Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

An advocate is demanding answers after the suicide of a young Indigenous inmate in Saskatchewan on Monday.

“He was crying out for help,” said Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) national vice-chief Kim Beaudin.

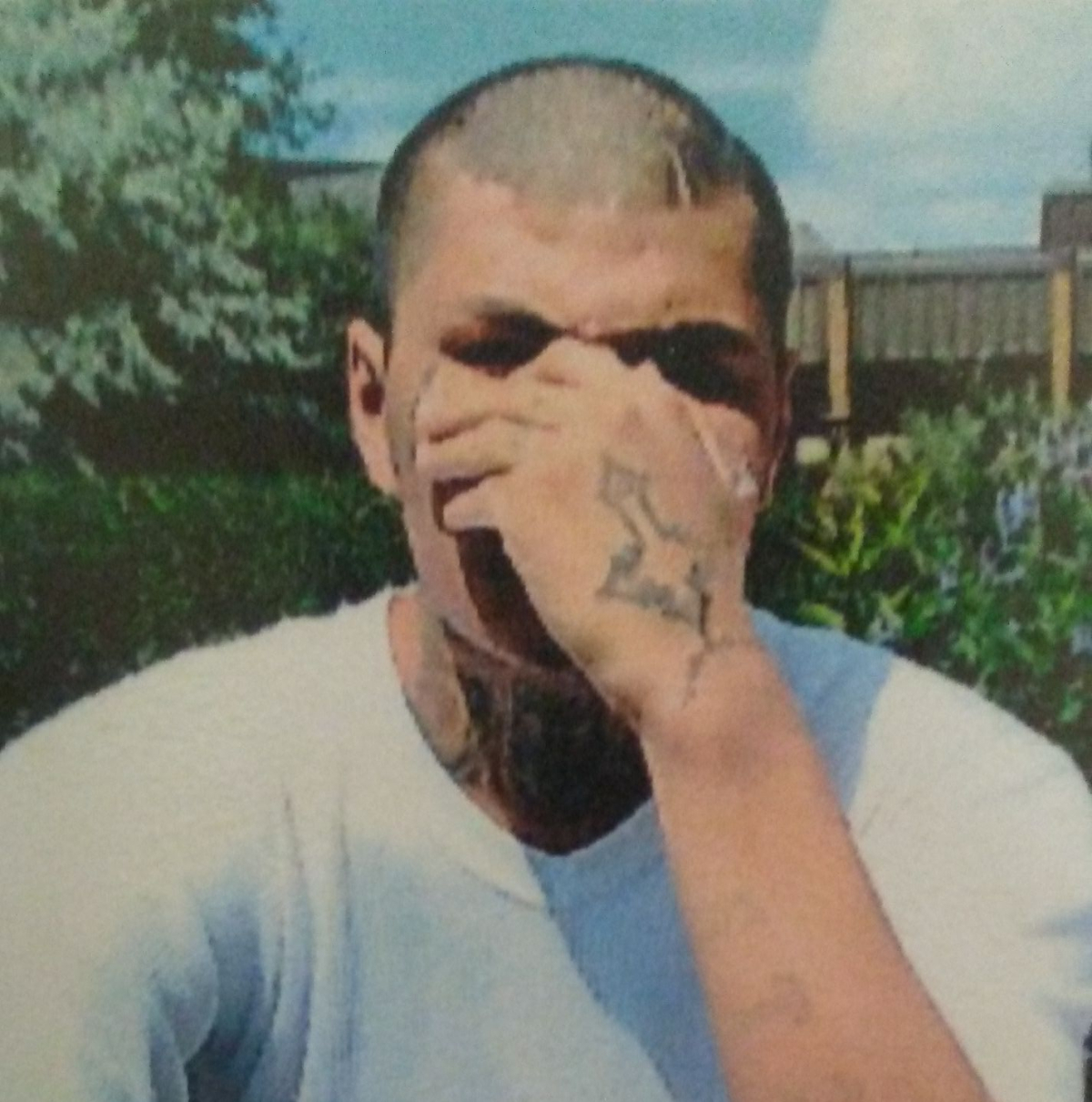

Curtis McKenzie, a 27-year-old member of Lac La Ronge First Nation Indian Band, took his own life Monday while in the custody of Correctional Services Canada (CSC) at Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert. CAP is calling for an inquest into McKenzie’s death, to be completed by the Saskatchewan Coroners Service.

“When he was in there, he was already displaying suicidal tendencies,” Beaudin said. “For example, he was cutting his arms with razor blades. I’m not sure how he got his hands on these razor blades. We want to make sure that the true story is being told.”

Beaudin said he was in Edmonton when the next of kin informed him McKenzie was found to be brain-dead and taken off life support after he hanged himself.

“I want to know how he got to that point. ... How did he get there if they knew something was wrong? Why didn't they figure that out? Why didn’t they help him out?” Beaudin said.

“They found him and they took him to the hospital in Prince Albert. … He was effectively a vegetable,” said Beaudin, who knew McKenzie personally through his time as an outreach worker in Saskatoon. “I knew he had issues around addiction, and we kept asking the probation officer and correctional services to send him to a treatment centre. But they wouldn’t do it. They would not do it.”

Beaudin said he was shocked when he got the news of McKenzie’s death. Until then he had high hopes for the young man’s recovery.

“But I knew that he would struggle when he was in there. Maybe at some point along the line he just sort of gave up,” he said.

