Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

From Duane Stone’s house, the air monitor looks like a tiny white dot on a chain-link fence. It’s so inconspicuous he’d never even noticed it. But since January, it’s been collecting data that underscores all is not better in Sarnia, Ont., one year after the provincial government vowed to “drive down emissions” in Chemical Valley - home to one of the largest petroleum and petrochemical complexes in Canada.

At that monitor, which is strapped to the fence of the Shell refinery and fewer than 100 metres from Stone’s house, the amount of benzene, a cancer-causing chemical, reached 23 times Ontario’s daily air quality level, earlier this year. That provincial level, while not legally binding, was created to protect people’s health.

Stone had no idea.

“It’s upsetting because benzene is a dangerous substance,” Stone said when Global News showed him the data. “They shouldn’t be that high here. I mean, I don’t even know how high they are right here at this door.”

Last October, a Global News investigation, in partnership with the Toronto Star and National Observer, exposed a pattern of industrial leaks and spills in Sarnia, with no alerts from the city and few consequences for the companies. But one year later, little has changed.

'Just shut your doors and your windows and shut off your air conditioning'

Across the street from Stone's house, the highest benzene reading lasted for two weeks while elevated levels continued for four more.

“We quickly identified the source of the elevated readings as a faulty seal on a storage tank that allowed vapours into the atmosphere,” said Tara Lemay, spokesperson for Shell Canada. “ We implemented a program to resolve the issue and these steps are working as the data shows a decline in benzene readings.”

Shell says it reached out to Aamjiwnaang First Nation as well as the Bluewater Community Advisory Panel to discuss what was being done to address the elevated readings.

“I think it’s a disgrace and the plant should be fined,” said Pamela Williams, who also lives across the street from the plant.

Williams says just last month there was a benzene scare from one of the nearby plants.

“They just tell us ... to just shut your doors and your windows and shut off your air conditioning.”

But while the data may be disturbing to some, it’s also a sign of progress.

In July 2017, five companies that said they couldn’t meet Ontario’s stringent benzene standard were approved instead for an alternative process, called a “technical standard.” Under a technical standard, companies are not breaking the law if they don’t meet the benzene standard - but are required to make progressive technical modifications, including greater leak detection and repair.

By January 2018, they were required to have air monitors installed at their property lines to see how much benzene might be seeping into the public’s breathing space - and report it on their websites. The monitors are able to collect data that wasn’t previously available, filling in the gaps as to what’s in the air. It’s data that the government’s air monitors, several kilometres apart, aren’t picking up.

The data is crucial new information for the people of Aamjiwnaang First Nation, who are arguably the most impacted by the emissions. The community of 900 residents lies right in the middle of the industrial complex. Shell Canada sits to the south, Suncor Energy to the west, Nova Chemicals to the east and Imperial Oil to the north. And some residents live mere steps from the plants.

“For the majority of monitors, the benzene concentration, two-week results are below guidelines set to be protective of human health for short-term (one to 14 days) exposure,” said Gary Wheeler, spokesperson for Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment.

But not all readings were within that protective range.

Across the street from Aamjiwnaang’s ball field, an air monitor for INEOS Styrolution, a chemical manufacturer, registered benzene readings that, for nine months, averaged 12 times Ontario’s desirable daily level.

“It certainly means an elevated risk,” said Dr. Tim Takaro, a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University. “Kids will be playing on these ball fields. I would want to know what the exposures are in the outfield.”

“The point that they are sustained, that is very important of course.”

Leaks and spills still common in Aamjiwnaang First Nation

Despite expressing “concern” over some of the elevated levels, Lee Orphan, director of the Southwest Region of the Ministry of the Environment says, “this is again a success story.”

The high readings at INEOS flagged an issue.

“The company in the short term has fixed the gaps... to prevent some of the benzene from releasing,” said Orphan. He says it will be putting a permanent solution in place by January of next year.

But that wasn’t the only incident at INEOS.

