Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Though Teck Resources’ decision to shelve its controversial proposal for a massive new oilsands mine triggered concern from some sectors of the business community, others say the project was doomed from the start.

“It’s finance 101: it’s way too risky” said Kathy Hipple, a financial analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, in an interview with National Observer.

Though Hipple said “it’s a tough decision for a company to have to make,” it didn’t come as a surprise to her.

“The company was in no financial position to pursue this,” she said, and the “project was becoming increasingly less viable.”

The Frontier mine, which was expected to cost $20.6 billion to build, would have been one of the largest oilsands projects ever developed in Alberta.

Teck Resources CEO Don Lindsay announced the company’s decision to pull out of the regulatory process just days before the federal government was expected to issue a decision on Frontier.

In a letter to Environment and Climate Change Canada Minister Jonathan Wilkinson, he pointed to unresolved issues in Canada related to resource development and climate action, suggesting that politics at least partially triggered the withdrawal.

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney said in a statement Sunday that “Teck’s decision is disappointing, but in light of the events of the last few weeks it is not surprising.”

The move comes after weeks of protests and blockades over a natural gas pipeline in northern British Columbia that brought issues of Indigenous rights and resource development into sharp focus across the country.

The decision whether to approve or reject Teck Frontier, meanwhile, had become a test — like the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion before it — of the Trudeau government’s seemingly conflicting commitments to climate action on one hand and support for Alberta’s struggling economy on the other.

It was against this backdrop that some observers saw the proposed mine as a symbolic lightning rod for the debate between climate and economy. Even if the federal government had approved the project, there would have still been questions about its economic feasibility, given low oil prices, lack of pipeline capacity, and growing number of financial institutions shifting investments out of the oilsands.

Teck CEO Don Lindsay also addressed the reality of that heated debate in his letter to Wilkinson on Sunday.

“Global capital markets are changing rapidly and investors and customers are increasingly looking for jurisdictions to have a framework in place that reconciles resource development and climate change, in order to produce the cleanest possible products.

“This does not yet exist here today and, unfortunately, the growing debate around this issue has placed Frontier and our company squarely at the nexus of much broader issues that need to be resolved,” he said. “In that context, it is now evident that there is no constructive path forward for the project.”

Lindsay added, however, that the company had confirmed the Frontier project is “commercially viable.”

It was expected to create thousands of jobs in northern Alberta and cause significant — and in some cases irreversible — harm to an area more than twice the size of Vancouver.

But it was the projected 4.1 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year that set off alarm bells for those concerned about the climate crisis.

Nevertheless, the joint federal-provincial review panel concluded last summer that the economic benefits of the project outweighed the expected environmental impacts.

Still, Teck’s decision came as a surprise to some, especially after the company said Friday that it would take a $1.1-billion hit if the federal government rejected the project.

Richard Masson, a fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, who has extensive experience in the development of oilsands projects, said it’s “stunning that they pulled away at this late hour” and it doesn’t bode well for Canada’s resource industries.

“It sends a very, very strong and negative message about investment in Canada's resource sector,” he said.

Masson said he “firmly believes” that the project had the potential to one day be economically viable, given ongoing improvements to cost structures and technology.

“To not even get that approval, you know, that really says they just didn't see any kind of future for it and ... not because of the economics, I think, but more because of the politics around all of this,” he said.

“When you have uncertainty around whether the government’s going to be supportive, whether the people of the country are going to be supportive, you raise the level of risk for a company making a decision, and they have lots of places in the world to put their capital,” he explained.

Economic Viability

But the feasibility of such a massive undertaking in the oilsands, where producers have been struggling through low oil prices and limited pipeline access, was in question and always subject of a heated debate.

Lindsay himself said during an investor call Friday that the company would consider leaving the oilsands business altogether if the fortunes of its existing Fort Hills project don’t improve within the next couple years. The company took a $910-million after-tax loss on the project during the fourth quarter of 2019.

Laura Lau, the senior vice president and chief investment officer with the firm Brompton Funds, said by withdrawing, Teck protects their ability to re-submit their application for Frontier again if the economic or political climate improves.

At some point, there may be a shift in government, the oil price may rise, and there may be more pipeline access, she said.

Last week, Lau said Teck needed at least three things for Frontier to be economically viable: pipelines, higher oil prices and a partner.

The company’s submitted economic analysis was based on a $95 US per barrel price for Western Texas Intermediate crude, a benchmark oil price, with low- and high- price scenarios ranging from $76.51 US to $115 US per barrel.

But oil prices have been significantly lower over the last few years, with WTI prices averaging $65 US per barrel in 2018, $57 per barrel in 2019, and $55 a barrel in 2020, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

In its fourth-quarter financial update, Teck made the point that the economics submitted as part of the regulatory process didn’t reflect the company’s “subsequent efforts to optimize the project.”

While some industry analysts including Masson agree costs for oilsands projects have improved, Teck was facing other challenges as well.

Finding a partner could be challenging, said Lau, not only because of low oil prices, but also because of the number of international players that have left the oilsands.

“There are fewer and fewer partners available,” she said.

Toby Heaps, the CEO of Corporate Knights, a media and financial information company that provides corporate sustainability rankings, said last week that Teck could also have had trouble financing the project given the growing focus on sustainable investments.

