Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This story was originally published by High Country News and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

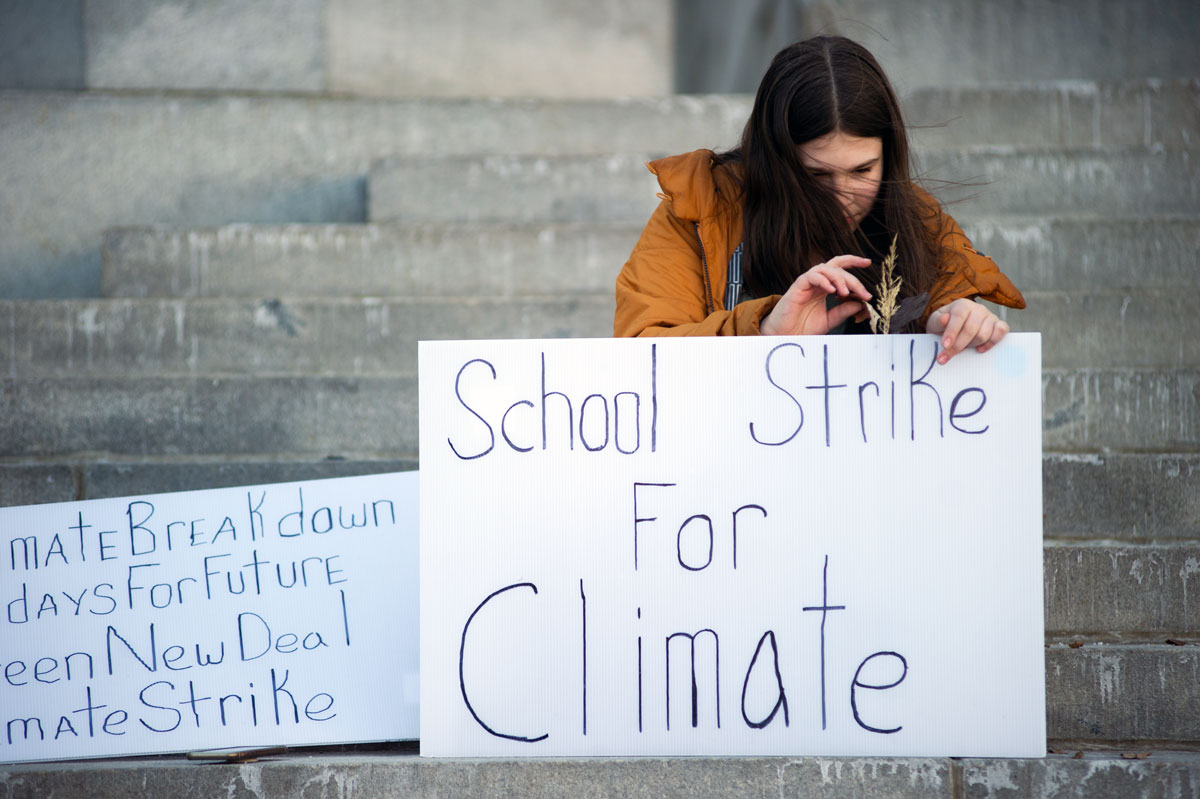

Every Friday since the beginning of this year, bundled in a burnt-orange puffy jacket, 12-year-old Haven Coleman has protested climate change in front of government buildings and businesses storefronts in Denver, Colorado. The reactions are mixed. Last week, a man flipped her off through his rolled-down window; other times, people shout words of encouragement or give a thumbs-up. At one of her strikes in February, I find her sitting cross-legged on the cold, hard cement steps leading to the entrance of the Denver City Council building, two posters propped up next to her. One sign has four hash-tagged words: #ClimateBreakdown #FridaysforFuture, #ClimateStrike and #GreenNewDeal written in large skinny black letters. The other proclaims: “School Strike for Climate.”

After about half an hour, an older gentleman in a neon-yellow T-shirt and worn blue jeans pauses to read Coleman’s signs. He doesn’t like what they say. “That’s to your disadvantage,” he tells her matter-of-factly. “You need school.” Coleman, a seventh-grader with long brown hair and expressive hand gestures, tries to come up with a quick response, but by the time she’s pulled her thoughts together, he’s already gone up the City Hall steps.