Sometime between late May and early June 2018, the amount of benzene at air monitoring station 10 on the southwest side of the plant reached a level above 1,000 micrograms per cubic metre — a reading so high, it hit the detection limit. The daily level for health protection is 2.3 micrograms per cubic metre.

“The elevated value was caused by the cleaning of a storage tank” and was “an isolated incident,” said INEOS’ site director, Brian Lucas. INEOS notified the Ministry of the Environment. “At no point in time was there any danger to people in the neighbourhood of the plant,” Lucas said.

But neighbours in Sarnia and Aamjiwnaang First Nation weren’t notified.

A Global News analysis of all industrial alerts sent out by the Aamjiwnaang First Nation in the past year has revealed leaks and spills are still common. Nearly once a week on average, the Aamjiwnaang First Nation receives and then warns the community about a leak or a spill. Warnings of increased odours come at the same rate. Noise alerts are weekly on average and warnings about large flames shooting out of the plant stacks happen on average twice a week. And while most of these events are relatively minor, some neighbours are worried about the combined effect these chemical releases have on their health.

“They don’t seem to realize, that the reserve, we’re all human beings,” Williams said.

And then, there are the not-so-minor events.

Like the night of Thursday, March 15, 2018.

It was 8:10 p.m. when the first in a string of calls started flooding the government’s Spills Action Centre.

The next came at 8:30 p.m.

Then 8:51 p.m., 9:12 p.m., 9:25 p.m.

By 10:46 p.m., 11 people had called complaining of a range of symptoms from difficulty breathing, to burning eyes, nausea, headaches and a strong rotten egg odour.

An air quality sample collected by the Ministry of the Environment detected elevated levels of hydrogen sulphide downwind of the Suncor refinery.

“The Suncor Sarnia refinery experienced a steam generation tube failure in a plant heater that led to the shutdown of several operating units,” said Nicole Fisher, spokesperson for Suncor. “As per our operating practice, material from the affected units was temporarily sent to storage tanks….Field checks by site personnel determined storage tanks were the most likely source of the odour.”

Suncor apologized for any impact this had on the community and said it notified Aamjiwnaang First Nation and the Ministry of the Environment, which is now investigating the hydrogen sulphide emissions.

Hydrogen sulphide, which can cause headaches, dizziness and nausea at low levels, can be deadly at the highest concentrations. Benzene, by contrast, is linked to leukemia and is labelled a class-1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

In Lambton County, which includes Sarnia as well as many other communities to the south and east, statistics do not suggest a higher occurrence of leukemia and blood cancer than the rest of Ontario.

By contrast, the city of Sarnia, including Aamjiwnaang, reports more hospital admissions for respiratory illnesses than nearby Windsor and London.

“The people of Sarnia (and) the people of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation deserve to understand, what, if any, health impacts this has had,” said Ontario’s Environment Minister Rod Phillips, who has committed to following through with a health study that was promised by the previous Liberal government, following the Global News joint investigation one year ago.

While the previous environment minister, Chris Ballard, rose in the legislature to promise the study last October, Phillips said that when he took over, he discovered no money had actually been put aside for it.

“What we found is that as much as it had been talked about, it hadn't been funded and it hadn't been acted on,” Phillips said.

The money has now been allocated, and a multi-million-dollar, multi-year study to determine whether the emissions are making people sick is now guaranteed, Phillips said.

“It is crazy to me that for 10 years we've avoided answering that question. But we will now.”

Progress is also being made in other areas. Sarnians can now access real-time air monitoring data on the Clean Air Sarnia and Area website, which launched in February — and a 40-year-old sulphur dioxide air standard was updated in October 2017.

But it’s whether these emissions are affecting people’s health - that’s at the root of the concern.