McKenzie went through the foster care system as a child where he was abused, according to documents from the parole board. He had been in-and out-of prison on a range of charges.

Beaudin said McKenzie was dealing with alcohol and drug issues. He said while McKenzie was in and out of jail over the years, he had made the decision to stop associating with gangs and was working to improve his life.

“He was a good guy. He was very soft spoken. … He was a really good person and that’s why it was so disturbing to me what happened to him in there,” Beaudin said.

When he died, McKenzie was serving a two-year-plus-one-day jail term for breach of recognizance and breaking and entering, according to CSC. The sentence started May 30, 2018, and he was expected to be released in a matter of months.

Beaudin places the blame for McKenzie’s death squarely on the prison system; he believes that if McKenzie had been allowed to be with his community, where there was support, he would have lived.

“He’d be alive today — I know that,” Beaudin said. “We would have done everything we could to get him into treatment. … He needed to be in that process to really help him out. [Correctional services] just had no interest in him. … Leading up to [the suicide], they just didn’t do anything about it. They could have easily taken him to the hospital in Saskatoon, but they chose not to.”

Beaudin said McKenzie told him stories about mistreatment by staff while in solitary confinement during a prior stay at the Prince Albert penitentiary

“He was telling me that the guards would bug him all the time, and they would tell him that they put stuff in his food so he wouldn’t eat his food,” he said.

It wasn’t the first time McKenzie tried to injure himself. While in solitary confinement on another charge at the same penitentiary, he cut off his own nose with a razor blade allegedly provided to him by staff at the facility.

Beaudin, who worked as a justice of the peace for the Province of Saskatchewan for five years, said that McKenzie’s stint in solitary was the tipping point for the young man.

“He was telling me that he couldn't handle it,” Beaudin said. “He said, ‘Well, I’m gonna cut off my nose.’ So they gave him a razor blade and they said, ‘Go ahead.’ So he cut off his nose and shoved it down the toilet.”

CSC would not confirm the details above.

He expressed suicidal intent on a number of occasions, according to Beaudin. In 2017 McKenzie was on parole when he jumped into the Saskatchewan River while high on methamphetamines and assaulted a police officer as he was being rescued.

He told the court afterward that he did not remember how he got in the river.

According to Beaudin McKenzie was released to a halfway house only to be reincarcerated in 2018 after breaking the conditions of his peace bond.

Beaudin thinks the conditions of the peace bond were unfair to include abstention from alcohol and drugs to which McKenzie was addicted.

“You’re asking somebody to fail.“

“They offered no assistance and no resources and no support for him to do that. And so he ended up going back again for a year again. He got out again and he ran into the same problem,” said Beaudin.

Beaudin said that while officers kept Mckenzie under 24-hour supervision at the hospital, they didn’t have the same diligence while he was locked up.

“A guy tries to commit suicide and they can’t even watch him. But they can watch him while he’s laying in his deathbed. Oh my god. It’s stunning!” Beaudin said.

Beaudin said McKenzie was unable to handle the pressure of being in prison — especially solitary confinement. It is unclear whether McKenzie was in solitary at the time of his suicide.

Beaudin said McKenzie believed he had a legal case against corrections services Canada about “what happened to him when he cut off his nose.”

“There’s no way you should have access to blades … when you're in prison. Especially when you’re suicidal. It makes no sense to me and I have a feeling that we’re gonna find out more,” Beaudin said.

Citing privacy legislation, a spokesperson for CSC told National Observer that they cannot comment on any specifics.

“As in all cases involving the death of an inmate, Correctional Service Canada (CSC) will review the circumstances,” CSC said in its media release.

The federal inmate population increased 1.2 per cent since 2010, while the Indigenous inmate population increased by 52.1 per cent.

The rate of Indigenous incarceration within provincial correctional facilities in Saskatchewan is 76 per cent and is 65 per cent at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary.

According to the most recent national data available from the annual report of the office of the correctional investigator (2018-2019), “Indigenous offenders are over-represented in the number of incidents of attempted suicide, accounting for 39% of all such incidents in the last 10 years.”

“Correctional Services Canada loves the idea of change, but not the process,” Beaudin said. “Report after report seems to fall on deaf ears within government.”

Michael Bramadat-Willcock/Local Journalism Initiative/Canada's National Observer

If you are or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts, help is available at all hours. Support can be found at the Canada Suicide Prevention Service website. If you are in immediate danger, you can call 911.

You can learn more about suicide prevention in the province at Saskatchewan.ca.

Comments

It has been known, since the time of Columbus and the conquistadores that the natives of North America cannot be enslaved. They died in droves when captured/forced to work - most likely from European diseases as much as from European enslavement/incarceration.

This failure to "thrive" in captivity is why the importation of Africans to become slaves in north and south american plantations, mines and other forced labour took hold. Africans were more "resilient" !

European/White settlers/colonials were encouraged by their religions and by their economic greed, to render people of colour as non-/sub human, naturally inferior, and thus suitable for enslavement. It seems nothing has changed and the white male dominated incarceral personnel still feel, or become conditioned to, the mind set that requires them to abuse, in every way they can, the prisoners at their mercy. Mercy, there is none.

If a guard tries to treat prisoners as humans, other guards will abuse him/her in order to protect their own malfeasance. It is a death spiral with only one outcome.

The white superiority mindset, coupled with the crime of mass/excessive incarceration is inevitably a powder keg.