Around the country, other young climate activists have gone on similar solo strikes, cheering each other on from afar through Instagram and Twitter. They find encouragement from teens in other countries, like England and Belgium, where the youth climate movement has inspired a vast wave of students to ditch class on Fridays and flood into the streets to protest. Like many adults, they are energized by the eloquent, powerful and at times frightening speeches of Swedish 16-year-old Greta Thunberg, who has been protesting in front of the Swedish Parliament since last August.

With a future that looks increasingly perilous — a recent U.N. climate report gave world leaders just 12 years to act to avoid the worst effects of climate change — Coleman and her peers feel a sense of urgency. “Us kids, we are the only ones who are doing anything recognizing that our future is at stake,” Coleman said, with a hint of exasperation in her voice. “The reason why we are ‘climate striking’ is to try and get the attention of the adults, because we can’t vote — but we can influence senators.”

And grabbing the attention of adults is Coleman’s strong suit. She made headlines over a year ago, when she spoke at a town hall hosted in August 2017 by Republican Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner, who has received over $1.2 million dollars in campaign funding from oil and gas industries. The senator listened to Coleman’s heartfelt speech that day from the stage. Through tears, she pleaded with him to take action against climate change. She even offered to help. “If the carbon polluters’ money is holding you back, I can organize kids, adults and money and we can use social media and do grassroots,” she told him, as people in the crowd flashed green cards and cheered.

Gardner didn’t take her up on her offer, but the videos that surfaced of Haven’s speeches to Republican State Rep. Doug Lamborn, a known climate change denier, garnered the attention of another prominent figure, Al Gore. She had met him briefly once before at a training event. But months later, after hearing about her climate activism in Colorado, he invited her to be a part of his “24 Hours of Reality” project, a day of television programming centered on climate change. Coleman says her activism “has been going up from there.”

These days, all of her energy is going into planning the U.S. Youth Climate Strike, a national event organized by Coleman and two other young climate activists, Alexandria Villasenor and Isra Hirsi. It will take place in solidarity with a global school strike for climate action on the same day, in which students plan to urge U.S. politicians to adopt the Green New Deal and to stem the effects of the “climate crisis.” Over 300 people have already signed on to lead strikes in their cities. With less than a month to go, events have been confirmed in 28 states. Coleman is confident that the movement will reach every part of the country.

Balancing school and planning a national strike can be challenging — to say the least — for a seventh-grader. She caught some flak from a teacher when she missed a math-tutoring session; she’d gotten stranded on a planning phone call with her climate strike co-leaders. When she tried to explain that she had just started the U.S. version of a European climate action movement, her teacher responded by telling her, “You better get your priorities together.” Coleman has missed several days of school to attend rallies in D.C. and speak at climate change events, but for the most part, she tries to balance school with her activism. On her Friday strikes, she squeezes in her protests early in the mornings or during lunch, though sometimes she ends up a little late for her classes.

School and activism have never harmonized for Coleman, anyway. When she lived in politically conservative Colorado Springs, she says the other kids “hated my guts” and shoved her into lockers. “It got pretty intense, and I ended up doing home school.” At her current school in Denver, she says her classmates don’t really get this “climate activism thing,” so she tries not to bring it up too often. “It is just hard because when people don’t really understand… It is sort of like I’m hunting for dragons or something,” she says.

It’s difficult not having people her age to turn to when she feels overwhelmed by climate change, Coleman said. “When you are dealing with such a heavy issue at such a young age, sometimes it just brings you down,” she says. In those moments, her parents help her through it —especially because “you don’t see a lot of kids being activists.” The strike on March 15 just might change that. “I hope that a ton of kids will flood into the streets,” Coleman says.

At one point, I ask Haven what motivates her to turn her feelings about climate change into real action, something many adults have failed to do. “I feel like I need to do something,” she says, “because why wouldn’t you want to save your future?”

“We can stop the worst effects, so why shouldn’t I try and save all you adults?”

Comments

This is what some of us have been saying since the Kyoto protocol - we must reduce fossil fuel emissions for the future of our children and grandchildren and their children. And after twenty years our business and government leaders are still weak and greedy. Our future lies in the hands of a 12 year old and a 16 year old. This is the state of our world. We need to do better and support their beliefs and actions.

I'm not that young, but at the rate we're going I'm still going to be solidly alive when things get bad. Of course even if the timetable were slower it would be vile to inflict the results on our kids, but as things stand it's just moronic that we're fiddling while the planet starts to burn.

I have a lot of respect for a young person who feels strongly enough about an issue to 'take on the world'. I hope her teachers and tutor cut her some slack and adjusted their timetables to make scholastic ends meet.