator puts out 13,800 volts.”

A 72 km power line transforms 13,800 volts to 138,000 volts, from the Kwoiek Creek plant to the Mammott Lake substation.

If the plant needs to be shut down, due to ice or a fallen tree, it is done so slowly and with great care. Deflectors, acting like a jet boat in reverse, Handley explained, deflect the water away from the pipe. It can take about 36 hours to shut all generators down and 24 hours to start them up again. If it’s done any faster, fish will be stranded in the creek.

“The main focus here is not stealing the water from the fish, or killing the fish,” Handley said.

For backup, the plant relies on a diesel generator. The hydroelectric generator is basically the same thing, but bigger, and powered by water, rather than diesel.

“Patrick had the idea for the plant years ago, but he had to find someone to put the money in and make it a reality,” Handley said. “Innergex has the expertise, knowledge and money.”

But Chief Michell said Kanaka Bar offers the project a different kind of expertise. According to their Traditional Territory Land and Resources Strategy, the band respects strict rules when it comes to any project in their territories: do it right; take only what is needed; if you take it in, take it out; and return the land back to its natural state when finished. Chief Michell said the band will respect Indigenous protocol, T'eqt''aqtn'mux traditional cultural values, no matter what.

Before Michell was Chief and the Kwoiek Creek plant was built, the band head-hunted Zain Nayani

Forecasting the success of the power plant, the band knew they needed support to help manage finances. Nayani, current CEO for Economic and Business Development for Kanaka Bar, said when he first moved from Pakistan to Canada, to do an MBA at Simon Fraser University, he had no idea what he was getting himself into.

Nayani started as an intern, but was eventually hired by the band, he said while sipping tea in Jade Springs, one of the only restaurants in the town of Lytton. Nayani drives up to Kanaka Bar quite often. He used to stay in the closest hotel, in Lytton, but he's part of the family now and rents a room in the new subdivision built on the reserve.

Though he said he had a lot to learn about Canada's history of colonization and the current state of affairs for Indigenous Peoples, Nayani said he could relate in his own way. He was born and raised in a progressive Ismaili community in Pakistan and was taught from a young age how to love and live and how to help others do the same, he said.

Nayani said he came into the community at a really exciting time, when they brought back their membership and election code and wrote a modern code of community conduct within the governance code.

"We created a CEO because the community wanted to separate business from politics and decision-making from implementation," he explained. "By listening, we understood that people wanted a code of ethics and leaders who were open, honest, transparent and fair to people."

Nayani has worked with over 96 Indigenous communities on a project in collaboration with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. He said he's inspired by the steps Kanaka Bar has taken towards self sufficiency, steps that he doesn't see other nations taking. What makes Kanaka Bar stand out, he said, is the actions they took after their first successful project.

"The money from the first one or two successful projects should feed the community, not more projects that only create financial and economic returns," he said, reflecting on what he has learned from Kanaka Bar's model to success. "How do we define wealth? Is it just money, or is it an authority over land and resources?"

Success, as far as Nayani is concerned, is a strong community with a sustainable vision for the future, he said.

Climate change is inevitable

Kanaka Bar knows that climate change is real.

Part of the band’s regular council and community meetings focus on preparing the community for the environment and economies of tomorrow.

Some of the wins from the renewable energy sector fuel the band's housing program, food self-sufficiency project and solar project. They recently built a new subdivision, that rests just behind the semi-circle reservation, located on the east side of the Fraser River.

In May of 2016, Kanaka Bar started searching for a renewable energy company that would not only help install a grid-connected solar project, but one that was also able to train members and build capacity within the community. After reviewing different proposals, Kanaka Bar chose Riverside Energy Systems.

Ben Giudici, one of the directors of Riverside, worked closely with the Kanaka community in the summer of 2016. He said over the phone that their organization always attempts to go beyond installation. They believe in building relationships with the communities they work with, and helping members learn about renewable energy projects.