“There is a real chill, that cannot be ignored, that the entire oil sector is aware of with respect to global investor appetite to dedicate capital to them,” he said. “And the snowball is picking up steam.

“The reality is, people with the kind of money this project requires are not comfortable with the idea of throwing $20 billion down an expensive oil hole in a lower-forever oil-price world that's rapidly being disrupted.”

Ultimately, Teck Frontier may not have been able to compete with expansions of existing oilsands projects, which tend to be more economically attractive, Masson said in an interview last week.

And “that could be one of the reasons why Teck might say, ‘Well, geez, I better just hang off on producing a mine for awhile,’” he said.

But there was also the political uncertainty surrounding the Frontier project that Teck CEO Lindsay pointed to in Sunday’s letter to Wilkinson.

“The promise of Canada’s potential will not be realized until governments can reach agreement around how climate policy considerations will be addressed in the context of future responsible energy sector development,” he wrote. “Without clarity on this critical question, the situation that has faced Frontier will be faced by future projects and it will be very difficult to attract future investment, either domestic or foreign.”

In a joint statement issued Sunday, Wilkinson and Natural Resources Minister Seamus O’Regan seemed to push back, saying, “Our government is committed to developing our natural resources sustainably and to creating good, middle class jobs.

“As Teck has rightly pointed out, and as many in the industry know, global investors and consumers are increasingly looking for the cleanest products available and sustainable resource development.

“Canada will stay competitive in the global economy if our industries continue innovating with the best technologies in the world and if governments work together on a serious plan to protect the environment.”

Meanwhile, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney said the “news deepens our government’s resolve to use every tool available to fight for greater control and autonomy for Alberta within Canada, including reinforcing our constitutional right to develop our natural resources, ensuring a sustainable future for our oil and gas industries and restoring Canada’s reputation as a reliable place to do business,” he said.

Climate Costs

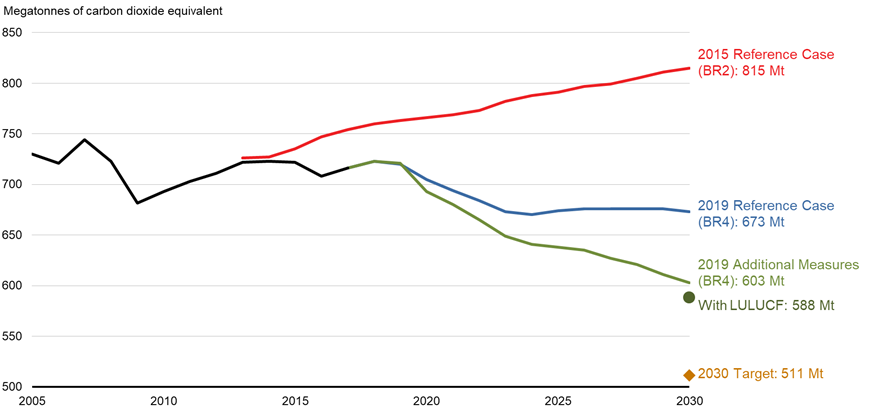

There is concern, though, that continued expansion of the oilsands will only make it more difficult for Canada to meet its climate targets.

Scientists have warned that the world has until 2030 to slash global greenhouse gas emissions in order to avoid some of the worst effects of climate change, which already contributes to devastating wildfires, droughts and floods.

At this point, Canada is facing a major shortfall in meeting its 2030 targets. Current projections show the country needs to cut another 77 million tonnes over the next 10 years — the equivalent of almost 19 Frontier-sized projects — in order to hit its target.

While Kenney had said earlier this month that, even with the additional 4.1 million tonnes of greenhouse gasses expected each year from Frontier, oilsands emissions would fall below Alberta’s legislated cap of 100 million tonnes a year for the sector. Federal figures suggest otherwise.

Estimates submitted to the United Nations show oilsands emissions reaching 86.5 million tonnes this year, according to a letter federal Environment Minister Wilkinson wrote to his provincial counterpart this month.

“Given there are approximately 2.7 million barrels per day of oil sands growth planned or under construction, there is significant risk that Alberta’s cap on emissions will be exceeded in 2030,” Wilkinson wrote.

The big question moving forward is “how are we going to manage emissions from the oilsands in a way that’s consistent with Canada meeting its international targets,” said Chris Severson-Baker, the Alberta regional director at the Pembina Institute.

It’s a discussion that’s critical for both the environment, the economy -- and many investors who hold stock in companies like Teck Resources Ltd.

Comments

It had to have been purely based on business. I'm pretty sure the federal government was hungry for carbon tax revenue, and being an Alberta project, I saw no reason for the BC government to intervene as long as the project is contained entirely in Alberta (possibly in northeast BC and Saskatchewan too). The only issue in BC would be if a pipeline to Vancouver was involved.

"The only issue in BC would be if a pipeline to Vancouver was involved."

It seems to me that Teck Frontier and TMX were hand-in-glove.

Can TMX keep full without Teck Frontier? I know I've heard Teck folk saying the Frontier mine couldn't make money without TMX.

The whole thing is a house of cards. It looks like the Wet'suwet'en have pulled a card out somewhere near the base, and the entire fossil sunlight industry is trembling, and maybe about to fall down.