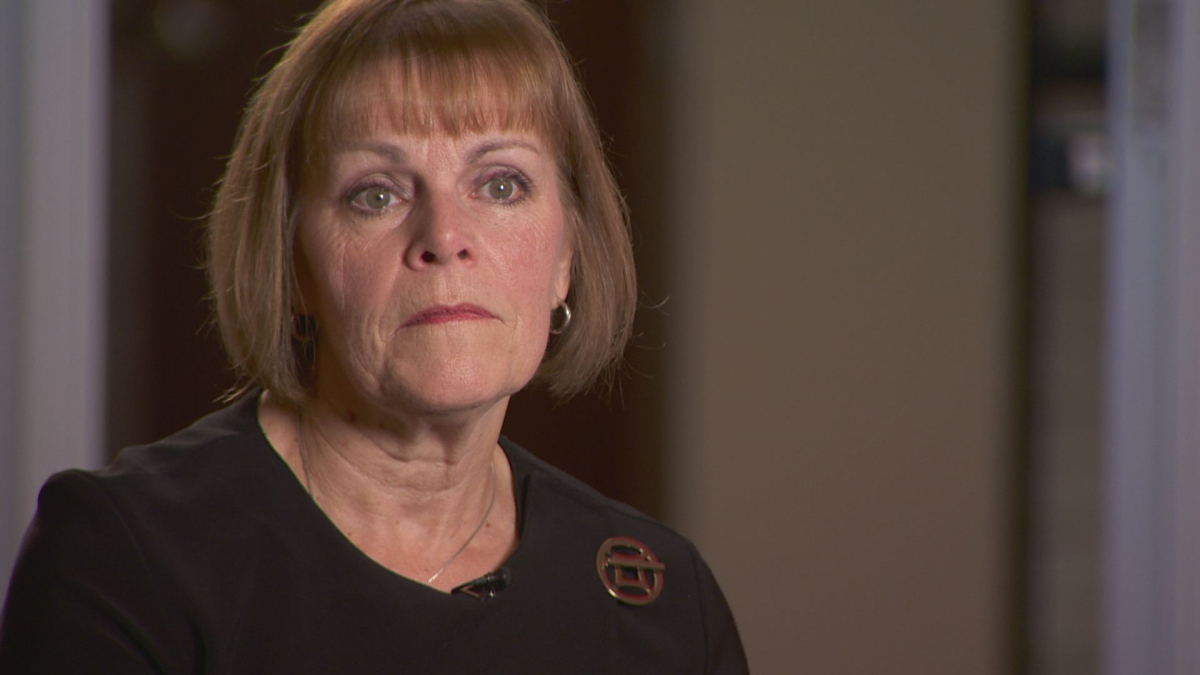

Anne Marie Gillis, chair of Lambton Community Health Study Board, which had been advocating for a health study for more a decade, says that while emissions may not be severe as 20 or 30 years ago, today’s concerns “can’t be sloughed off.”

“It’s not just the health of the community, it’s the anxiety that is surrounding the health of the community. Are we being unduly exposed? What are the risks of being exposed?”

Phillips, whose first official trip as environment minister was to Sarnia, says enforcement on industry will be tough. When asked what a reasonable length of time might be for the people of Aamjiwnaang and Sarnia — who have heard similar promises before — to expect change, he said: “If I were them, I would think, ‘yesterday.’”

“People just want to hear that someone's going to take responsibility, starting with making sure the study gets done, making sure that the monitoring and the enforcement is happening. That's the responsibility that we’ll take.”

Comments

Everywhere the oil/gas, petrochemical, pharmaceutical and extractive industries operate they create toxicity - through spills, emissions, deliberate dumping, both "legal" and illegal.

Their entire business model, their "prosperity" depends on these practices being committed with impunity, without meaningful fines, or the investment required to end the toxic releases (if that is even possible).

Governments - everywhere in the world, have mostly failed to end, or even reduce the poisoning of the planet.

We make gains - for a while, in cleaning the air, or the water, and then someone comes along with new policies, or old policies, and things plunge backwards - as they are now doing under the regimes of the climate deniers, the captured oil/gas apologists, and so the see-saw continues while the planet burns.