"It was inspiring for us to see Chief Patrick’s commitment to the project becoming a source of community pride," Giudici said. "Kanaka Bar Band demonstrated that small projects are possible. Many people think you have to do a big project that requires big capital investments, but that's not the case."

Kanaka hired Riverside Energy Systems to install two grid-connected solar projects, one at the band office and the other at the health centre. The community ran a “solar boot camp,” teaching Kanaka members about solar energy, installation and maintenance.

The shade-tolerant design uses 24 Canadian Solar 260 watt solar modules, with integrated solar optimizers, and a 7.6 kW Solar Edge optimized string inverter. The projected annual solar harvest for the first site is 6,300-6,600 kW/year, and 4,200-4,400kW/year for the second.

The second site, located just behind the health center, has red, black, yellow and red mounting poles. This is no accident. They represent different nationalities, Chief Michell explained.

Capacity building is essential for a community on their way to self-sufficiency. Not unlike other First Nations, they want to learn the skills they need, to foster self-determination efforts.

The cost of solar, Giudici said, has dropped in the past few years, while the cost of electricity has risen. People want to do their part to counter climate change, he added, and solar projects are a great step in the right direction.

The community has worked with Growing in Communities, a Canadian non-profit that works with First Nations communities around food self-sufficiency and The Urban Farmer, a permaculture mentor who helped who helped Kanaka develop the small community garden behind the band office. They also worked on land redevelopment plans with support from Urban Systems, an engineering consultant based out of Kamloops. Kanaka hopes to plant their own veggies and avoid buying imported produce from overpriced grocery stories.

While the projects “made at Kanaka, by Kanaka, for Kanaka,” might look like a mere hobby, they are aimed at establishing steps towards self-sustaining future generations.

Kanaka Bar residents have always observed climate change in their territories, from changes in temperature, declines in fish runs, precipitation irregularity, droughts, wildfires, all increasing in intensity, duration and frequency, Chief Michell explained. Now, they actively track the changes, both at home and abroad.

"When a state of emergency is declared, let's say in the United States, the federal government must send aid," Chief Michell said. "California, Puerto Rico, Louisiana, Florida. How long until the regional governments and the federal government go bankrupt? How much money am I going to get from a bankrupt federal government?"

"The time is now, to take preemptive measures. We cannot wait to deal with climate chaos," Chief Michell said. Look at recent earthquakes and tsunami warnings along the coast of Canada, he said. Are we ready?

He said Kanaka is making serious investments towards a sustainable future. With a small, yet diverse economy, Kanaka Bar is implementing a four-point strategy to achieve long-term community self-sufficiency in energy, food, employment and financial wellbeing. The last is expendable, Chief Michell says, and the others are non-negotiable.

Kanaka is creating a community climate change vulnerability assessment, a community water and watershed health plan, and land redevelopment plans. They are involved in a community catalyst program that provides Kanaka youth training in renewable energy project development. They are also planting seeds for a highway rest stop, where they hope to employ members and invite those passing by their home, to stop, take a look around and learn a thing or two about their culture and community.

"If you come to Kanaka and start pitching about project development, I'm going to ask you about life cycle," Chief Michell said. "What is your project's life cycle? How do you intend to comply with our conditions? How will you clean it up, make it sustainable and maximize safety?"

Rome wasn't built in a day, Chief Michell likes to say, but it didn't fall in a day either.

If you don't have a vision for a sustainable future, unlike those pushing pipelines through, he said, then you're behind, not ahead of the game. But Chief Michell isn't chief of every Nation, he's the chief of Kanaka Bar, and he will continue to rise, every morning, to proactively fight for the wellbeing of his children and their children.

That's worth living for, he said.

Editor's Note: First Nations Forward is being produced in collaboration with the Real Estate Foundation of BC, I-SEA, Vancouver Foundation, McConnell Foundation, Vancity, Catherine Donnelly Foundation, Willow Grove Foundation, and the Donner Canadian Foundation. National Observer retains full and final editorial control over the reporting process.